AuntMinnie is pleased to present Part I of a three-part series on Alzheimer's disease, based on research presented at this year's Society of Nuclear Medicine meeting in Toronto.

How is your memory now compared to five years ago? The answer may be more important than you think.

At the 2001 Society of Nuclear Medicine meeting in Toronto, researchers sought to answer crucial questions surrounding Alzheimer's disease (AD), a progressive brain disorder that has baffled doctors since it was first described by German neuropathologist Alois Alzheimer in 1907.

Ninety-four years later, much remains in doubt -- including what causes the accumulation of certain proteins in the brain, mostly amyloid, that Dr. Alzheimer described. But today's investigators benefit from extraordinary research efforts over the past decade, notably in PET and SPECT imaging, that have enabled the first reliable diagnoses of AD in living patients.

Researchers have recently linked AD with elevated serum cholesterol. And geneticists have found that inheriting one or two alipoprotein E4 alleles of the ApoE gene on chromosome 19 increases the risk of developing late-onset sporadic AD, the most common type of AD that affects more than 90% of patients.

But ApoE4, while significant, is an imperfect predictor, so the question of who will progress to AD remains critical for doctors and patients alike. In this latest round of studies, it is one of the questions nuclear medicine is beginning to answer.

Dr. Daniel Silverman, head of neuronuclear imaging research at the University of California, Los Angeles, found that a perceived loss of memory function correlates strongly with later decline in hippocampal FDG metabolism.

The UCLA study took a different tack from the usual approach of imaging cognitively impaired or at-risk patients, and correlating results with subsequent psychoneurologic decline. Along with colleagues Dr. Linda Ercoli, Dr. Henry Huang, Dr. Gary Small, and Dr. Michael Phelps, Silverman measured FDG metabolism in subjects who initially tested as neuropsychologically normal, and then tried to predict who would later show the greatest declines in cerebral metabolism.

"We're going to turn the paradigm around 180°, and ask if there's some simple neuropsychological parameter that can be measured at one time that will predict what will happen to FDG-PET metabolism in the years following the time of that measurement," Silverman said.

A previous study by his colleague, Dr. Gary Small, found that neuropsychologically normal ApoE4+ subjects nevertheless scored themselves lower than ApoE4- subjects on a quiz designed to elicit perceptions of previous cognitive decline, Silverman said.

"Our first objective was to determine whether there was any metabolic decline that is associated with a self-perceived previous loss of memory function," Silverman said. "And the secondary objective was to see whether this was influenced by the alipoprotein E4 genotype."

To that end, the team acquired neuropsychologic tests, genetic tests, and FDG-PET scans of 39 prospectively recruited normal elderly right-handed subjects. Eighteen of the subjects underwent a second FDG-PET scan at follow-up two years later. Age at time of first scan was 68.6 ± 8.5 years (mean ± standard deviation). Age at the first scan did not differ significantly between those with and without the E4 allele (67.4 ± 9.4 vs. 69.6 ± 8.1).

All PET scans were acquired 40 minutes after administration of 370 MBq of FDG, and changes analyzed using statistical parametric mapping and region-of-interest methods. Cerebral MRI images were also acquired for co-registration purposes.

Half of the subjects carried the alipoprotein E E4 allele (ApoE4+), half did not (ApoE4-), and the two groups were closely matched with respect to age, sex, and educational level, Silverman said.

"First we measured the subjects' perception of memory decline over the years with the Memory Functioning Questionnaire, factor 3 (MFQ3)," he said. "Quite a simple test, except that it turns out to have been very well validated over the last decade in a number of ways. The subject is asked, 'How is your memory compared to the way it was 5 years ago, 10 years ago, 20 years ago, when you were 18?'"

An answer of 1 means that memory has gotten much worse, 7 means much better, and 4 means no apparent change. With five questions on the quiz, total scores could range from 5 to 35. Testing was repeated at the time of follow-up scans, and the results compared to measured changes in FDG metabolism in various brain regions, Silverman said.

Following the initial scan, the subjects' baseline scores ranged from a low of 5 (worst possible score) up to 20 (indicating no overall change), with the average for the whole group being 12.5.

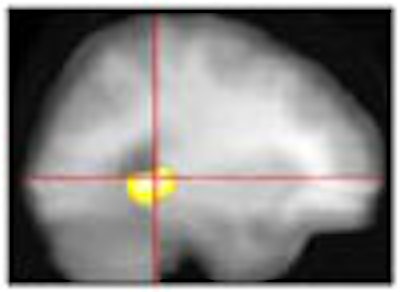

"The most significant correlation was between the lower baseline [MFQ3] scores -- the feeling that your memory declined the most -- and the greater metabolic decline in the posterior hippocampus," over the two-year period, Silverman said. "And we had not predicted this, so we had to apply the most rigorous kind of multiple comparison correction, but even after that correction there was still a significant correlation of P=0.003 [Z=4.82] corresponding to a 0.4% greater decline in hippocampal metabolism for each less point on the scale."

The average change in hippocampal metabolism over 2 years was -4%.

|

While MFQ3 scores were lower in those subjects bearing the E4 allele (10.1 ± 3.9 vs. 14.5 ± 3.3 P=0.02), declines in the left hippocampal region were comparably correlated with declines in MFQ3 results (P<0.005) within each genotypic group. The 39 subjects were genetically heterozygous, differing by a single allele. Moreover, within each group, ApoE4+ and ApoE4- subjects had the same distribution of sex and handedness, Silverman said.

The ApoE4+ subjects' scores ranged from 5-15, and ApoE4- subjects' scores ranged from 10-20, with scores averaging 4.5 points higher in ApoE4- subjects.

"Yet the correlation pattern was very similar between the two groups, so although these groups clustered to a higher point on the MFQ3 scale ... it is still the posterior hippocampus in both groups that shows a very similar extent and significance of involvement," Silverman said.

Silverman concluded that the perceived degree of memory loss correlates strongly with the subsequent decline of hippocampal metabolism in the dominant cerebral hemisphere, in both ApoE4+ and ApoE4- subjects.

"As this brain region is of critical importance in encoding memory of recent events, these data provide localizing evidence of a plausible neurological substrate for the perceived decline," he said.

In response to questions, Silverman defended the idea that two study groups could be balanced based on even rigorous neuropsychological testing, since individuals are in fact subtly different.

It's true that individuals can score nearly the same on several statistical neuropsychological tests, yet show significant variations in performance, he said.

"But if you look at it in a nonparametric way, and ask whether or not they had perfect [Folstein mini mental-state evaluation] scores," about two-thirds of ApoE4- subjects will achieve a perfect score of 30, while only a third of their ApoE4+ counterparts will do as well, Silverman said. "You will see some relatively significant differences in these relatively inconsistent measures."

By Eric BarnesAuntMinnie.com staff writer

September 7, 2001

Related Reading

PET predicts future cognitive decline, June 26, 2001

PET, SPECT differ in Alzheimer's imaging, June 25, 2001

Nycomed Amersham, Neurochem to collaborate on Alzheimer's agents, July 19, 2001

New Alzheimer's guidelines reflect recent "explosion of information," May 8, 2001

SPECT increases accuracy of Alzheimer's diagnosis, April 19, 2001

New PET radiotracer could replace FDG for detecting Alzheimer’s, March 26, 2001

PET and MRI race to detect early Alzheimer’s, January 22, 2001

Copyright © 2001 AuntMinnie.com