Adults who started taking methylphenidate, also known as Ritalin, when they were children for attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) may be able to lay aside concerns over whether the drug has neurotoxic effects, according to authors of an animal study published July 12 in Neurotoxicology and Teratology.

Scientists from the U.S. Food and Administration (FDA) used micro-PET/CT to measure the neurochemical effects of years of high doses of methylphenidate in the study in rhesus monkeys. They found that long-term use did not have a lasting impact on the function of dopamine neurons in the brain.

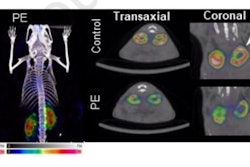

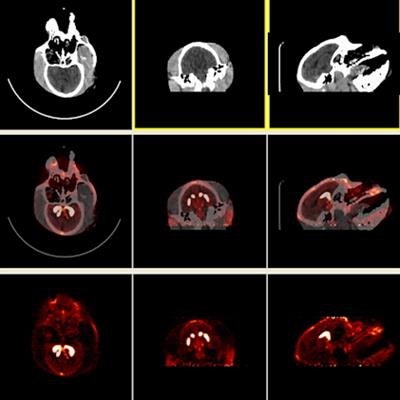

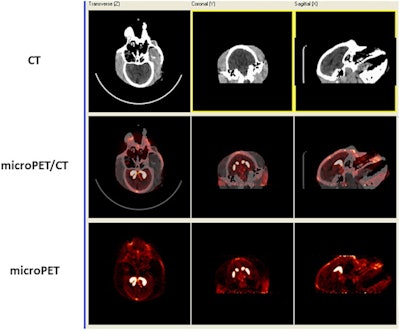

F-18 AV-133 micro-PET/CT brain images from a control monkey. Anatomical CT images are displayed in the top row and the molecular/functional microPET images in the bottom row. Once the images were loaded, the anatomical images were transposed onto the functional images and fused images were created, as seen in the middle row. Image courtesy of Neurotoxicology and Teratology.

F-18 AV-133 micro-PET/CT brain images from a control monkey. Anatomical CT images are displayed in the top row and the molecular/functional microPET images in the bottom row. Once the images were loaded, the anatomical images were transposed onto the functional images and fused images were created, as seen in the middle row. Image courtesy of Neurotoxicology and Teratology."Our data indicate that even at supra-therapeutic dose, long-term use of methylphenidate does not appear toxic to the dopaminergic system," wrote Dr. Xuan Zhang, PhD, of the FDA's National Center for Toxicological Research, and colleagues.

Methylphenidate was first developed in 1944 and approved for medical use by the FDA in 1955. The drug increases levels of dopamine in the brain by blocking the hormone's transporters, which normally remove it once it has been released.

Methylphenidate is generally regarded as "safe," the authors wrote. However, the underlying mechanism of the drug's therapeutic effects is not precisely understood and the long-term effects of early exposure in children with ADHD are unknown. Several studies suggest long-term exposure to methylphenidate during development may in fact prove harmful to the dopaminergic system.

Moreover, methylphenidate has a lot in common with cocaine and methamphetamine, which has caused lingering safety concerns over its use in children, according to the authors.

In this study, Zhang and colleagues sought to investigate the neurotoxic potential of methylphenidate when used across developmental life stages. Rhesus monkeys were chosen because their genetic similarity to humans makes them an accurate model of the human condition.

The researchers began treating the subjects when they were adolescents and continued into their adulthood. The dose of methylphenidate was gradually escalated from 0.15 mg/kg initially to 2.5 mg/kg/dose for the low-dose group, and 1.5 mg/kg to 12.5 mg/kg/dose for the high-dose group. The animals received treatments twice a day, five days per week, for eight years.

The monkeys' brains were imaged once a week with a micro-PET/CT scanner (Focus 220, Siemens Healthineers) using two F-18-labeled PET tracers (AV-133 and FESP) with a high binding affinity for proteins in the striatum brain region involved in transporting dopamine. Micro-CT coronal images were obtained immediately after micro-PET imaging by fusing the anatomical (CT) data with the molecular (PET) data.

The researchers found no significant difference in the binding potential (or uptake) of the F-18 AV-133 tracer between a normal control group and the groups that received both low and high doses of methylphenidate. Both of the methylphenidate monkey treatment groups had a lower F-18 AV-133 binding potential, yet the difference failed to reach statistical significance. Methylphenidate treatment did not have a significant effect on the binding potential of F-18 FESP.

The study was part of a series by the FDA designed to assess the potential developmental neurological, cardiovascular, and genetic toxicity of methylphenidate. While the subjects in this study were healthy, normal rhesus monkeys and not animal models with ADHD, similar methylphenidate treatment using established animal models of ADHD or in patients with ADHD may yield different results, the authors noted.

Nonetheless, the findings are consistent with evidence from other related preclinical studies that suggest long-term treatment with therapeutic doses of methylphenidate has little or no long-lasting neurochemical effects, the scientists wrote.

"These data suggest that, despite lingering concerns, long-term use of methylphenidate does not negatively impact [neurotransmitter] function," Zhang et al concluded.