The current movie Crash takes a close look at contemporary race relations. In one scene, a Caucasian woman tenses up and tightens her grip on her husband's arm as they walk closer to two African-American men. The implication, of course, is that she feels threatened by them and seeks the protection of her spouse -- or at least that is how the young black males perceive her actions.

A variety of factors -- such as environment, education, family background, history, and current events -- help determine how we each feel about, and react to, people of different ethnicities. These factors are closely tied to a neurological reaction that may determine our emotional response to race -- whether we are conscious of it or not. A number of recent neuroimaging studies have investigated the connection between our brains and race processing.

While these studies focused specifically on African Americans and Caucasians, the results will no doubt have broader implications, according to Jennifer Eberhardt, Ph.D., an assistant professor of psychology at Stanford University in Stanford, CA. Eberhardt recently authored a review on the current state of neuroscience and race relations.

"Researchers now treat race as a concept that can trigger a set of physical states within the self rather than as a concept that simply describes the physical traits of others.... Researchers highlight the ideas people have about race and the material consequences of those ideas," she wrote. "Neuroimaging techniques allow researchers to view the process by which those ideas become material -- the process by which ideas produce physical changes in individuals and thus come to shape who those individuals are" (American Psychologist, February-March 2005, Vol. 60:2, pp. 181-190).

White flight?

The amygdala is involved in sensing, relaying, and learning about potential danger. The act of stereotyping is a low-energy, easy way for humans to assess a person -- based on factors such as race, gender, and age -- without having to engage in social interaction. So does the amygdala influence the way we stereotype, or does stereotyping trigger some effect in the amygdala? Researchers from Princeton University set out to answer that question with functional MRI (fMRI).

"Individual differences, stimulus context, and social goals all influence relatively automatic biases," explained Mary Wheeler, Ph.D., and Susan Fiske, Ph.D. "We asked whether a person's conscious social goals can influence the process of person perception even at early stages indexed by activity patterns in the amygdala. Such results would demonstrate that goals control prejudice even earlier than often implied" (Psychological Science, January 2005, Vol. 16:1, pp. 56-63).

Fiske is from the department of psychology at New Jersey-based Princeton University, as was Wheeler at the time of the study. She is now with Ariston Pharmaceuticals in Framingham, MA.

Under fMRI, amygdala activity was compared in seven Caucasians during the presentation of pictures of unfamiliar African-American and white faces during three tasks:

- A socially neutral task in which the subjects were asked to simply identify a dot on face

- A social categorization task in which the subjects affirmed whether the person in the photo was over the age of 21

- A social individuation task in which subjects were asked whether the person would like a particular vegetable based on his or her looks

Scans were performed on a 1.5-tesla unit (Signa, GE Healthcare, Chalfont St. Giles, U.K.) with a radiofrequency head coil. The imaging sequence included T1-weighted spin-echo oblique axial slices, oblique axial functional slices, and a gradient-echo one-shot spiral trapezoidal pulse sequence. A voxel-wise mixed effects analysis of variance (ANOVA) isolated a "race-of-face main effect in the right amygdala and hippocampus and an interaction of the race-of-face by task in the right amygdala."

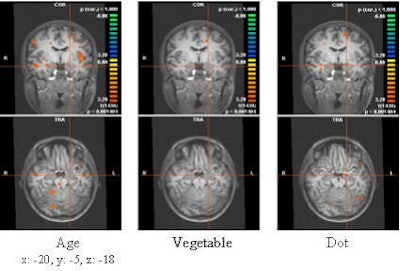

|

| Functional MRI data from nine white subjects, who either read the name or saw a picture of a vegetable. The activations are the result of a subtractive contrast analysis (activation to black faces minus activation to white). The amygdala activation in the age (categorization) task is bilateral. The dot activation is not in the amygdala, but the parahippocampal-amygdala junction. The coordinates at the bottom are Talairach coordinates. Image courtesy of Lasana T. Harris and Susan Fiske, Ph.D., from unpublished data. |

Fiske and Wheeler found that across the three tasks, the amygdala complex demonstrated a clear difference on fMRI in relative response to white versus black faces. During the social categorization task, there was a significant difference in left amygdala activity and some difference in the right amygdala during the presentation of white and black faces. During the social individuation task, activity in the right amygdala was suppressed.

