The least athletic people in the world can still wind up with a "sports" injury -- skier's thumb (injury to the ulnar collateral ligament at the first metacarpophalangeal joint of the thumb), golfer's elbow (medial epicondylitis), swimmer's shoulder (impingement), and, of course, the dreaded athlete's foot.

Another "athletic" injury is tennis leg, generally described as a strain or rupture of the medial head of the gastrocnemius. It's often wrongly associated with garden-variety tendinitis or a tear in the plantaris tendon. And as with the other sports injuries, it can happen to people who are nowhere near a field, pitch, or court.

"The last tennis leg patient I saw was a woman who was hanging curtains," said Dr. Nancy Major, associate professor of radiology and surgery in the musculoskeletal division at Duke University Medical Center in Durham, NC.

"She was on a step ladder, went up on her toes, and felt this sudden pop in the back of her leg -- a classic finding of the plantaris rupture," Major explained.

Curtain-hangers aside, tennis leg generally takes down weekend warriors, particularly those who are involved in strenuous sports that may be beyond their physical capacity. Tennis leg often occurs while someone is lunging or pushing off one leg, and can feel like being kicked in the leg from behind. It's typically distinguished by an audible pop, and then pain radiating to the knee or ankle. Fluid accumulation is common and bruising can occur.

However the injury happens, MRI -- and ultrasound to some extent -- are important for making the definitive diagnosis. AuntMinnie.com checked in with musculoskeletal imaging experts for the lowdown on tennis leg.

Game, set, snap!

In a recent article, Dr. Hyo-Sung Kwak and colleagues described tennis leg as an "acute sports-related pain in the middle portion of the calf that is associated with a snapping sensation," usually incurred when "the muscle is overstretched by dorsiflextion of the ankle with the knee in full extension." This results in "simultaneous active contraction and passive stretching of the gastrocnemius" (Korean Journal of Radiology, September 2006, Vol. 7:3, pp. 193-198).

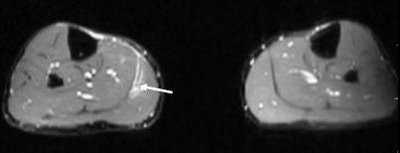

|

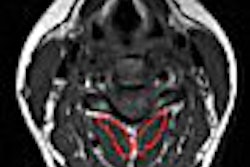

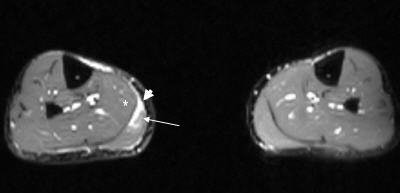

| Axial T2-weighted MR image of the legs shows increased signal in the medial portion of the right gastrocnemius muscle (white arrow) and fluid within the myofacial junction between the gastrocnemeius and the soleus (white asterisk) [Note: other leg is normal]. |

Kwak's group, from the Chonbuk National University Medical School in Chonju, Korea, labeled tennis leg as a "relatively common clinical condition," but general awareness of this injury is a different story.

"It's not something people have heard a lot about," said Dr. Douglas Beall in an interview with AuntMinnie.com. "I see a couple of cases a month. It's mostly amateur athletes, typically people in the age range of 35-55."

"It's very common in tennis, but also in other sports that require rapid lateral movement, like racquetball or soccer," added Beall, who is the director of radiology services at Clinical Radiology of Oklahoma and an associate professor of orthopedics at the University of Oklahoma, both in Oklahoma City.

|

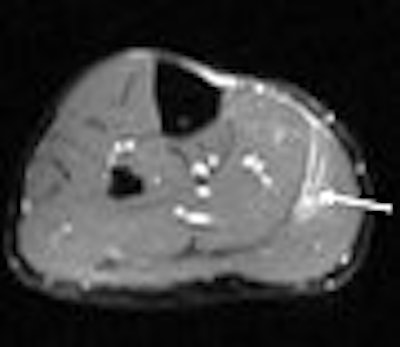

| Axial T2-weighted MR image of the legs obtained just superior to image above demonstrates increased signal within the gastrocnemius (white arrow) indicative of the tear of the medial head of the muscle. |

In 2001 the Australian Cricket Board videotaped and analyzed a left gastrocnemius strain in progress. It was sustained by a batter taking off to run and appeared to correspond to a sudden deficit in the gastrocnemius muscle while the player's entire body weight was on his left foot, and his center of mass well in front of the leg (British Journal of Sports Medicine, June 2002, Vol. 36:3, pp. 222-223).

