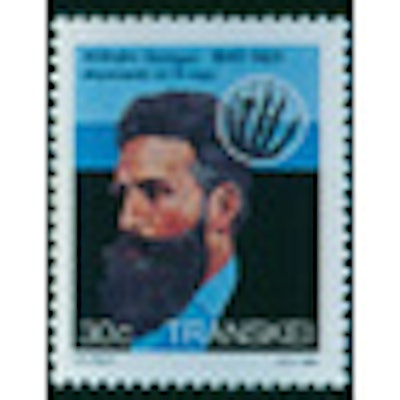

Three years after Wilhelm Roentgen's 1895 discovery of x-rays, three French scientists, Henri Becquerel and Pierre and Marie Curie, figured out how to extract a product called radium from mineral substances. Excitement immediately grew in the U.S. and Western Europe about radium's potential for the treatment of cancer patients.

The production of isotopes in the U.S. started in the early 1930s with the activities of physicist Ernest O. Lawrence, a professor at the University of California, Berkeley. Lawrence cooperated in the use of his cyclotrons with Dr. Robert Stone, the radiology chief across the bay at the University of California, San Francisco. Stone brought a few cancer patients to the cyclotrons and also tested some new 18 isotopes, including sodium-24 and phosphorus-32.

At the end of 1941, the U.S. entered World War II, and the government's Manhattan Project resulted in the creation of three atomic bombs, one tested in New Mexico and two exploded in Japan. Lawrence, Stone, and other physicists as well as some physicians had been involved with the atomic bomb and the development of radioisotopes. In 1946, the U.S. Congress created the Atomic Energy Commission, which furnished radioisotopes to scientists and doctors.

A new specialty

A few years later, some radiologists and other doctors were testing isotopes for cancer patients. By 1950, the American Board of Radiology (ABR) had decided to develop a specialized exam for radiologists to qualify for the use of isotopes for medical diagnosis as well as treatment.

Soon thereafter, a group of doctors and others interested in isotopes founded the Society of Nuclear Medicine (SNM), and the first meeting was held in Seattle in 1954. Dr. Tom Carlyle, a radiologist, became the first SNM president, and efforts were made to attract other doctors from around the U.S. Some of the participants were not radiologists, and they contended that the use of isotopes should be a separate medical specialty from radiology.

ABR had explored the possibility of adding courses on isotope use to radiology resident training in hospitals in 1956. However, the managers of SNM felt that isotope use should be a separate discipline and require specific training, as well as a separate certification from that used by radiology organizations.

This prompted a series of discussions seeking the approval of the American Medical Association (AMA) for a dedicated exam. The American College of Radiology (ACR) and ABR sought to include isotopes with radiology, but other advocates for SNM wanted a separate certification. Eventually, AMA approved a separate isotope structure, and in 1971 the American Board of Nuclear Medicine (ABNM) was formed to administer the program.

With the enthusiasm for isotopes, some medical schools obtained separate training programs for medical graduates entirely apart from the resident training of radiology and other disciplines. However, ABR had imposed requirements for diagnostic radiologists to have a substantial portion of isotope training along with other x-ray elements.

In the early years of its founding, SNM proposed annual national meetings and some cooperation with international sessions. In 1959, it started the Journal of Nuclear Medicine, which it still published today. SNM also chose to create a section of nuclear technologists, which also continues.

In 1990, SNM decided to move its office from New York City to a new national headquarters in Reston, VA. Now known as the Society of Nuclear Medicine and Molecular Imaging (SNMMI), the group lists 18,000 physicians and technologists among its members and continues with its journal and yearly conventions.

Otha W. Linton, MSJ, retired in 1997 as the associate executive director of the ACR after 35 years. He also served as executive director of Radiology Centennial in 1995. Mr. Linton holds a bachelor's degree in journalism from the University of Missouri and a Master of Science in journalism from the University of Wisconsin. His work has been published widely in the U.S. and abroad, and he is a regular contributor to several journals including Academic Radiology, the American Journal of Roentgenology, Radiology, and the Journal of the American College of Radiology. He joined the ACR staff in 1961 and had a key role in its growth. Over the years, his responsibilities with the ACR included government affairs, public relations, marketing, publishing, industrial liaison, and international relations. Just before his ACR retirement, he became the executive director of the International Society of Radiology and served in that role until 2012. Also, since his retirement, he has written and published several histories of radiology societies and academic centers.