In a second experiment, 45 subjects were shown the same photos and asked to match the pictures with a series of words associated with African-American stereotypes ("lazy," "athletic," "aggressive," "rhythmic").

"The presentation of black faces primed stereotype knowledge about blacks only when participants were processing the faces categorically," during the second task. However, during the first and third task, "the presentation of black faces did not significantly speed the response time to identify stereotype-relevant words," the authors wrote.

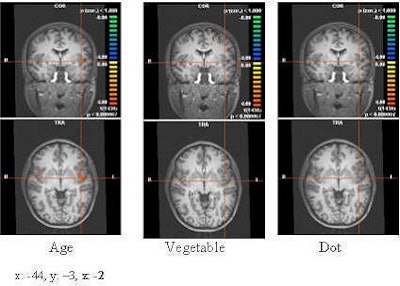

|

| Functional MRI insula activation present only for the age task in the left hemisphere, none of the others. Image courtesy of Lasana T. Harris and Susan Fiske, Ph.D., from unpublished data. |

They drew two main conclusions from this study: that simply looking at a black person did not automatically trigger a response in the amygdala of white subjects. Instead, black faces elicited greater amygdala activation than white faces only if the subjects were asked to socially categorize the faces, bolstering their initial hypothesis that an individual's experience influences prejudice on the most basic emotional level.

In an e-mail to AuntMinnie.com, Fiske stated her group has replicated the results from this study and will continue to expand on it. "We are exploring varieties of prejudices toward different types of out-groups, some of which appear to have unique neural signatures," she wrote.

Fear of a black planet?

Fiske and Wheeler's study built on previous work by Elizabeth Phelps, Ph.D., at New York University in New York City. Five years ago, Phelps and colleagues' fMRI-based study was the first to show that black and white social groups can evoke differential amygdala activity and that the activity is related to unconscious social evaluation.

"Unless one is socially isolated, it is not possible to avoid acquiring evaluations of social groups," Phelps' group wrote. "Having acquired such knowledge, however, does not require its conscious endorsement. Yet such evaluations can affect behavior in subtle and often unintentional ways" (Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience, September 2000, Vol. 12:5, pp. 729-738).

Phelps stated that data still need to be collected on race bias within the same race group -- i.e., how do black subjects react to other black people? Matthew Lieberman, Ph.D., and colleagues decided to answer that question using fMRI to study amygdala response in African Americans and Caucasians.

"Most previous studies have not directly addressed ... the issue of whether African-American and Caucasian-American individuals produce similar or different amygdala responses to African-American and Caucasian-American faces," wrote Lieberman's group in Nature Neuroscience (May 8, 2005).

Lieberman is from the department of psychology at the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA). His co-authors are from UCLA's Brian Mapping Center and the University of Pittsburgh.

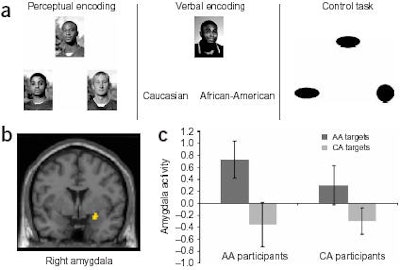

Their study included 11 Caucasians and nine African Americans. As with the previous study, the subjects took part in three tasks:

- A perceptual encoding task in which they selected a face from a pair that matched the target face based on race

- A verbal encoding task in which the subjects selected a race label that described the target face

- A control task in which the subjects matched shapes

Images were acquired using a 3-tesla scanner. The MR protocol included structural T1-weighted echo-planar scans and functional asymmetric spin-echo scans. The data were analyzed with statistical parametric mapping of the left and right amygdala, as well as the whole brain.

|

| Two-dimensional (above) and 3D (below) MR images of the region of amygdala that is more active for both African Americans and Caucasian Americans when looking at African-American photos, as compared to Caucasian-American photos. Images courtesy of the Social Cognitive Neuroscience Laboratory and Matthew Lieberman, Ph.D. |

|

In the whole-brain analysis, white participants produced greater amygdala activity to black targets than to white ones. Additionally, the ventromedial prefrontal cortex, the hippocampus, and the midbrain in the area of the substantia nigra were more active in response to black faces than white faces.

But in an interesting twist, the researchers found that both groups produced a greater response in the right amygdala to black targets than to white ones. During perceptual encoding, African-American participants produced greater amygdala activity to black targets than white ones.