In a 2002 article in Radiology, Dr. Gonzalo Delgado and colleagues pointed out that "for several years, tennis leg was attributed to a rupture of the plantaris tendon. More recently, most investigators have implicated a rupture of the medial head of the gastrocnemius muscle at the musculotendinous junction in the pathogenesis of this entity. Some authors still question the role of the plantaris tendon in tennis leg," (Radiology, July 2002, Vol. 224:1, pp. 112-119).

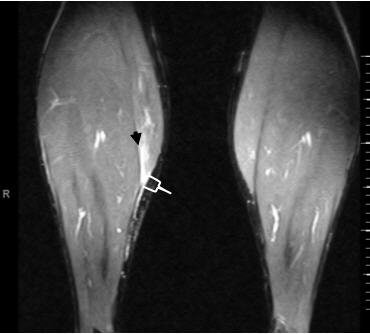

|

| Coronal T2-weighted MR image of the legs shows the fluid in the myofascial junction (black arrowhead) as well as slight proximal retraction of the medial head of the gastrocnemius muscle from its musculotendinous junction (white bracket). Images courtesy of Dr. Douglas Beall. |

Major concurred, noting that "in the orthopedic realm, there are people who find it a bit controversial as to whether plantaris tears actually occur," she said. "Some orthopedic surgeons think these are all gastrocnemius tears, and not related to the plantaris at all."

MRI serves accurate diagnosis

The most important role of imaging in tennis leg is to rule out more serious conditions, such as deep venous thrombosis. The trick is correctly deciding what part of the leg to image. Even those who agree that tennis leg is a calf injury don't necessarily concur on what part of the calf or what serves as the best imaging angle. This can often cause some problems for radiologists when they receive an imaging request from a referring physician.

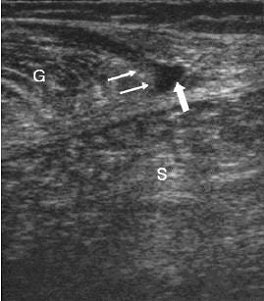

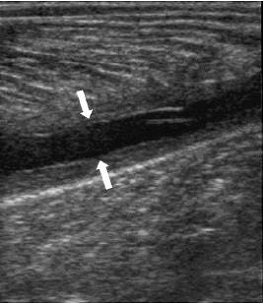

|

A 35-year-old male with a partial rupture of the medial head of the gastrocnemius at the musculotendinous junction. Top, the longitudinal US image shows the medial head of the gastrocnemius muscle with partial discontinuity of the muscle fibers (double arrows). A small hypoechoic fluid collection (single arrow) is noted. G = gastrocnemius muscle, S = soleus muscle. Below, the longitudinal US image one week later shows a hyperechoic fluid collection (arrows). This fluid can be considered as most likely representing flesh blood.

|

Dr. Douglas Mintz, a musculoskeletal radiologist for the Hospital for Special Surgery in New York City, told AuntMinnie.com that he considered "tennis leg (to be) more specific of the lower calf. We get orders sometimes that are a little bit general in what (referring doctors) are looking for: a little more proximal, or a little more distal, or the ankle or the Achilles."

While Kwak and colleagues stated that tennis leg occurred in the middle of the calf, Beall said he looked at it as an upper calf strain, which ultimately leads to confusion about the source of the pain. Certain knee problems can cause calf pain, he explained. Frequent misdiagnosis of tennis leg includes a Baker's cyst, a ruptured plantaris tendon or torn muscle.

|

| Same patient as above. The longitudinal image four weeks later shows the reparative process as a hypoechoic area (arrows) and a well-defined anechoic fluid collection. Kwak H, Han Y, Lee S, Kim K, Chung G, "Diagnosis and Follow-up US Evaluation of Ruptures of Medial Head of the Gastrocnemius ('Tennis Leg')," Korean J Radiol 7(3), September 2006. |

Beall has encountered the same problem as Mintz in terms of a general misunderstanding of where tennis leg occurs. "Unless doctors know (the problem) is in the calf, they tend to lump it into a knee exam. And by doing that, you can miss the tennis leg, because it'll be too far down to see on an MRI of the knee," he said.

However, there is agreement that MR is the imaging modality of choice, with ultrasound as a possibility for second-line imaging.

