A soccer ball flies through the air across the field, closely watched by players aiming to strategically "head" it to their teammates. Focused on the game, the players may not realize that heading the ball puts them at risk for mild traumatic brain injury, or as it is more commonly called, concussion.

A known risk in many sports, concussion is a major injury concern in soccer, according Dr. Sandy Glasson, orthopedic surgeon in Virginia Beach, VA, and physician for the women's U.S. team. She's worked with USA Soccer since 1992.

"I see it a lot on the national team," Glasson said. "And in the high school arena, I see more concussions in soccer than I do in football."

Whether that higher injury rate is due to "heading" the ball -- hitting it with one's head -- is the subject of some debate. But in a sport in which head injuries also occur when players collide with the ground or each other, there are understandable concerns about the short- and long-term effects of concussion.

"A lot of it is initial management, determining the level of the concussion and how long to keep the player out," Glasson said, citing a decision that begins on the field.

For more serious bumps, "I have a pretty low threshold for sending someone to the neurologist and getting an MRI. I do it for anything worse than a grade 1 concussion," she said.

A grade 1 concussion involves no loss of consciousness, only transient confusion that lasts less than 15 minutes. A grade 2 concussion also has no loss of consciousness, but symptoms of confusion or mental status abnormalities, including amnesia, last more than 15 minutes. Any loss of consciousness makes it a grade 3 concussion, according to the practice parameters developed by the American Academy of Neurology (Neurology, March 1997, Vol. 48:3, pp. 581-585).

Recovery from a mild concussion often occurs gradually over three months, according to the literature.

"However, evidence from both clinical and basic science investigations suggests that TBI (traumatic brain injury) can result not only in persistent or long-term neurologic deficit, but also continued decay months to years after the original trauma," the authors wrote based on a 2002 study from the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia.

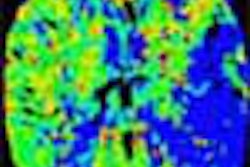

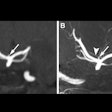

Radiologist Dr. Robert Grossman and colleagues set out to quantify brain atrophy one year after initial imaging in patients who suffered a mild or moderate traumatic brain injury (American Journal of Neuroradiology, October 2002, Vol. 23:9, pp. 1509-1515).

Imaging was performed on a 1.5-tesla unit with a quadrature transceiver-receiver head coil. Whole-brain dual fast spin-echo images (TR/TE, 2700/16 and 80; echo-train length, 8) with a 22-cm field of view, a 256 x 192 acquisition matrix, and axial section thickness of 3 or 5 mm from the base of the skull to the vertex, were obtained from subjects in the supine position.

When measured against a control group that hadn't experienced brain trauma, the subjects who were imaged at the time of injury (before they were part of the study) demonstrated a measurable loss of total brain volume and cerebrospinal fluid. The patients who lost consciousness at the time of injury showed the largest deficiencies.

"Our data provide evidence that brain volume decreases after mild or moderate brain injury, presumably as a result of cellular loss, and that patients with LOC (loss of consciousness) have a greater loss in volume," the authors concluded.

"However, the biologic reasons for and the clinical consequences of this atrophy remain to be defined," they wrote. "The measurement of neuronal loss with proton spectroscopy, whole brain N-acetylaspartate methods, neuropsychological assessment, and the tracking of clinical markers over months to years after injury could provide valuable clues to the consequences of atrophy in mild or moderate TBI."

By Matt King

AuntMinnie.com contributing writer

August 29, 2004

Related Reading

Brain damage in boxers occurs long before symptoms, November 15, 2002

Imaging is rarely definitive in concussion, February 21, 2002

Diffusion-weighted MRI useful in evaluating pediatric head trauma, October 3, 2001

fMRI could be instrumental in long-term study of head trauma, December 2, 1999

Copyright © 2004 AuntMinnie.com