PET/MRI could be a tool for diagnosing brain injury in young cancer survivors due to high-dose methotrexate treatment, according to pediatric radiologists at Stanford University in Stanford, CA.

In a pilot study in 10 children and young adults, F-18 FDG-PET/MRI detected brain injury based on reductions in glucose metabolism and blood flow in specific brain areas. The imaging findings could facilitate earlier treatments in these patients, noted lead author Lucia Baratto, MD, and colleagues.

“Using F-18 FDG-PET/MRI for assessing the cerebral impact of methotrexate therapy in pediatric cancer survivors holds the potential to expedite interventions with antiinflammatory remedies and enable effective monitoring of treatment outcomes,” the group wrote. The study was published April 4 in the Journal of Nuclear Medicine.

The five-year overall survival rate of children for all cancers is currently 80% and continues to rise with significant improvements in treatments, the authors explained. However, this has resulted in a growing population of childhood cancer survivors who may face long-term adverse outcomes, they added.

For instance, methotrexate – an antimetabolite agent used routinely to treat various childhood cancers – has been shown in recent studies to activate microglia cells (immune system cells) in the brain, which can lead over time to damaging inflammation, according to the authors.

Hence, the researchers aimed to diagnose such high-dose methotrexate (HDMTX)-induced brain injury using F-18 FDG-PET/MRI in pediatric cancer survivors. Additionally, they sought to correlate these results with cognitive impairment in the patients identified by neurocognitive testing.

The group enrolled 10 children and young adults (9 to 23 years old) with sarcoma (n = 5), lymphoma (n = 4), or leukemia (n = 1) who underwent dedicated brain F-18 FDG-PET/MRI scans followed by two-hour hour expert neuropsychologic evaluation on the same day. All participants had completed HDMTX therapy on average 3.5 months before the time of the brain scan.

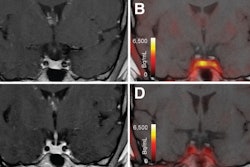

A visual abstract of the study. Image courtesy of the Journal of Nuclear Medicine.

A visual abstract of the study. Image courtesy of the Journal of Nuclear Medicine.

According to an analysis of the images, significant differences in average uptake of F-18 FDG radiotracer (SUVmean) and cerebral blood flow (CBF) were identified among the patients in three specific brain regions: the prefrontal cortex, the cingulum, and the hippocampus, the authors wrote.

“Our data suggest that F-18 FDG-PET/MRI can potentially detect imaging changes indicating HDMTX-induced neurotoxicity,” the group wrote.

Next, the researchers calculated correlations between these findings and the performance of the patients on three neurocognitive tests: the Wechsler Abbreviated Scale of Intelligence (WASI) for intellectual functioning, the Delis-Kaplan Executive Function System (DKEFS) test for executive functioning, and the Wide Range Assessment of Memory and Learning (WRAML) test for verbal and visual memory.

In this analysis, WRAML scores correlated significantly with CBFmean, while DKEFS scores correlated significantly with both SUVmean and CBFmean. Scores on the WASI tests did not correlate with any of the PET/MRI measures, according to the findings.

“Our observations suggest that the SUVmean and CBFmean of the prefrontal cortex and cingulum may serve as quantitative measures for detecting executive functioning issues,” the group wrote.

The authors noted that while it is well known that patients treated with HDMTX may develop neurocognitive problems, the administration of methotrexate has not previously been correlated with the degree or location of specific brain injuries.

“Our data close this gap,” they wrote.

Ultimately, F-18 FDG-PET/MRI shows promise as a noninvasive imaging test for visualizing methotrexate-induced neurotoxicity and could be used to identify childhood cancer survivors at risk for long-term neurocognitive problems, the group concluded.

The full study can be found here.