While aerobic exercise is good for the cardiovascular system, PET images show a weekly regimen of this activity does nothing to change the status of beta-amyloid buildup in older adults with elevated levels of the marker for Alzheimer's disease, according to a study published online January 14 in PLOS One.

The findings come from University of Kansas researchers who found no significant changes in beta-amyloid deposits, brain volume, or cognitive performance among more than 100 older adults who took part in a 52-week aerobic exercise program, compared with a control group who received only educational materials.

"Secondary outcomes did not support prior work indicating that aerobic exercise benefits measures of brain health or cognition, at least in a cohort of cognitively normal older adults at elevated risk for Alzheimer's due to elevated cerebral amyloid burden," wrote the authors led by Eric Vidoni, PhD, from the university's Alzheimer's Disease Center. "The observed lack of cognitive or brain structure benefits, despite strong systemic cardiorespiratory effects of the intervention, suggests brain benefits of exercise reported in other studies are likely to be related to nonamyloid effects."

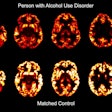

The degree to which a modicum of physical activity delays the onset of Alzheimer's disease and dementia remains up for debate. A 2020 study by Ozioma Okonkwo, PhD, and colleagues found that regular exercise over several months increased glucose metabolism on FDG-PET scans in one brain region associated with the early onset of the disease.

While aerobic exercise is associated with greater brain volume, which in turn helps maintain memory and executive function, the investigators found less verifiable data on how such activity would influence the accumulation of beta-amyloid plaques and tau proteins, two key biomarkers in the advance of Alzheimer's.

To help fill the void, Vidoni and colleagues analyzed 117 older adults (mean age, 72.9 ± 7.7) with no evidence of cognitive impairment and no regular exercise regimen. Of those subjects, 79 people (68%) had elevated levels of amyloid plaque, while the remaining 38 individuals (32%) did not.

The researchers randomized the subjects into one group that participated in moderate aerobic exercise for 150 minutes per week, while the second group was given standard exercise and health information. A total of 110 people completed all 52 weeks of the study.

Participants also underwent PET imaging with florbetapir (Amyvid, Ely Lilly) on a PET/CT system (Discovery ST-16, GE Healthcare) to measure beta-amyloid load in six cortical brain regions and 3-tesla MRI brain scans (Skyra, Siemens Healthineers) to determine changes hippocampal and total gray-matter volume to gauge neurodegeneration.

Scans were performed at the start and conclusion of the 52-week period, with changes in standardized uptake values (SUVs) and whole-brain and hippocampal volume noted. The authors also conducted comprehensive cognitive tests at baseline, after 26 weeks, and at 52 weeks.

At the end of the study period, cardiorespiratory fitness improved significantly in the aerobic exercise group, with an increase of oxygen consumption of 11%, compared with only 1% for the education control group. More importantly, the researchers found no changes in beta-amyloid deposits, brain volume, or cognitive performance between the two groups.

| Impact of exercise program on brain metrics | |||

| Outcome measures | Education control group | Aerobic exercise group | p-value* |

| Global amyloid burden | 0.01 SUV | 0.01 SUV | 0.93 |

| Whole-brain volume | -5.3mL | -2.6 mL | 0.12 |

| Hippocampal volume | 7.4 mL | 7.6 mL | 0.42 |

| Executive function composite | 0.018 | -0.037 | 0.83 |

Aerobic exercise's impotent effect on amyloid accumulation is "surprising," Vidoni and colleagues noted, "given the number of animal exercise studies reporting reduced amyloid accumulation rates and lower amyloid loads. However, small human intervention studies have examined the impact of exercise on amyloid with inconclusive results."

They also suggested that one possible confounding factor to the results is that the amyloid tracer florbetapir "may lack sufficient sensitivity/specificity to index subtle changes in amyloid induced by exercise in cognitively normal older adults."

The aforementioned findings are not the end of the road for this topic. University of Kansas researchers are collaborating with several other U.S. academic institutions in the current "Investigating Gains in Neurocognition in an Intervention Trial of Exercise (IGNITE)" study to validate or refute the results.