"The present study suggests that amygdala activity typically associated with race-related processing may be a reflection of culturally learned negative associations regarding African-American individuals," they wrote.

|

| Task and amygdala responses. (a) Sample stimuli from the perceptual encoding task, the verbal encoding task, and the control task. (b) The region of right amygdala that was more active during the presentation of African-American faces than during the presentation of Caucasian-American faces, across both participant races and encoding tasks. (c) Amygdala activity as a function of participant race and target race during perceptual encoding of African-American and Caucasian-American targets. Results are in terms of parameter estimates of signal intensity, relative to the control task, in ROI analysis of the right amygdala. Error bars represent standard error of measurement. Image courtesy of Matthew Lieberman, Ph.D., and Nature Neuroscience, May 8, 2005, figure 1, copyright 2005 by the Nature Publishing Group. |

Lieberman told AuntMinnie.com that his group was initially surprised by this result.

"We had originally thought that African Americans would show a greater response to Caucasian faces," he wrote in an e-mail. "Once we obtained our results, however, we found a couple of studies (one by Dr. Robert Livingston and one by Brian Nosek, Ph.D.) showing a similar result in behavioral (non-fMRI) studies. So it turns out that our results are consistent with previous work" (Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, July 2002, Vol. 38:4, pp. 405-413; Group Dynamics: Theory, Research, and Practice, March 2002, Vol. 6:1, pp. 101-115).

For the next stage of their research, Lieberman said his group will do additional work with an African-American population, specifically to determine whether demographic backgrounds, as well as exposure to discrimination, affect the pattern of activity seen in the first study.

"While we think the African Americans in our study were a normal sample, we do not yet know if individuals who grew up in all-black neighborhoods would show the reversed pattern of activity," he said.

Erasing racism

The neuroscience study of race is not a new undertaking. However, the field has come a long way. Back in the 19th century, researches would examine the physical differences among racial groups in a bald-faced effort to document the superiority of whites over blacks, Eberhardt pointed out.

Obviously, that's no longer the case and the introduction of fMRI into this area of research has promoted a greater understanding of how complex social processes in the brain can be matched to established theories regarding race relations.

Wheeler told AuntMinnie.com: "When I first designed my study (more than five years ago), there was almost no research into social behaviors using the new tool of fMRI. One of my main goals was to show that it's possible to measure, in the brain, distinct processes that result in the complicated social behaviors that had been widely observed in the social psychology behavioral literature."

Modern race-based imaging research still requires fine-tuning. Some critics have suggested that fMRI studies are biased by design -- that participants are exposed to the faces during each for so long, they are able to control their responses (Psychological Science, December 2004, Vol. 15:12, pp. 806-813).

However, Wheeler noted that in her study, the subjects were unaware that they were being vetted for a racial response. In addition, the fMRI experiments reflect the ever-shifting nature of our thoughts and reactions, both intentional and unintentional.

"You can think about the processing of the brain as waves at the seashore -- a continuous ebb and flow of activity -- and some waves flow back into others," she stated. "You may happen to look at one particular time in one particular place and see a wave peak and that shows up in fMRI as an area of 'activity.' At different times the same brain areas can be involved in different stages of thought processing, as well as affected by other processes in different ways."

More sophisticated fMRI techniques will certainly continue to advance this area of investigation. One potential outcome of this research is the ability to use the information in a clinical setting, such as interventions for negative race-based behavior (such as xenophobia and hate crimes).

"I think the behavioral work is more relevant to intervention programs. Social psychology has been studying prejudice for 80 years, and we actually know quite a lot about how to undermine prejudice," Fiske pointed out. "The most successful interventions include (a) cooperative intergroup contact, in the service of an important shared goal, (b) encouraged by authorities, (c) with pleasant outcomes, and (d) in more than superficial settings."

"Our neuroimaging data just suggest that the right social situation can change people's spontaneous emotional prejudices," Fiske explained.

By Shalmali Pal

AuntMinniel.com staff writer

May 27, 2005

Related Reading

Some people get delayed cancer care - studies, May 16, 2005

Risk factors explain racial breast cancer patterns, March 29, 2005

fMRI identifies link between alleles, amygdala in affective disorders, March 22, 2005

Fearful body posture tells others: run! November 16, 2004

Copyright © 2005 AuntMinnie.com