A new study using PET with a florbetaben radiopharmaceutical shows how people with Down syndrome begin to accumulate beta-amyloid deposits in their brains in their early 40s, putting this population at greater risk for the early onset of cognitive impairment.

Researchers believe these findings also make people with Down syndrome a "unique population" for studying the early development of beta amyloid and how it could lead to Alzheimer's disease, which, in turn, could help assess the effectiveness of amyloid-reducing therapies.

Florbetaben is an investigational radiopharmaceutical currently under review by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and the European Medicines Agency. The developer, Piramal Imaging, has applied for clearance of the radiotracer for the visual detection of beta amyloid in the brains of adults with cognitive impairment who are being evaluated for Alzheimer's disease and other causes of cognitive decline.

People with Down syndrome have an extra chromosome on which there is a gene that can produce a four- to fivefold increase in the expression of amyloid precursor protein (APP), as well as the deposition of beta amyloid in the brain, which has been linked to the onset of cognitive impairment.

"In addition to having the developmental disorder of Down, they also have cognitive impairment that seems to come on earlier than in a person with a dementing illness, such as Alzheimer's," said lead author Dr. John Seibyl, executive director and senior scientist at the Institute for Neurodegenerative Disorders in New Haven, CT. "It is not too surprising, putting two and two together, that amyloid deposition of the brain seems to be associated with dementia and that Down patients at an early age have a good genetic reason for getting [dementia]. Using a noninvasive imaging biomarker of brain amyloid, it made sense to see if we could identify how this occurs as a function of aging."

Age and amyloid

To help narrow the window during which beta-amyloid accumulation occurs, Seibyl and colleagues referred to a 2011 study in JAMA Neurology (formerly Archives of Neurology) that used the radiotracer Pittsburgh Compound B (PiB) with PET imaging on nine subjects with Down syndrome and 14 healthy volunteers. They found that Down syndrome subjects older than 45 years had "significant PiB binding" in regions of the brain associated with Alzheimer's, even when there was no clinical evidence of dementia (JAMA Neurology, July 2011, Vol. 68:7, pp. 890-896).

"We didn't really know when amyloid was laid down, but we did know that if we were able to demonstrate this, it would be an interesting and potentially useful model for the development of amyloid in other disorders such as Alzheimer's and dementia, in terms of the time course," Seibyl added.

The current study, presented at the 2013 Society of Nuclear Medicine and Molecular Imaging (SNMMI) annual meeting, recruited 70 healthy volunteers between the ages of 21 and 40 and 39 individuals with Down syndrome ages 40 or older from two sites. The cognitive status of Down syndrome subjects was measured using the Dementia Screening Questionnaire for Individuals with Intellectual Disabilities (DSQIID).

All 119 individuals received a single injection of 300 MBq (± 20%) of florbetaben, followed by 3D brain PET imaging 90 to 110 minutes after injection.

Both quantitative and qualitative image analyses were performed, and the researchers calculated the standardized uptake value ratios (SUVr) for the frontal cortex, lateral temporal cortex, parietal cortex, anterior and posterior cingulate, and occipital cortex, using the cerebellar cortex as a tissue reference.

Beta-amyloid binding

Seibyl and colleagues found that beta-amyloid binding increased among Down syndrome subjects as they aged. Among the 14 individuals between 40 and 44, two (14%) were positive for beta-amyloid binding. Of the 15 subjects ages 45 to 49, eight (47%) showed beta-amyloid binding, and in the 10 subjects 50 years or older, eight (80%) experienced beta-amyloid binding.

The greatest mean SUVr was seen among individuals with Down syndrome who were older than 50 years. The mean SUVr also steadily increased between those with Down syndrome who were 40 to 44 years of age to those who were 45 to 49 years. As Seibyl and colleagues expected, subjects in the healthy control group had the lowest mean SUVr.

Down syndrome subjects also showed greater mean SUVr in the frontal, lateral temporal, parietal, and posterior cingulate regions of the brain, which deal with cognitive function, than healthy volunteers.

