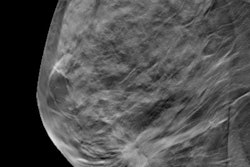

German researchers have created a new molecular microscopy technique that maps the spread of breast cancer at the cellular level, according to a study published November 9 in Nature.

A team led by Artem Lomakin, a predoctoral fellow at the German Cancer Research Center in Heidelberg, found that its method can successfully combine multiplexed fluorescence microscopy-based protocols and algorithms to map and phenotypically characterize cancer subclones. The maps then serve as the basis for further molecular and histological characterization of each clone.

"Particular advantages of the technology are that it is capable of interrogating very large tissue sections on the scale of squared centimeters, which enables studying entire cross-sections of smaller tumors," the study authors wrote. "It is also comparably cheap, unlike solely relying on sequencing-based methods."

While genome sequencing of cancers can reveal different subclones within the same tumor, previous research hasn't determined the spatial growth patterns of particular tumors -- information that could help researchers understand how cancer cells spread and form into tumors.

Lomakin and colleagues sought to develop a way to create quantitative maps of genetic subclone composition across whole-tumor sections. They applied a technology called base-specific in situ sequencing (BaSISS) that uses hundreds of thousands of fluorescent molecular probes to examine cellular DNA and RNA and to scan large pieces of tissue with fluorescence microscopy. The process genetically and physically maps a cancer's unique set of clones, showing how their gene expression changes and how they interact with the body.

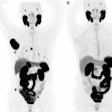

The team tested the technology on eight tissue blocks from two patients who underwent a surgical mastectomy for multifocal breast cancer. It found that clone maps generated for three samples of ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS) formed "striking" patterns of mainly green and orange that localized to areas of histologically confirmed DCIS. Immune clusters and normal or hyperplastic ducts appeared white.

For metastatic lymph nodes, the model detected two clones: P2-blue and P2-orange. These clones formed particular patterns, but only P2-blue was detected in primary breast tumors. The team found that P2-blue cells were located in areas enriched with T cells and B cells, while P2-orange regions were located inside the lymph node sinuses lined by endothelial cells.

This molecular microscopy technique could help investigators develop therapies to inhibit cancer growth and spreading by affecting the environment around tumors, according to the authors.

"Researchers could use ... [this technique] to test how new treatments affect both the cancer and its interaction with the immune system, giving a complete picture of how therapies work and any possible side effects," they concluded.