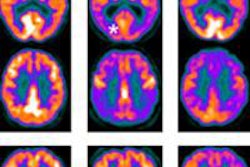

Researchers have found that using PET brain imaging with florbetapir and FDG can differentiate cardiovascular disease from symptoms of mild cognitive impairment or Alzheimer's disease. The combination can also detect amyloid plaques in patients with cardiovascular disease.

The study from Thomas Jefferson University in Philadelphia could lead to more accurate diagnoses of people with mild cognitive impairment, with or without cardiovascular disease.

Previous research has suggested that individuals with cardiovascular disease may be at greater risk for Alzheimer's, noted lead author Nancy Wintering, research program manager at Thomas Jefferson.

"However, the discussion in this area is just beginning," she said. "From the perspective of providing good quality treatment and using imaging thoughtfully, we feel there is a benefit in using FDG and florbetapir. Both agents have been found to be very good imaging agents to identify whether or not individuals have Alzheimer's disease."

For the past 12 years or so, Wintering has worked with Dr. Andrew Newberg, a professor of radiology and emergency medicine, on phase I and phase II trials with contrast agents, some of which were developed to view amyloid plaque. Their most recent research was featured in a poster presentation at last month's Society of Nuclear Medicine and Molecular Imaging (SNMMI) annual meeting.

Subjects in the study were referred for evaluation by neurologists for possible Alzheimer's disease or neurodegenerative disorders. They were checked for comorbid conditions, and MRI scans were reviewed to ensure individuals did not have other clinical concerns that might affect PET imaging.

Cardiovascular connection

"Many patients coming in for evaluation for mild cognitive impairment are going to have cardiovascular disease," Newberg said. "In fact, it was a very substantial percentage of our group. More than half had cardiovascular disease."

The researchers enrolled 26 patients with mild cognitive impairment or Alzheimer's, with each participant receiving separate FDG-PET and florbetapir-PET brain scans. Of the 26 patients, 17 had cardiovascular disease (11 men, six women; age range, 41-77 years). Seven men and two women (age range, 52-84 years) did not have cardiovascular disease. Nuclear medicine physicians read the scans and were blinded to the patients' age, gender, and clinical diagnosis.

The review of FDG-PET images showed lower metabolism in subjects with no cardiovascular disease compared to those with cardiovascular disease. More specifically, FDG-PET showed significant differences between the cardiovascular disease in the right parietal lobe and in the posterior cingulate. There were no significant differences in other brain regions.

Florbetapir showed greater binding to beta-amyloid plaque in the bilateral, frontal, and parietal lobes, as well as in the right temporal lobe and anterior and posterior cingulate, in the noncardiovascular disease group compared to patients with cardiovascular disease.

Amyloid plaque binding in regions such as the frontal lobe, temporal lobe, parietal lobe, and cingulate gyrus is significant because they are associated with memory and other cognitive functions, and the accumulation of amyloid plaque can be an early indication of Alzheimer's or other cognitive impairment.

In both groups, the researchers found good concordance between amyloid plaque and FDG scans for Alzheimer's.

"In general, we found with FDG-PET, people who did not have cardiovascular disease tended to have lower metabolic activity," Newberg said. Those without cardiovascular disease also had greater amounts of florbetapir binding.

The findings are important, he added, because they can help physicians know what kind of results to expect in terms of sensitivity, specificity, and so forth in patients who have certain characteristics of cardiovascular disease versus those who do not.

Clinical implications

"When we see people who do not have cardiovascular disease having worse metabolism and higher amyloid, that's probably more reflective of the fact that that population is more likely to just have Alzheimer's disease," Newberg said. "Whereas the cardiovascular disease people are more likely to have other issues in addition to Alzheimer's. It is reflected in more amyloid binding, but not to the degree of people who do not have cardiovascular disease."

Wintering hopes the study results will lead to closer collaboration with neurologists in making informed referrals for the treatment of cardiovascular disease and help identify patient populations that could benefit from therapy.

"It would be a good idea to see what happens with individuals presenting with mild cognitive impairment symptoms and address the cardiovascular symptoms, perhaps with some lifestyle and behavioral changes, such as exercise, that potentially would have a positive effect," she said.

Study disclosures

The study was funded by a grant from the National Institutes of Health and Avid Radiopharmaceuticals, which markets florbetapir under the trade name Amyvid in the U.S. and Europe with parent company Eli Lilly.