SPECT is once again showing its value by distinguishing the fine line between post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and traumatic brain injury (TBI) in nonmilitary patients, which should lead to better treatment for the disorders.

In the study, published online July 1 in PLOS One, SPECT achieved at least 80% sensitivity for distinguishing TBI from PTSD in a group of patients with a wide range of comorbidities.

The researchers intentionally chose not to limit or match comorbidities among the subjects to evaluate a more "real-world" sample of a patient population, "where we see everybody in the clinical setting who might have any combination of comorbidities in terms of depression, anxiety, TBI, PTSD, and so on," said study co-author Dr. Cyrus Raji, PhD, a radiology resident at University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA).

The ability of SPECT to diagnose such a diverse cohort of TBI and PTSD patients "means that even in a large, real-world sample, these patients in the community are still getting good results with this imaging approach," Raji added.

The results follow research earlier this year in which Raji and colleagues validated SPECT's efficacy in distinguishing PTSD and TBI in a military population. SPECT clearly showed perfusion differences in the brain's default mode network that could help radiologists distinguish TBI from PTSD among these patients.

Also, in a 2014 study, Raji and colleagues found that SPECT imaging for TBI improved lesion detection compared to CT and MRI and helped predict clinical outcomes and direct treatment. Thus the authors suggested that SPECT be part of a clinical evaluation in the diagnosis and management of TBI (PLOS One, March 19, 2014).

TBI, PTSD similarities

The findings in the current study and past research are particularly relevant because mild TBI often goes undetected using conventional structural imaging, the authors noted, while chronic TBI symptoms often mirror and overlap those of PTSD.

The greatest concern is that treatment for TBI and PTSD differs greatly and a misdiagnosis can lead to inappropriate follow-up.

"The pharmacological treatments for PTSD, such as benzodiazepines and atypical antipsychotics, can impede function or be dangerous in those who have TBI," the authors wrote. "Similarly, antipsychotics ... have been shown to impede recovery or be contraindicated in clinical studies and animal models of TBI."

Say, for example, that a patient has both PTSD and TBI, which is common, Raji said. If brain scans functionally show more of a TBI pattern than a PTSD pattern, this helps physicians tailor the patient's treatment plan.

"The whole idea is to make sure that the best treatment is optimized and tailored based on what we are seeing clinically and also what happens in the scans," he said.

In addition, one of the challenges in differentiating TBI from PTSD in a civilian population is the greater number of ways nonmilitary people can be injured, whereas armed forces personnel generally have blast injuries with direct impact.

Effects on brain regions

Not surprisingly, there are similarities in terms of the brain regions affected by TBI and PTSD. For example, the frontal lobes are adversely affected in both sets of patients.

"The hippocampus is also an important region for which differences in blood flow activity can help distinguish between PTSD and TBI," Raji said. "It is the same situation with the anterior cingulate gyrus. The regions become important because of their vulnerability. Whether it be physical or emotional trauma, it is still there."

For the current retrospective analysis, the researchers used a database of 20,746 patients who were evaluated for psychiatric and/or neurological conditions at one of nine outpatient clinics between 1995 and 2014.

The study consisted of two groups. The first one included 104 patients with TBI, 104 with PTSD, 73 with both TBI and PTSD, and 116 healthy controls. The subjects in this group were matched closely in terms of demographics and comorbidities, with little variance.

The second group was much larger and included a broader range of psychiatric comorbidities. It was composed of 7,505 people with TBI, 1,077 with PTSD, 1,017 with both TBI and PTSD, and 11,147 with neither TBI nor PTSD.

All SPECT scans were performed on a high-resolution, triple-head gamma camera (Prism XP 3000, Picket International/Philips Healthcare).

Raji and colleagues evaluated rest and task-based SPECT images by analyzing regions of interest (ROI) and visual readings of the scans.

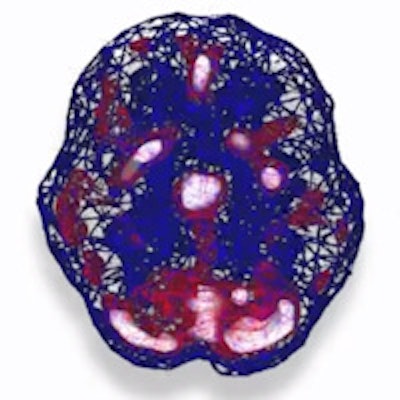

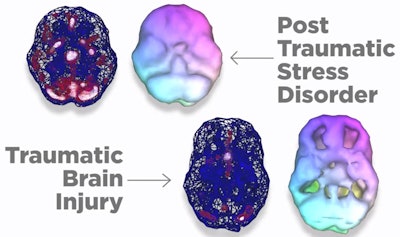

Top images illustrate increased perfusion in subjects with PTSD as reflected by the increased red and white throughout the brain (top left). Bottom images show decreased blood flow due to physical trauma in TBI as reflected by the decreased white and red, as well as holes in the volume-rendered image (bottom right). Image courtesy of Dr. Cyrus Raji, PhD.

Top images illustrate increased perfusion in subjects with PTSD as reflected by the increased red and white throughout the brain (top left). Bottom images show decreased blood flow due to physical trauma in TBI as reflected by the decreased white and red, as well as holes in the volume-rendered image (bottom right). Image courtesy of Dr. Cyrus Raji, PhD.In the first group, they found that SPECT provided "significant separations" between patients with PTSD, TBI, and both conditions, with sensitivity, specificity, and accuracy of 100% in the ROI analysis and more than 89% accuracy in the visual readings.

In the second, more-diverse group, sensitivity was lower but still at least 80% for distinguishing TBI from PTSD.

"In the civilian community, there are many more different types of causes [of TBI]," Raji said. "Even in this large civilian population, there are so many different things that can be happening, but we still get 80% to 82% sensitivity."

In terms of brain regions, subjects with PTSD showed increased perfusion in the limbic structures, cingulum, basal ganglia, insula, thalamus, prefrontal cortex, and temporal lobes, compared with those with TBI.

The future of neuroimaging

While SPECT is commonly available in the outpatient setting for functional neuroimaging applications, other modalities may also contribute to the study of TBI and PTSD, Raji said.

Previous research has shown there is "no reason we cannot adapt functional MRI and other techniques such as PET and diffusion-tensor MRI to evaluate these disorders as well," he said.

As this field evolves, different practitioners likely will favor one imaging modality over another, based on factors such as personal preference, availability of the modality, and the ability to communicate "actionable" information to the patients, he noted.

"How well we do that as a field will determine which one of these techniques ultimately becomes dominant. Ultimately, we will find that they all provide complementary information," he said. "My thinking is, we can use different functional imaging techniques, but because the SPECT modality has been around longer, there is an opportunity for this clinical population to be developed."