Intra-abdominal pregnancy is rare, but when it does occur, pinpointing it can be a complex process. Two case reports offer details on the role of imaging in making this difficult diagnosis.

In the first, Dr. Patama Promsonthi and Dr. Yongyoth Herabutya from Ramathibodi Hospital in Bangkok, Thailand, discussed the case of a uterocutaneous fistula that occurred after the placenta was left in a term abdominal pregnancy.

The patient was a 41-year-old woman who experienced massive hemorrhaging after the caesarean delivery of a baby from an undiagnosed abdominal pregnancy. According to the clinicians, "the amniotic sac was pressed against the anterior abdominal wall with the placenta attached to the posterior peritoneal surface and the uterine fundus" (European Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology and Reproductive Biology, June 26, 2006).

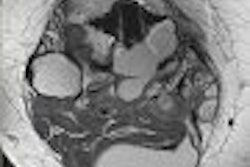

While a healthy female fetus was delivered, part of the placental tissue was separated and hemorrhaging ensued. Bleeding was controlled and the woman underwent laparotomy with the placenta and fetal membranes left in situ. A postoperative MRI of the abdomen revealed a large, extrauterine placenta inserting into the uterine fundus, the right lateral wall of the uterus, and the right fallopian tube. Transabdominal sonography revealed a large placenta (15 x 15 x 12 cm) attached to the uterine fundus.

The women returned to the hospital twice, complaining of fever, pain, and vaginal discharge. The first time, an anterior abdominal wall mass was discovered and it ruptured before planned drainage. On the second occasion, another MRI showed an encapsulated mass in the uterine fundus, which was connected to the anterior abdominal wall. The patient underwent subtotal hysterectomy, right salpingo-oophorectomy, and excision of the placental mass and fistula tract. She remained well during follow-up.

The authors highlighted two main take-home points from this case: First, decisions regarding the management of the placenta, and whether or not to remove it, should be based on multiple factors including placental location and bloody supply. Second, multiple imaging studies may be required to make the final diagnosis.

"If the placenta is left in situ, it may cause delayed hemorrhage, infection, and intestinal complications," they wrote. "Although sonography has long been an important diagnostic tool in obstetric practice, the diagnosis of abdominal pregnancy is often missed if unsuspected.... The abdominal MRI identified the size, the bloody supply, and the connection between the placental mass and the fistula tract."

In the second report, MRI and sonography were used in conjunction once again in abdominal pregnancy. The 28-year-old woman in this instance had a history of amenorrhea and pelvic inflammatory disease. She had previously undergone dilatation and curettage, as well as tuboplasty. Fertility treatment was used for her to successfully conceive.

An ultrasound at 12 weeks of gestation confirmed a single, intrauterine, normal pregnancy, according to Dr. Alka Karnik and colleagues at Dr. Balabhai Nanavati Hospital and Research Center in Mumbai, India.

During her pregnancy, the woman experienced a loss of consciousness and was treated for hypovolemic shock. The presence of free fluid was noted in her medical report. On the day she was admitted to Karnik's institution, the woman complained of exacerbated abdominal pain and a sudden increase in abdominal girth.

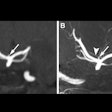

A sonogram was performed as the clinicians suspected that the sac and fetus were in an extrauterine location. On ultrasound, "a bulky, but empty uterus, measuring 14 cm in length was seen," the authors wrote. "Endometrial cavity could be traced and was empty. The fetus was seen in a thin-walled sac near the anterior abdominal wall, just above the fundus with no discernable myometrium around it, indicating an extrauterine pregnancy" (Journal of Women's Imaging, December 2005, Vol. 7:4, pp. 199-204).

An MR study confirmed the presence of a bulky, congested uterus with blood-filled endometrium in the pelvis and lower abdomen. The fetus was in lying transversely in the amniotic sac within the abdomen. On laparotomy, the placenta was partly in the abdominal sac and partly in the fundus. The dead fetus was extracted while the placenta was completely separated from the uterine fundus. Postoperative CT revealed no other abnormalities except for a bulky uterus.

The authors hypothesized that the woman's history of dilatation and curettage was a factor that predisposed her to rupture of the gravid uterus. In addition, her bout of hypovolemic shock may have ruptured the uterus near the fundus, but without dehiscence of the gestational sac.

The group cautioned that clinical symptoms of an abdominal pregnancy are nonspecific and even a sonogram may not offer any clues. Particular attention must be paid to the location of the myometrium with respect to the gestational sac, they advised.

"MRI can better show the defect in the myometrium," they wrote. "Due to newer ultrafast and breath-hold MRI sequences, it is now possible to scan ... despite fetal motion."

By Shalmali Pal

AuntMinnie.com staff writer

September 7, 2006

Related Reading

Ob/gyn ultrasound yields thorny legal issues, July 31, 2006

3D sonography of the endometrium adds value, May 5, 2006

Ultrasound helps identify adnexal mass as ectopic pregnancy, May 19, 2005

Copyright © 2006 AuntMinnie.com