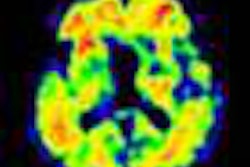

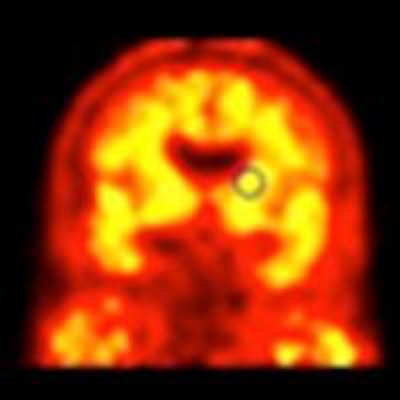

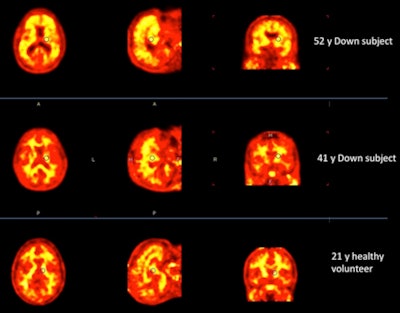

Florbetaben-PET images of three subjects. A 52-year-old with Down syndrome shows beta-amyloid deposits (yellow) extending to the edge of the brain, which indicates uptake in gray and white matter. A 21-year-old healthy subject shows only white-matter uptake, which does not extend to the edge of the brain. Results for the 41-year-old are similar to those of the healthy subject. Images courtesy of Dr. John Seibyl.

Florbetaben-PET images of three subjects. A 52-year-old with Down syndrome shows beta-amyloid deposits (yellow) extending to the edge of the brain, which indicates uptake in gray and white matter. A 21-year-old healthy subject shows only white-matter uptake, which does not extend to the edge of the brain. Results for the 41-year-old are similar to those of the healthy subject. Images courtesy of Dr. John Seibyl.Clinical significance

Seibyl said there are two potentially significant findings from the study. One is the potential development of therapeutic strategies to reduce beta-amyloid plaque burden in the brain.

"It would not be unreasonable to treat Down patients at some appropriate time of their life -- whether that be in their late 30s or early 40s -- to stave off the deposition of amyloid, which will contribute to morbidity for these patients," he added. "They require more care as they have greater cognitive impairment."

The results could also serve as a model of how amyloid deposition occurs in general.

"If it meets the ethical guidelines for clinical research, this might be a better group to look at the potential for amyloid-reducing therapies in a more diffuse, heterogeneous, mild-to-moderate Alzheimer's population," Seibyl said. "[With Down syndrome patients,] things may be changing faster, and you can get a better sense of efficacy without running clinical trials for three years."

One thing that is certain, he added, is that amyloid deposition will happen in people with Down syndrome, and if its progression can be slowed with antibodies, it is "likely that same mechanism or action will be affected in the Alzheimer's population."

Follow-up research

Seibyl and colleagues continue to analyze the data, with a particular interest in younger Down syndrome subjects, such as the 41-year-old participant shown in the clinical images.

"We would like to take this 41-year-old volunteer and follow them over time and look at the individual time course as a progression of development of abnormal radiotracer uptake relative to amyloid deposition in the brain," he said.

Even with the aid of DSQIID, however, clinical assessment of people with Down syndrome can be challenging because they cannot always complete the cognitive tests.

"It is a very rigorous testing schedule for anyone, much less a person with Down," Seibyl explained. "They may become more easily frustrated and they have difficulty in completing the session. All along the way you have to have additional layers of investigational review board or ethical committee oversight, given the population. So the consent process is more difficult."

Still, Seibyl is optimistic that this research will benefit people with Down syndrome, as well as those with cognitive issues and Alzheimer's disease.

Study disclosures

Seibyl has an equity interest in Molecular Neuroimaging and is a consultant for Bayer HealthCare Pharmaceuticals, GE Healthcare, Navidea Biopharmaceuticals, and Piramal Health. Bayer and Piramal Imaging also provided research support for the study.