PET imaging has revealed for the first time that nicotine appears to block a brain enzyme in women involved in estrogen production, according to a study published March 5 in Comprehensive Psychiatry.

Researchers led by Manon Dubol, PhD, of Uppsala University in Uppsala, Sweden, analyzed brain PET images in nonsmoking women before and after they received a nicotine dose equal to a single cigarette. They found evidence that nicotine blocks aromatase in the thalamus and say the work could lead to personalized treatment strategies for women struggling with smoking cessation.

"This work highlights the inhibitory effect of nicotine on aromatase availability in vivo in the thalamus of the healthy female brain," Dubol and colleagues stated. "These findings suggest a new putative mechanism mediating the effects of nicotine on human behavior."

While a wealth of studies points to sex- and hormone-related differences in human behavior and psychiatry, the psychoneuroendocrine underpinnings of these differences remain largely unknown, according to the group.

Carbon-11 (C-11) cetrozole is a PET radiotracer developed by Japanese researchers in 2014 to investigate the physiologic and pathologic importance of aromatase. In the brain, this enzyme is found on neurons that produce estrogen, and thus researchers suspect it influences a number of important processes in women, including perhaps how women respond to addiction.

Thus, in this study, the researchers explored in vivo aromatase availability as seen on PET imaging in relation to exposure to nicotine. The present study is part of an ongoing project that aims to investigate the effect of endogenous and exogenous sex hormones on brain and behavior in healthy women.

Nine women between the ages of 22 and 33 were recruited to participate in two PET imaging sessions scheduled one menstrual cycle apart to ensure a similar hormonal milieu. During the second session, five minutes before the scan, the women received 0.5 mg of Nicorette nasal spray in each nostril to mimic the dose of nicotine in one cigarette.

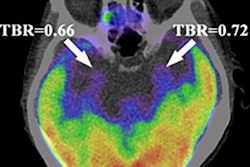

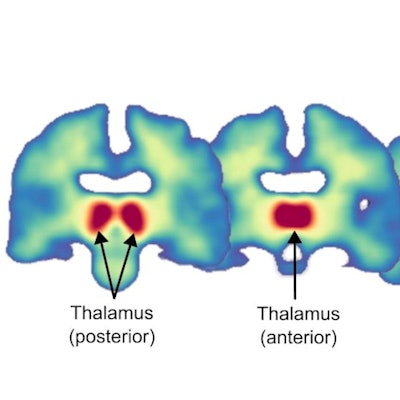

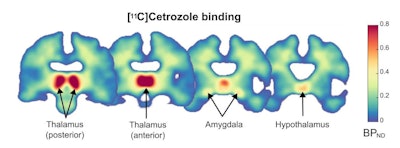

Distribution of C-11 cetrozole binding in the brain of healthy women. Parametric map of C-11 cetrozole non-displaceable binding potential (BPND), averaged across all participants (N=10). Coronal sections of the brain (y = -24, -18, -6, -2) show the highest aromatase availability in the thalamus, followed by the amygdala and hypothalamus. Image courtesy of Comprehensive Psychiatry through CC BY 4.0.

Distribution of C-11 cetrozole binding in the brain of healthy women. Parametric map of C-11 cetrozole non-displaceable binding potential (BPND), averaged across all participants (N=10). Coronal sections of the brain (y = -24, -18, -6, -2) show the highest aromatase availability in the thalamus, followed by the amygdala and hypothalamus. Image courtesy of Comprehensive Psychiatry through CC BY 4.0.Imaging was performed using one of three PET scanners from GE HealthCare. The analysis considered brain areas with reliable binding of the C-11 cetrozole tracer, based on previous reports of PET imaging in humans and nonhuman primates. Regions of interest (ROIs) included the thalamus, amygdala, and hypothalamus.

Overall, eight participants in the analysis displayed a decrease in C-11 cetrozole binding in the thalamus, ranging from a 2% to 36% decrease. No statistically significant nicotine-induced effects were noted in the other two ROIs, the amygdala and the hypothalamus, they reported.

"For the first time, we provide indication of an acute blocking effect of nicotine on aromatase availability in the human brain, especially in the area where the highest level of aromatase binding is found," the authors wrote.

Growing evidence suggests that the thalamus has key roles in motivated behaviors and that there are sex differences in nicotine addiction and treatment response, the authors wrote. Ultimately, the findings of this study translate evidence of aromatase blocking in the thalamus by nicotine observed in nonhuman primates, they wrote.

The present findings, therefore, call for replication in a larger population to confirm the region-specific effect of nicotine on aromatase in the human brain, and to explore these potential sex differences, the authors suggested.

"Future studies following up healthy controls in comparison with nicotine users and nicotine-dependent individuals could shed light on the long-term effect of nicotine exposure and cessation on central aromatase levels," Dubol and colleagues concluded.