ANAHEIM, CA - By identifying increased metabolic activity or inflammation associated with chronic pain, FDG-PET/MRI can improve care management strategies for a majority of patients, according to a study presented Sunday at the Society of Nuclear Medicine and Molecular Imaging (SNMMI) annual meeting.

Researchers from Stanford University School of Medicine found that more than 50% of subjects in their study had their pain treatment changed to more serious courses of action after clinicians were able to accurately determine the cause of the pain. It was the combination of PET and MRI that made the diagnoses possible.

"It is not surprising that FDG is more sensitive than MRI for detecting inflammation, but, as we know, FDG is fraught with being nonspecific," said study co-author Dr. Sandip Biswal, associate professor of radiology and musculoskeletal imaging at Stanford. "It can take up in nonpainful inflammatory conditions, such as arthritis, or situations where pain is due to overuse of a muscle or body part to overcompensate for another."

Pain is No. 1

The number of people seeking medical attention for pain is greater than the number of patients with cancer, diabetes, and heart disease combined – making it the most common reason for people to see a physician. Pain is also the No. 1 reason why people miss a workday.

"Unfortunately for these patients, we lack objective tools to diagnose their pain generator," Biswal told SNMMI attendees. "We can take a group of asymptomatic individuals with middle-age pathology, and, of course, we will see herniated discs, meniscal tears, and rotator cuff tears. But what do these findings mean for patients with pain?"

For this study, Stanford researchers looked at 64 patients who were referred for imaging for a variety of conditions that included lower back pain, sciatica, joint pain, and occipital neuralgia. Scans were performed on a PET/MRI system (GE Signa, GE Healthcare) that features a 3-tesla scanner and time-of-flight PET.

Patients underwent imaging one hour after a 10 mCi injection of FDG. MRI sequences included a coronal double-echo steady state (DESS), isotropic coronal steady-state free precession, and axial T2-weighted fast spin echo (FSE) with fat saturation. Scan time included four to eight minutes of imaging per bed position.

"One of the interesting tricks we are using is to image from head to toe, even if the patient only has knee pain, simply because if you have knee pain, it doesn't necessarily mean it comes from the knee," Biswal explained. "It could come from your back or referred pain from your lower foot. By capturing the entire body, perhaps we can diagnose why you are in pain."

Pain finders

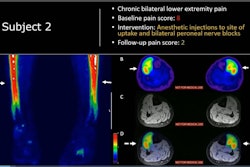

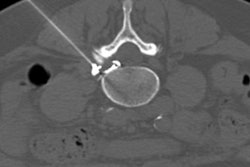

PET/MR images identified focal increased FDG uptake in the affected nerves and muscle, with maximum standardized uptake values (SUVmax) ranging from 0.9 to 4.2. Those results were more than double SUVmax for background tissue, which ranged from 0.2 to 1.2. The higher SUVmax readings naturally helped the researchers pinpoint the pain generators.

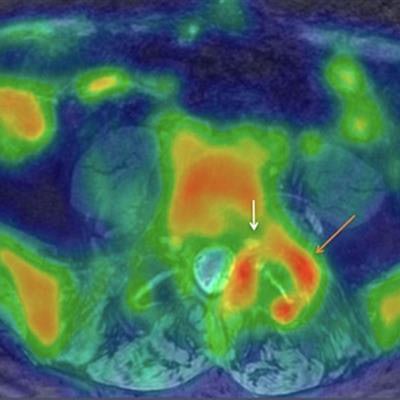

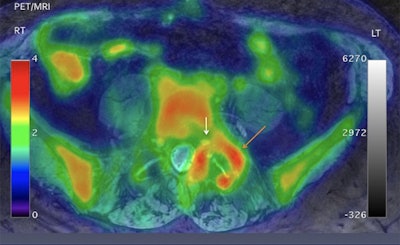

Axial projection of a 57-year-old male with low back pain down to the left groin, leg, and foot. Significant asymmetric uptake of FDG is seen around the left facet joint (orange arrow; SUVmax 2.94), compared with the right facet joint (SUVmax 1.2). Increased tracer uptake is adjacent to left foraminal segment of the left nerve root (white arrow). Images courtesy of Biswal et al and SNMMI.

Axial projection of a 57-year-old male with low back pain down to the left groin, leg, and foot. Significant asymmetric uptake of FDG is seen around the left facet joint (orange arrow; SUVmax 2.94), compared with the right facet joint (SUVmax 1.2). Increased tracer uptake is adjacent to left foraminal segment of the left nerve root (white arrow). Images courtesy of Biswal et al and SNMMI.Imaging results were discussed with the patients' referring physicians who then made the decision whether to change the pain management plan.

With the updated PET/MRI information, physicians made significant changes in pain care for 36 patients (56%). The alterations included changes in medication and/or a minimally invasive or surgical procedure. In addition, 15 patients (23%) had a mild modification -- which included an additional diagnostic test such as an MRI, ultrasound, or electromyogram -- and 13 people (20%) had no change to their plan.

The change in the pain management plan in more than half of the patients "was not anticipated by the referring physician," Biswal added. "We are now making all the outcome measurements to see if these changes in management will help [the patients]."