Twenty-five years ago this spring, President Ronald Reagan welcomed the University of Tennessee women's basketball team to the White House to celebrate its first national championship. Sharing the podium with the president was Tennessee coach Pat Summitt, who would go on to earn more wins than any men's or women's coach in college basketball history.

Few that day could have imagined that a quarter century later, they would be connected by another thread as two of the highest-profile public faces of Alzheimer's disease.

But when Summitt announced last August that she was fighting early-onset Alzheimer's -- 17 years after Reagan revealed in a letter to the U.S. people that he had been stricken with the disease -- she vowed to dedicate herself to promoting dementia research. Recently, those efforts were recognized when another president, Barack Obama, announced Summitt as one of this year's recipients of the Presidential Medal of Freedom, in part due to her willingness to "speak so openly and courageously about her battle."

Dr. Gregory Sorensen, CEO of Siemens Healthcare.

Dr. Gregory Sorensen, CEO of Siemens Healthcare.

While medical researchers have made great progress the past 25 years in understanding how the brain works, Alzheimer's disease -- the sixth leading cause of death in the U.S., affecting 5.4 million people -- has been a stubborn foe. Not only is there no cure for the disease, but the only way to know for sure if one has Alzheimer's is through a risky brain biopsy -- actually removing a small piece of brain tissue -- or simply waiting for an autopsy.

There is no other guaranteed path to diagnosis, which is a leading reason why experts believe that 15% to 20% of people who are diagnosed with clinically probable Alzheimer's are diagnosed incorrectly and may receive the wrong treatment.

But with the recent release in the U.S. of the country's first National Alzheimer's Plan, there is a new reason for hope. Since Dr. Alois Alzheimer first discovered abnormal clumps of proteins -- known as amyloid plaque -- in the autopsied brains of diseased patients a century ago, researchers have focused on this plaque as a potential means to prevention, and possibly an eventual cure. However, an imaging solution sophisticated enough to track these plaque deposits in the brain has never been routinely available -- until now.

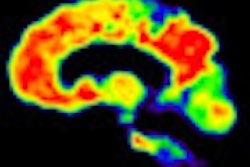

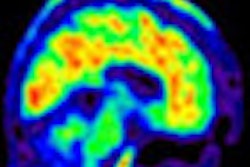

Thanks to pioneering innovations in diagnostic imaging, such as PET, we have the ability to image the body three dimensionally at the molecular level. PET technology, in combination with imaging biomarkers and tailored software, gives us new neuroimaging techniques -- a new window into the brain -- for pinpointing the presence and location of amyloid.

While the presence of amyloid plaque is not always determinative of Alzheimer's, the lack of plaque in a living brain could enable a physician, in concert with other clinical information, to essentially rule out the disease, potentially leading to diagnoses of other root causes that may be treatable.

Conversely, in conjunction with other evaluations, a PET scan that reveals troubling signs of abnormal plaque buildup could indicate the footprint of Alzheimer's. While there are, unfortunately, no definitive treatments for Alzheimer's yet, the knowledge of one's situation early could give patients and their family members more time to plan and make important life decisions. In some cases, symptomatic treatments are available that can help -- treatments that differ if dementia is not due to Alzheimer's.

Differentiating patients is also important when testing new therapies to combat Alzheimer's. If a researcher conducts a clinical trial of 100 patients without realizing that 20 have a form of dementia other than Alzheimer's, the quality of the research and the value of the drug being tested will suffer.

Historically, medical progress -- in oncology, for instance -- is built on incremental gains. As scientists and the medical community continue to pioneer innovative technologies and techniques to better visualize and differentiate problem proteins, we will slowly but surely move from disease detection to discrimination and, ultimately, treatment.

This devastating disease deserves our full attention. Every 68 seconds, someone in the U.S. develops Alzheimer's, which will result in half a million new cases this year alone. With 10,000 Americans reaching the age of 65 every day for the next 19 years, by 2050, Alzheimer's cases are expected to triple, with a diagnosis every 33 seconds.

In that time, the direct costs associated with caring for those with Alzheimer's are expected to quintuple, to $1.1 trillion a year. And that pales next to the human cost, as 15 million family and friends provide an exhausting 17.4 billion hours of unpaid care today to those with Alzheimer's and other dementias. There is no time to waste.

In a recent interview, Pat Summitt recalled watching Ronald Reagan struggle in a TV interview days before he publicly announced his battle with Alzheimer's -- remembering tears coming down her eyes, and thinking "that could be me." That's the problem with Alzheimer's disease: It could be any one of us.

Dr. Sorensen is a neuroradiologist and former professor of radiology at Harvard Medical School. He is the U.S. chief executive officer of Siemens Healthcare.