VIENNA - When Dr. Uwe Haberkorn drew breath after his presentation on Friday's New Horizons session on imaging the hallmarks of cancer, he probably didn't anticipate the lively debate that was to follow.

One view is that ultimately all radiologists and oncologists need to do is to look at "cell kill" and study the dead cells, and the mechanism of cell kill may not be so interesting, pointed out session moderator Dr. Anwar Padhani, a professor of cancer imaging at London's Institute of Cancer Research.

Dr. Anwar Padhani from London.

Dr. Anwar Padhani from London.

"Dead cells have relevance because if you're going to continue using an expensive treatment, you need to know that you are killing cells," he said.

"My opinion is different," responded Haberkorn, who is from the department of nuclear medicine at the University of Heidelberg in Germany. "Do we really in the clinics need to know about cell kill? I think we rather need to know about surviving cells. These are the killers for the patients, not the dead cells. We want to have information about residual tumor tissue. This has therapeutic relevance."

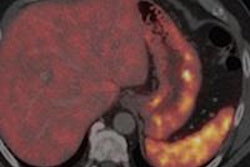

In most cases, a conventional tracer, fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG), can be used to detect dead cells. "If you see the metabolism is going down, then you can see that the therapy works and you can save money," he added. "For cases where FDG doesn't work, do we really need an apoptotic marker or do we need other metabolic markers?"

However, it is important to be careful here and to remember that FDG can increase in certain situations, countered Padhani.

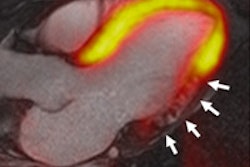

During his talk, Haberkorn explained that biochemical changes occur in apoptosis, including reduction of mitochondrial transmembrane potential, intracellular acidification, production of reactive oxygen species, externalization of phosphatidylserine residues in membrane bilayers, selective proteolysis of a subset of cellular proteins (cysteine aspartic acid specific proteases, or CASPASES), and degradation of DNA into internucleosomal fragments.

Dr. Uwe Haberkorn from Heidelberg, Germany.

Dr. Uwe Haberkorn from Heidelberg, Germany.

He also elaborated on the problems of apoptosis imaging. "Apoptosis is fast, but what is the optimal time for imaging, and is it clinically relevant for all therapeutic approaches?" he questioned, noting that specificity apoptosis-necrosis (annexin) and cell membrane (intracellular targets, CASPASES) were other issues.

The problems of FDG-PET, on other hand, are tumor inflammation, recurrent tumors and radiation necrosis, differentiated tumors (neuroendocrine tumors), and slow growth, as in cases of prostate carcinoma.

According to Padhani, the title of Friday's session, "Imaging the hallmarks of cancer," came from the famous article by Douglas Hanahan and Robert Weinberg, called "The Hallmarks of Cancer" (Cell, January 2000, Vol. 100:1, pp. 57-70). It is one of the most widely read and cited medical articles of all time, having been downloaded more than 30,000 times.

Cancer cells have defects in the control mechanisms that govern how often they divide and in the feedback systems that regulate these control mechanisms (i.e., defects in homeostasis), he explained. Normal cells grow and divide, but have many controls on that growth, and they only grow when stimulated by growth factors. If they are damaged, a molecular brake stops them from dividing until they are repaired; if they can't be repaired, they commit cell suicide, or apoptosis. They can only divide a certain number of times, and are part of a tissue structure and remain where they belong, plus they need a blood supply to grow.

"All these mechanisms must be overcome in order for a cell to develop into a cancer. Each mechanism is controlled by several proteins," he said. "These proteins are damaged when the DNA sequence of their genes is damaged through acquired or somatic mutations, i.e., mutations that are not inherited but occur after conception. This occurs in a series of steps, the outcome of which Hanahan and Weinberg call hallmarks."

Originally published in ECR Today on 8 March 2014.

Copyright © 2014 European Society of Radiology