Barbecues, bare feet, pool parties, and fabulous fireworks are just a few of the elements of summer that people know and love. But the next few months aren’t all about freewheeling days and beach blanket bingo. Summer is also the peak time for the dissemination of Lyme disease.

The risk of falling victim to the disease is greatest in early summer. It's the time of year when people -- and children in particular -- are most active outdoors, according to a report released by the U.S. Centers for Disease Control.

There were nearly 17,000 reported cases of Lyme disease in the U.S. in 1999, the last year for which final CDC figures are available. The American Lyme Disease Foundation states that more than 100,000 cases have been reported since 1982, making Lyme disease the most common athropod-borne illness in the U.S.

Lyme disease is a multisystem organ disease caused by the spirochete Borrelia burgdorferi, a type of bacterium. An infected tick transmits the spirochete to the humans and animals that it bites. If untreated, the bacterium travels through the bloodstream and establishes itself in various body tissues, starting with the skin and potentially spreading through the nervous system.

The majority of these cases have occurred in New York, Pennsylvania, and New Jersey. The prevalence of the disease in the Northeastern U.S. can be blamed on the high population of deer and white-footed mice -- the hosts with the most for deer ticks.

While imaging specialists are not generally called upon in the treatment of Lyme disease, they can play an important part in determining how far the infection has spread, especially when symptoms aren’t obvious. Radiologists from the Mount Sinai School of Medicine at New York University in New York City used MRI to pinpoint orbital Lyme disease in a patient who showed no signs of seriously impaired vision. Dr. Girish Fatterpekar, Dr. Peter Som, and colleagues shared their results in a case study in the American Journal of Neuroradiology.

"Ocular involvement is not commonly observed in association with Lyme disease, but the spirochete may also remain dormant in the eye, accounting for late ocular manifestations," they wrote. Orbital findings that have been associated with Lyme disease include follicular conjunctivitis, inflammatory syndromes, and, most commonly, keratosis (AJNR, April 2002, Vol.23:4, pp.657-659).

Over the long term, chronic Lyme neuroretinitis may be unresponsive to antibiotic therapy (Retina, 1996, Vol.16:6, pp. 505-509).

In this case, a 46-year-old New Jersey man presented with a two-week history of headache and diplopia. He had no orbital pain, although a "marked restriction of lateral gaze and 3-mm proptosis of the right eye was noted." The results of the ophthalmic and physical exams were normal, and no evidence of neurologic deficit was detected.

|

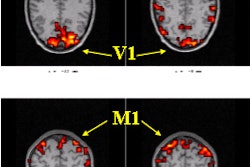

Axial (top) and coronal (below) contrast-enhanced, fat-suppressed T1-weighted images through the orbits demonstrate diffuse homogeneous thickening of the medial, lateral, and inferior rectus muscles of the right orbit. There is minimal thickening of the superior muscle group. The tendinous insertions are not involved. There are also scattered inflammatory changes in the ethmoid sinuses and the left maxillary sinus. |

The patient underwent MR imaging on a 1.5-tesla Signa scanner (GE Medical Systems, Waukesha, WI). Gadolinium-enhanced, fat-suppressed, T1-weighted images were obtained through the orbits. Contiguous images of 4 mm with a 1-mm interslice gap in the axial and coronal planes were obtained, Som told AuntMinnie.com.

Prior to treatment, the MR scans showed "diffuse homogenous thickening of the medial, lateral, and inferior rectus muscles of the right orbit." In addition, scattered inflammatory changes in the ethmoid sinuses and left maxillary sinus were seen, the group reported.

The patient underwent treatment with the antibiotic doxycycline for three weeks. Three months later, post-treatment MR exams showed complete resolution of the homogenous muscle thickening, and some inflammatory changes in the sinuses that eventually resolved themselves.

|

| Axial contrast-enhanced, fat-suppressed T1-weighted image through the orbits, post-treatment with doxycyline, demonstrates complete resolution of the previously noted homogeneous muscle thickening. There remain scattered inflammatory changes in the ethmoid sinuses and the left maxillary sinus. Images courtesy of Dr. Peter Som. |

Imaging the orbits of patients with suspected Lyme disease is not done as a matter of course at his institution, Som said. However, differential diagnosis of ocular lesions should be considered if there is no evidence of other disease conditions.

Researchers from University Erlangen-Nurnberg in Germany came to a similar conclusion about the value of imaging in ocular Lyme disease. In their case, a 39-year-old male park ranger experienced posterior scleritis after several tick bites with erythema migrans.

Ultrasound and CT exams showed a large scleral mass (16 x 12 x 13 mm) in the patient, with painful proptosis in the left eye, as well as episcleral vascular dilation, reduction in bulbar motility, and chorioretinal folds in the upper temporal quadrant. They concluded that posterior scleritis should be added to the list of ocular manifestations associated with Lyme disease in order to ensure that proper corticosteroid treatment is given (Ophthalmology, January 2002, Vol.109:1, pp.143-145).

By Shalmali PalAuntMinnie.com staff writer

June 10, 2002

Related Reading

Orbital radiotherapy ineffective as treatment for Graves' ophthalmopathy, September 14, 2001

MRI lifts the lid on TRB, June 20, 2001

MRI algorithm envisions better look at the eyes, July 25, 2000

Copyright © 2002 AuntMinnie.com

.fFmgij6Hin.png?auto=compress%2Cformat&fit=crop&h=100&q=70&w=100)

.fFmgij6Hin.png?auto=compress%2Cformat&fit=crop&h=167&q=70&w=250)