"It's a really easy diagnosis to make on MR," said Major. "What we see is a whole tubular, fluid-filled collection along the course of the plantaris tendon."

Beall and Mintz shared some of their MR tips for pinpointing tennis leg. "If we're confident that tennis leg is what is wrong, we'll use a knee coil -- an eight-channel one if we can -- (positioned at) where the patient feels the pain, and then do axial fat-suppressed images and axial high resolution," Mintz revealed. "Then we'll do that in the axial plane, and then either the coronal or the sagittal plane, or both. We use an intermediate TE for everything."

Beall also said he used axial and sagittal MRI images in an anatomic plane and a fluid-sensitive plane.

In their cadaver study, Delgado's group performed T1-weighted spin-echo MR imaging with a receive-only dedicated knee coil. Images of the specimens were obtained in the transverse, sagittal, and coronal planes and the transverse images were obtained from the metadiaphyseal region of the femur to the calcaneus.

Alternatively, Kwak's group has chosen to work with ultrasound for assessing tennis leg. In their 22-patient tennis leg study, they found axial ultrasound valuable for differentiating partial lesions from complete lesions in the medial head.

Mintz said he has occasionally found ultrasound helpful "because you can just put the probe right where the patient has symptoms, and you can look at the hematoma traveling all the way up the knee if you need to."

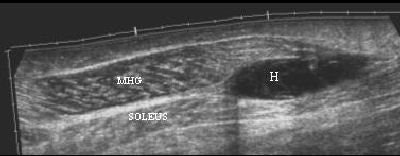

|

| Tennis leg-related hematoma on ultrasound. Image courtesy of Dr. Ronald Adler, Hospital for Special Surgery, New York City. |

Beall agreed with Mintz, adding that sonographic evaluation of the gastrocnemius complex was useful if fluid was present or if the hematoma could be seen in the middle of the muscle.

But ultrasound should be used with caution, according to Major. "When there's hemorrhage present, it often doesn't look like a simple fluid collection (with ultrasound) and it has mixed echoes in it, so it can be a less straightforward diagnosis than with MRI," he said.

On the ball rehab

As vital as appropriate MR imaging is to diagnosing tennis leg, it has yet to take on a major therapeutic role. On the other hand, the quicker the diagnosis is made, the faster the recovery. In the Kwak study, two patients were asymptomatic until two weeks after injury, and one showed delayed fluid collection, leading the authors to conclude that the sooner a diagnosis was made, the better the prognosis.

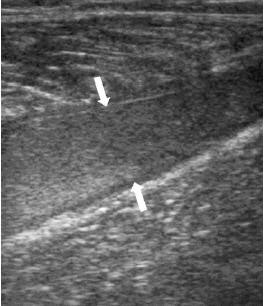

|

MR images of the tennis leg injury sustained by Mintz. Above, a coronal fat-suppressed image through the back of the calf with the arrow pointing to the muscle tear. The hematoma is tracking up the leg. Below, sagittal MR of the whole calf. Arrow points to the muscle tear and the white below it is the gap from the muscle retraction. Images courtesy of Dr. Douglas Mintz.

|

Tennis leg treatments range from the simple application of heat or cold to stretching and strengthening to cast and crutches. Beall recommended conservative therapy: rest, analgesics, and protected weight-bearing exercises. "Muscle will heal very well. You'd have to have a torn gastrocnemius complex -- a complete tear -- before surgical intervention is required," he said.

"There's really very little that you can do for tennis leg," Major agreed. "There's no way to fix it, but you do have to watch for some potential development of compartment syndrome, if there's a large amount of hemorrhage, for instance. When it's severe, fasciotomies are necessary to relieve the pressure on the neurovascular bundles. There isn't too much room in the leg for swelling. Therefore, the bundles become compressed."

Mintz seconded those opinions, and he would know, having suffered a tennis leg injury himself. "You treat the low-grade injury essentially the same way as the high-grade injury. Imaging of tennis leg is more to make sure that your diagnosis is correct, and to look for other pathologies."

By Sydney SchusterAuntMinnie.com contributing writer

January 2, 2007

Related Reading

Part I: Choosing between MR and US in musculoskeletal imaging, September 7, 2006

Young tennis players warned against overtraining, May 19, 2006

Just (over) do it! Imaging pegs overuse injuries in specialty sports, October 8, 2003

Copyright © 2007 AuntMinnie.com