People with sedentary lifestyles who exercised regularly over several months showed increased brain glucose metabolism on FDG-PET in one brain region associated with the early onset of dementia or Alzheimer's disease, according to a study published online February 3 in Brain Plasticity.

People who completed a 26-week exercise regimen showed improved cardiorespiratory fitness, which contributed to the enhanced glucose activity in the posterior cingulate cortex. It is this region of the brain where hypometabolism occurs, an early indication of Alzheimer's disease.

"Furthermore, executive function was improved in participants randomized to enhanced physical activity as compared to those maintaining usual physical activity," wrote the authors, led by Ozioma Okonkwo, PhD, from the University of Wisconsin School of Medicine and Public Health. "The present results are consistent with mounting evidence that aerobic exercise training has positive effects on brain structure and function in late-middle-aged adults with normal cognition."

It is well known that regular exercise can improve overall health, regardless of age. Aerobic exercise is associated with better brain volume, which aids memory and executive functions and potentially wards off dementia and Alzheimer's. The question remains, however, whether exercise has the same beneficial effects on people with no Alzheimer's symptoms and who do not participate in regular physical activity.

To find the answer, the researchers enrolled 23 adults between the ages of 45 and 80 into an aerobic exercise training intervention pilot program. Participants showed no signs of Alzheimer's but did have a family history of the disease and a sedentary lifestyle.

Subjects were randomly divided into two groups: One set of 12 adults continued with their usual lack of physical activity and were given information about the importance of a healthy and active lifestyle, while the other 11 adults walked on a treadmill three times per week for 26 weeks. Exercise time increased from 15 minutes in week 1 to 40 minutes in week 6 and to 50 minutes in week 7 to week 26.

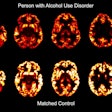

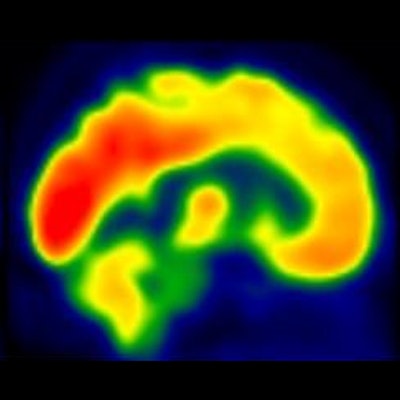

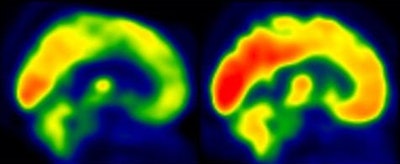

Each image from the FDG-PET scans (Exact HR+, Siemens Healthineers) were "proportionally scaled to the mean FDG signal from the cerebellar vermis and pons," the researchers explained. "We focused on the posterior cingulate cortex, a well-established inception site for Alzheimer's-related neurometabolic alterations."

FDG-PET images represent brain glucose metabolism from a subject with low levels of physical activity group (left) and from a participant in the moderate-intensity aerobic training group (right). Red areas show greater degrees of brain glucose metabolism. Images courtesy of Brain Plasticity.

FDG-PET images represent brain glucose metabolism from a subject with low levels of physical activity group (left) and from a participant in the moderate-intensity aerobic training group (right). Red areas show greater degrees of brain glucose metabolism. Images courtesy of Brain Plasticity.They also measured cardiorespiratory fitness by maximum oxygen (VO2). Peak VO2 in physically active subjects increased from a mean baseline of 23.57 mL/kg/min to 27.46 mL/kg/min after 26 weeks of exercise in the physically active group, compared with 25.74 mL/kg/min and 27.18 mL/kg/min, respectively, in the less physically active group. The increase in peak VO2 was significantly greater in the active subjects than in the more sedentary group (p = 0.018).

The gain in VO2 was associated with both enhanced FDG uptake in the posterior cingulate cortex and significantly better executive function among the physically active subjects, compared with the less active group.

If these findings can be validated in a larger clinical study, it could "provide strong evidence that adults at risk for Alzheimer's disease may enhance brain function and cognition by engaging in aerobic exercise training," Okonkwo and colleagues concluded.