Imagine being able to restore consciousness to a patient who has been comatose for 15 years. French researchers succeeded in accomplishing that goal, with the help of PET and electroencephalography (EEG) to confirm the efficacy of vagus nerve stimulation, according to a study published online in Current Biology.

The findings run counter to the common belief that patients who are in a comatose or vegetative state for more than 12 months have little or no chance of recovery. By sending electric stimulation to the vagus nerve in the brain, the researchers brought their patient back to the point where he was able to obey verbal commands after only one month of treatment.

"Changes even in severe clinical patients are possible when the right intervention is appropriate and powerful," said study co-author Dr. Angela Sirigu from the Institut des Sciences Cognitives - Marc Jeannerod in Lyon. "Specifically, I believe that this treatment can be important for minimally conscious patients by giving them more chances to communicate with the external world."

Target the vagus

Whether a patient can recover from a vegetative state naturally depends greatly on the extent of brain damage, particularly in the cortex, thalamus, brainstem, and white matter. Any hope of recovery is often tied to increased activity in the thalamocortical region and improved frontoparietal function (Current Biology, 25 September 2017).

In this study, the researchers targeted the vagus because it modulates activity in the brainstem and connects with the thalamus, amygdala, and hippocampus. The vagus also is associated with essential functions such as waking from sleep and alertness.

Vagus nerve stimulation is already being used to treat epilepsy and depression, and it has been shown to increase cortical metabolism and activity in the forebrain and thalamus by enhancing neuronal activity, which in turn heightens arousal and responsiveness.

To test the validity of this stimulation technique, the French researchers chose a patient who had been in a vegetative state for 15 years after a car accident and showed no sign of improvement.

"We therefore put ourselves in a difficult challenge by selecting a patient with the worst outcome," Sirigu wrote in an email to AuntMinnie.com. "If changes were observed after vagus nerve stimulation, these [improvements] could not be the result of chance."

The process began with the surgical implantation of a stimulator. The device resembles a pacemaker and is designed to send electric impulses to the vagus nerve. Stimulation increases gradually to a maximum intensity of 1.5 mA over the first month of treatment.

PET and EEG

To monitor the patient's response to the stimulation, a scalp EEG was used to gather data on brain signals, which can help clinicians differentiate between a vegetative state and minimal consciousness. The researchers compared resting-state results with the patient's condition before, during, and after treatment.

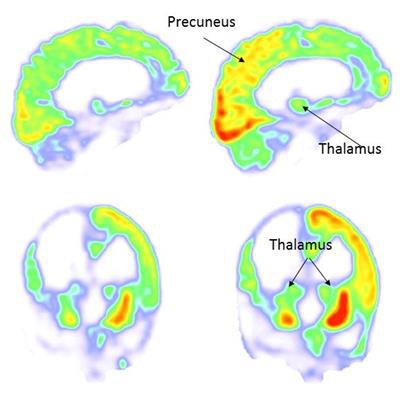

They also performed a baseline FDG-PET scan before stimulation and again three months later to determine any differences in brain activity. In fact, PET has been widely used for patients in vegetative states because the modality seems more sensitive to changes than blood-oxygen-level dependent (BOLD) functional MRI (fMRI), Sirigu noted. Also, the metallic vagus nerve stimulation device was a contraindication for MRI.

It did not take long for the researchers to notice changes in the patient's condition. After one month of stimulation, he was able to respond to simple orders such as following an object with his eyes and turning his head on command.

"After stimulation, we also found responses to threat that were absent before implantation," Sirigu said. "For instance, when the examiner's head suddenly approached close to the patient's face, he reacted with surprise by opening his eyes wide. The reaction indicated that he was fully aware that the examiner was too close to him."

The patient's progress was further illustrated by the PET images, which revealed extensive increases in metabolic activity in the form of glucose consumption in cortical and subcortical regions, including the thalamus, striatum, inferior parietal, precuneus, posterior cingulate, and premotor/motor regions.

![FDG-PET images taken at baseline (left, before vagus nerve stimulation [VNS]) and three months after stimulation (right) show increased activity in the right parieto-occipital cortex, thalamus, and striatum (right, red). Images courtesy of Current Biology.](https://img.auntminnie.com/files/base/smg/all/image/2017/09/am.2017_09_25_16_39_6113_PET_pre_post_VNS_MOL_Insider_20170925162525.png?auto=format%2Ccompress&fit=max&q=70&w=400) FDG-PET images taken at baseline (left, before vagus nerve stimulation [VNS]) and three months after stimulation (right) show increased activity in the right parieto-occipital cortex, thalamus, and striatum (right, red). Images courtesy of Current Biology.

FDG-PET images taken at baseline (left, before vagus nerve stimulation [VNS]) and three months after stimulation (right) show increased activity in the right parieto-occipital cortex, thalamus, and striatum (right, red). Images courtesy of Current Biology."FDG-PET results corroborated EEG findings by showing extensive increases of activity in occipito-parieto-frontal and basal ganglia regions as early as three months after implantation of the stimulator," the researchers wrote. "Vagus nerve stimulation [also] enhanced the metabolic signal in the thalamus, a target of the vagus nerve."

No surprise

Sirigu said she and her colleagues were not surprised by the results. She cited previous animal studies that showed similar patterns of brain changes after vagus nerve stimulation.

"It was particularly comforting to find that the changes we observed after vagus nerve stimulation match perfectly with what is reported in human patients when their clinical state spontaneously shifts from vegetative to minimally conscious," she said. "This suggests that vagus nerve stimulation activated a natural physiological mechanism."

Certainly, the results are encouraging for patients in a vegetative state and their families. The findings indicate that improvements among even severe clinical cases are possible with the appropriate intervention.

"Brain plasticity and brain repair is still possible even when hope seems to have vanished," Sirigu said. "I believe this treatment can be important for minimally conscious patients by giving them more chances to communicate with the external world."

The researchers plan next to conduct a large collaborative study with several clinical research centers to confirm and extend the therapeutic potential of vagus nerve stimulation.

"As a cognitive neuroscientist, my goal is also to understand the neural mechanisms of consciousness," Sirigu said. "More basic research will be important for advancing our understanding of this fascinating capacity of our mind to produce a conscious experience."