PET imaging with fluorine-18 dihydroxyphenylalanine (DOPA) can be an accurate means of diagnosing Parkinson's disease and distinguishing it from other neurological conditions, according to research presented earlier this month at the Society of Nuclear Medicine meeting in San Antonio.

Parkinson's disease affects approximately 1 million people in the U.S. and more than 4 million people worldwide, according to the Parkinson's Disease Foundation. It also is the second most common neurodegenerative disorder after Alzheimer's disease.

Recent research published in the New England Journal of Medicine found that Parkinson's disease is prevalent in 0.5% to 1% of the population ages 65 to 69 years and in 1% to 3% of people older than age 80.

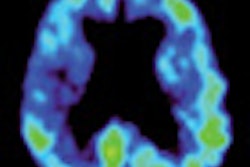

Parkinson's disease is caused by the loss of the neurotransmitter dopamine in the brain. Dopamine stimulates movement, cognition, and memory, and helps neurons connect and communicate in the basal ganglia. Functional imaging of the dopamine deficiency can be done using F-18 DOPA-PET as a marker of dopamine activity.

Mimicking Parkinson's

The diagnosis of Parkinson's disease is based mostly on the clinical assessment of primary motor skills and also secondary symptoms such as dementia, depression, and the loss of energy, which can make the lives of patients very difficult.

"However, there are multiple neurological disorders which can mimic Parkinson's disease, even when a patient presents with typical features," said lead study author Dr. Joanna Kusmirek of the departments of radiology and nuclear medicine at the University of Wisconsin School of Medicine and Public Health. "It may be very difficult for the clinician to establish the proper diagnosis and start the proper therapy."

Kusmirek and colleagues retrospectively reviewed patients who had received DOPA-PET imaging for Parkinson's disease between 2001 and 2008. They found a total of 29 potential subjects, but two people were excluded from the study due to one uncertain diagnosis and one inadequate follow-up.

The remaining total of 27 patients (18 males and nine females) had a median age at scan time of 50.6 years and a total of 28 scans performed. The median length of postscan follow-up was 5.4 years, ranging from two to nine years.

To be eligible for the study, patients must have had at least two years of postscan clinical follow-up and a diagnosis on or after that time that stated whether the patient had Parkinson's disease or not. The eventual diagnosis by the referring neurologist was used as the gold standard for further analysis.

Patients' medical records were assessed for length of follow-up, response to levodopa, clinical course of illness, and laterality of symptoms at time of F-18 DOPA-PET.

An analysis of the 28 scans revealed 20 true-positive results and seven true-negative results. There was one false negative and no false positives. Based on the results, the researchers calculated the sensitivity for DOPA-PET at 95.4%, specificity rated 100%, positive predictive value also was 100%, and negative predictive value was 87.5%.

|

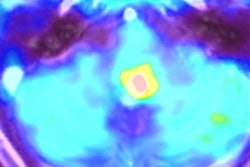

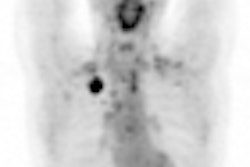

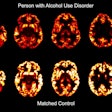

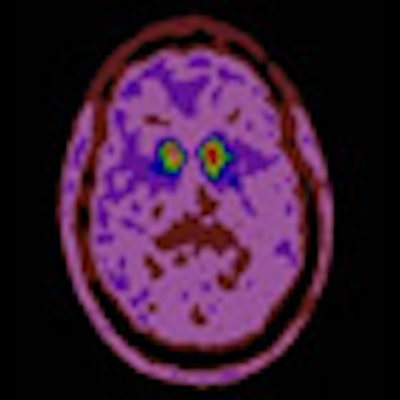

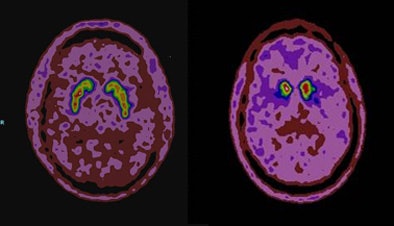

| F-18 DOPA-PET images of a patient without Parkinson's disease (left) and a patient with the disease (right). The left image shows symmetric homogenous uptake of the radiotracer throughout the striatum. The right image shows absent radiotracer uptake to the posterior striatum with still preserved activity in the anterior part of the striatum. Image courtesy of Dr. Joanna Kusmirek. |

"The take-home message is that DOPA-PET is an accurate tool for the diagnosis of Parkinson's disease," Kusmirek concluded in her SNM presentation.

As for potential study limitations, she cited the sample size of 27 patients as small, but added that she and her colleagues believe the total is adequate. Also, the neurologist evaluating the patient data and images was aware of the scan results while making the diagnosis.

"However, we think the follow-up was very adequate for the disease to fully identify itself, because it was a least three years [of follow-up] for most patients, with an average of more than five years [of follow-up]."