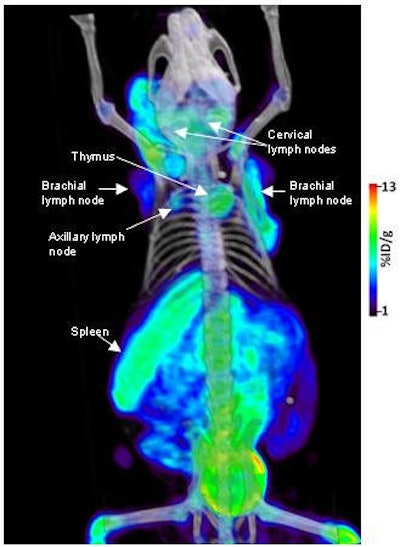

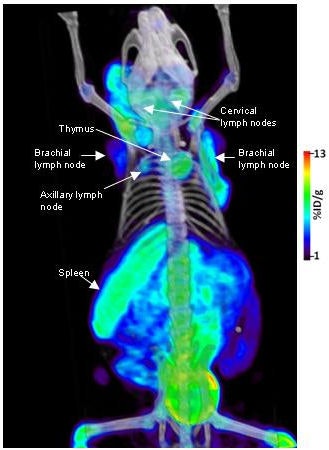

Researchers at the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA) Jonsson Comprehensive Cancer Center have created a new probe for use with PET that shows promise in monitoring the human immune system and its response to new therapies.

The UCLA team slightly altered the molecular structure of the chemotherapy drug gemcitabine to create the new probe. Researchers then added a radiolabel so the cells that consume the probe can be seen in a PET image. This way, physicians can monitor the immune system at the whole-body level in 3D and assess a cancer's progress or regression.

Dr. Owen Witte, senior author of the study and researcher at the Jonsson Cancer Center, emphasized that the probe is not a new treatment for cancer. But it will allow healthcare providers to more effectively model and measure the immune system. By monitoring immune function, physicians could enhance the diagnosis and treatment of immunological disorders and better evaluate the efficacy of certain therapies.

Research details appear in the June 8 online edition of Nature Medicine.

Because the probe is injected and labeled with positron emitting particles, the cells are illuminated under PET scanning. As a molecular imaging camera, PET can detect where the cells go, their quantity, how well they are working, and if there are any side effects.

Patient safeguards

During cell transplantation, cells from a donor "can attack the organism of the recipient," said Dr. Caius Radu, study co-author and assistant professor of molecular and medical pharmacology at the Jonsson Cancer Center. "Therefore, you would like to have some sort of safety mechanism in case something like this happens, which can put the patient's life in danger."

In previous studies, UCLA researchers were able to track the immune system as it recognized and responded to cancer. However, in those studies, the cells had to be modified with "reporter genes" that sequestered a specifically designed PET probe that allowed scientists to monitor them.

"We can take a gene that, upon expression, can enable us to detect a cell type. That gene goes for an enzyme; that enzyme then traps the PET reporter probe," Radu explained. "The advantage of that approach is that if you want to image different biological processes, you only have to use one combination of a PET reporter gene and PET reporter probe."

The disadvantage is that researchers must engineer the expression of a new gene in the cell type to be studied. The most recent research sought a way to eliminate the need for the PET reporter gene. "Not that the [reporter gene] approach is not useful, but you would like to have a way to see the biological process and not have to engineer the expression of any gene," Radu said.

Cell modification

The new probe does not require cell modification, which makes the process less expensive and potentially expands clinical applications. "I think we will see a wave of therapies that rely on treating diseases in different types of cells. Then you would like to have a way to follow these cells once you inject them in the body," he added. "Mostly, we have in mind autoimmune disorders and maybe inflammatory disorders. A third application would be cancer immunotherapy."

Autoimmune syndrome visualized with new molecular probe

The probe has been used in mice and, to a degree, in some human patients at UCLA in clinical trials for brain cancer. Researchers eventually hope to monitor the immune systems of patients with FAC (5-flurouracil, doxorubicin, and cyclophosphamide) and other PET probes.

Human trials

Results of the human trials have not yet been published, but "preliminary results look promising," Radu said. "We can extrapolate from the mouse studies, and from that point of view, I don't see any fundamental flaw in the approach."

The next step for UCLA researchers is to take the PET probe to clinical trials. "It really doesn't matter if you can image or cure cancer in mice, if you cannot show that what you have discovered has value in the clinic," he added. "We are trying to get all the required approvals to do that. Probably in less than a year we should be able to get quite a few patients scanned with this probe."

Researchers from UCLA's Broad Stem Cell Research Center and Crump Institute for Molecular Imaging also participated in the study. The PET scanner was invented by Michael Phelps, a study co-author, director of the Crump Institute, and chair of UCLA's department of molecular and medical pharmacology.

By Wayne Forrest

AuntMinnie.com staff writer

June 12, 2008

Related Reading

ASCO news: PET studies advocated before head and neck, lung cancer surgeries, June 3, 2008

Study evaluates radiation dose, cancer risk for whole-body PET/CT, May 9, 2008

Whole-body PET better for palpable breast cancer, May 2, 2008

Whole-body FDG-PET of little use in breast cancer staging, November 26, 2006

Preop FDG-PET spots axillary involvement in breast cancer, may obviate biopsy, August 21, 2006

Copyright © 2008 AuntMinnie.com