My mother and I have engaged in the same conversation so many times now, it's like a well-honed comedy routine. I wait patiently on the phone while she hems and haws over the one topic she wanted to discuss with me, but is simply unable to recall at that critical moment. Eventually she curses her forgetfulness, and swears that she'll start writing things down. In turn, I promise to remind her, the next time we speak, that she had something to tell me.

According to a new neuroimaging study, my mother's memory is not necessarily failing. Rather, she -- like many older people -- is losing her ability to filter out irrelevant information and focus on the matter at hand. Researchers in California came to this conclusion after using functional MRI (fMRI) to assess the impact of normal aging on a cognitive mechanism known as "top-down modulation," which supports memory and attention.

"Attention is a two-sided coin," explained lead author Dr. Adam Gazzaley, Ph.D., in an interview with AuntMinnie.com. "It involves both the ability to focus on what's relevant, as well as the ability to ignore what's irrelevant or distracting. What we see is that in younger adults, (there is) both enhanced brain activity for relevant (information) and suppression for irrelevant (information) in visual areas of the brain. The older subjects, while they enhance the same for the relevant, they don't suppress for irrelevant information. Based on their pattern of brain activity, it does not appear that they are ignoring what they should be ignoring."

Gazzaley and colleagues enlisted 16 older subjects, ages 60-77, and 17 younger subjects, ages 19-30. The older participants were described as "healthy, well-educated, and cognitively intact" (Nature Neuroscience, September 11, 2005).

The study was conducted by Gazzaley's group at the University of California, Berkeley. Gazzaley has since moved to the department of neurology at the University of California, San Francisco.

The subjects underwent MRI on a 4-tesla scanner (Inova, Varian Medical Systems, Palo Alto, CA) with a send-and-receive radiofrequency head coil. Functional data was obtained with a two-shot echo-planar imaging sequence that was sensitive to blood oxygen level-dependent (BOLD) contrast.

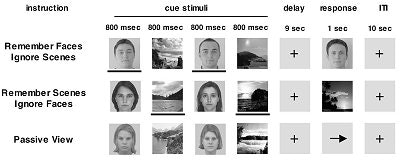

Imaging was done during three short-term memory experiments. Participants were shown randomized sequences of two faces and two natural scenes. During each task, they were instructed to ignore one stimuli, ignore the other stimuli, or passively view the images without attempting to remember either of them (see diagram of experiment below).

|

| Diagram courtesy of Dr. Adam Gazzaley, Ph.D. |

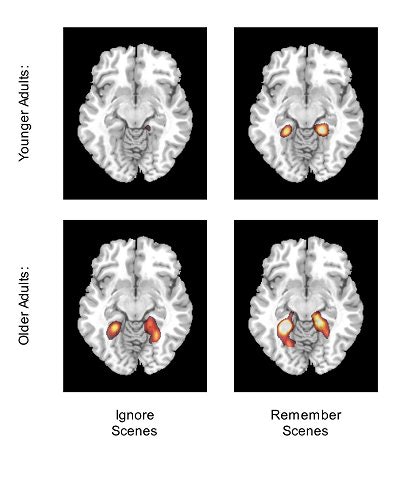

"Here we assessed age-related changes in top-down modulation using ... activity modulation within a scene-selective region of interest (ROI) in the left parahippocampal/lingular gyrus," the authors stated.

According to the results, when attempting to remember an image versus ignoring one, 88% of the older subjects demonstrated enhanced activity about the passive view baseline (versus 82% of younger subjects). However, only 44% showed suppressed activity (compared with 88% of the younger group), demonstrating an inability to suppress irrelevant information.

"These data suggest that older individuals are able to focus on pertinent information but are overwhelmed by interference from failure to ignore distracting information, resulting in memory impairment for the relevant information," they concluded.

|

| The top panels show lower activity in the scene-selective areas when a younger subject attempts to ignore the scenes versus remember the scenes. The lower panels reveal comparable activity in an older subject for both ignore and remember scene tasks, thus demonstrating the age-related suppression deficit. Image courtesy of Dr. Adam Gazzaley, Ph.D. |

"We found that the degree to which they failed to suppress the irrelevant information correlates with how well they remember the relevant information," Gazzaley added.

In addition, the older people exhibited reduced accuracy and a slower reaction time. But in a subgroup of six patients, who were at the older end of the age spectrum, the results were somewhat mixed.

Gazzaley explained that, as a population, the older subjects had impairment in their suppression ability and short-term memory. But on an individual basis, the top-down modulation in some of the patients in the subgroup was still intact, he said.

"That's something that is very interesting to us: Why are they doing well and what is their secret? We feel that somewhere in their brain activity or information about their lives there is a secret to what leads to successful aging," he said.

Gazzaley acknowledged that nutrition, physical activity, and other lifestyle issues may play a major role in why some seniors retain a stronger working memory, and that his group planned to evaluate those issues more closely in the future. Previous studies have indicated that physical activity can be associated with significantly better cognitive function and less cognitive decline in older people (Journal of the American Medical Association, September 22, 2004, Vol. 292:12, pp. 1454-1461).

He also explained how his group's results may ultimately be applicable to cognitive disorders, such as Alzheimer's disease and dementia.

"That's one of the directions that we're heading to from (the current study). We're starting with a population of patients with the diagnosis of mild cognitive impairment ... to see if they also have a suppression deficit," Gazzaley.

However, a better understanding of how memory correlates with aging does not have to be limited to those with serious cognitive disorders, he said.

"People live longer and there's no reason that in the last 30 years of your life you shouldn't be able to compete with younger people in the job market and maintain a normal lifestyle," Gazzaley said. "It's important to keep your cognitive abilities intact."

By Shalmali Pal

AuntMinnie.com staff writer

September 19, 2005

Related Reading

Daydreaming activity linked to Alzheimer's, August 25, 2005

A good night's sleep may be good for memory, June 15, 2005

Copyright © 2005 AuntMinnie.com