Brain pathology associated with Alzheimer’s disease in cognitively unimpaired adults appears to be linked to speech changes, according to neurologists at Stanford University in Palo Alto, CA.

The findings suggest that subtle differences in speech in patients could be used as a scalable approach for early detection of the disease, noted Christina Young, PhD, and colleagues.

“Longer and more between-utterance pauses as well as slower speech rate during delayed memory recall were associated with increased early tau signal,” the group wrote. The study was published February 13 in Alzheimer’s and Dementia.

Speech is central to the diagnosis of Alzheimer's disease (AD), and speech changes have been reported in the mild cognitive impairment and dementia stages, the researchers explained. Yet no studies have examined whether speech patterns relate to biomarkers of AD in the stages preceding cognitive impairment, according to the authors.

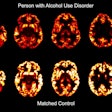

Tau PET imaging detects one such biomarker – neurofibrillary tau tangles – which begin to develop early on in the course of the disease, they added.

In this study, the group culled data from 237 cognitively unimpaired adults enrolled in the Framingham Heart Study (age range, 32-75). Audio recordings of all FHS neuropsychological assessments began in 2005, while a subset of patients in the study underwent structural MRI, amyloid PET, and tau PET imaging.

The researchers first analyzed the recordings and quantified patient speech patterns during a story recall task via five markers: utterance time, between-utterance pause time, number of between-utterance pauses, speech rate, and percentage of unique words. They then examined associations between these speech markers and findings on tau PET.

According to the analysis, longer and more between-utterance pauses and slower speech rate were associated with increased tau PET signal across the participants’ medial temporal and early neocortical brain regions.

Specifically, the strongest associations with between-utterance pause time and number were in the subjects' entorhinal and inferior parietal cortices, which is consistent with hypotheses of early AD progression within the memory system, the researchers noted.

“These results suggest that speech patterns during memory recall provide novel information not captured by traditional neuropsychological testing,” the researchers wrote.

Ultimately, the study supports evidence that speech changes reflect the development of AD tau pathology even in the absence of overt cognitive impairment, the group wrote. This is promising given the potential scalability and ease of collecting and processing speech data, they added.

“Our findings lay the foundation for developing more scalable approaches to capturing speech markers that relate to early tau signal,” the group concluded.

The full study is available here.