In an article last year, Australian radiologists asserted that MRI was unnecessary for estimating the duration of rehabilitation of an acute hamstring injury in professional athletes. In a subsequent commentary, Dr. Alison Sponge of the University of Western Ontario in London, Canada, praised the group results as "refreshing," because it championed the "increasingly lost art of a high-quality clinical examination ... in an era (dominated) by advanced imaging technology" (American Journal of Sports Medicine, June 2006, Vol. 34:6, pp. 1008-1015; Clinical Journal of Sports Medicine, January 2007, Vol. 17:1, pp. 81-82).

While the clinical exam is certainly the cornerstone of injury assessment, two newer studies affirm the major role MR plays in defining hamstring injuries. First, Australian and British researchers evaluated whether MR features of a strain can assist in risk stratification for reinjury. Then, Swedish sports medicine specialists looked at hamstring strains during slow-speed stretching. While MR results didn't hold all the answers, the imaging exam was still worth performing, according to the experts.

Caution: ACL reconstruction zone

Dr. George Koulouris and colleagues enrolled 41 Australian rules footballers who had sustained hamstring injuries (10 had recurrent injuries during the study period). Symptoms included the onset of posterior thigh pain or stiffness and the inability to train or play.

Koulouris is from Victoria House Hospital in Melbourne, Australia. His co-authors are from institutions in London and Victoria, Australia. MRI of hamstring injuries has been an ongoing focus for the group.

For this research, imaging was done on a 1.5-tesla unit (Sigma LX, GE Healthcare, Chalfont St. Giles, U.K.) using a phased-array surface coil on the thigh and centered on the region of maximal tenderness. Those who sustained a reinjury were imaged twice. Sequences included axial and coronal oblique fast spin-echo (FSE) imaging, as well as axial and coronal oblique FSE inversion-recovery imaging. Two musculoskeletal radiologists read the images and came to a consensus on the injured area (longitudinal length and cross-section).

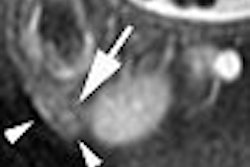

"An acute injury was considered to be present if abnormal increased signal intensity on the fluid-sensitive sequences was detected," they explained. "Changes in injury parameters between the first and second injury were analyzed using the Wilcoxon signed-rank test" (American Journal of Sports Medicine, April 17, 2007).

According to the results, 24 of 31 (74.2%) players with a first-time injury reported a history of hamstring strain. On the other hand, 100% of the 10 players with repeat injuries were positive for a history of strain. In addition, those who had previously undergone an anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) reconstruction (40%) had an association with reinjury within the same competition season, the authors reported. The hamstring strain occurred on the same side as the ACL surgery and may be related to hamstring tendon autograft, they hypothesized.

Those players with reinjuries had a mean injury length of 98.7 mm, compared to the 83.8 mm sustained by first-timers. Nine of the 10 players with repeat injuries also demonstrated muscle damage extending over 60 mm. This finding led the authors to suggest that "injuries > 60 mm in length should be managed with caution because such injuries appear to have a higher likelihood of restraining."

Dancers: So you think you can stretch

While football players may be more likely to sustain hamstrings injuries during high-speed running, slow stretching -- with the joint in an extreme position -- can also do damage, according to Swedish sports medicine specialists.

Physical therapist Carl Askling and colleagues enrolled 15 professional modern and classical dancers in their study, conducted at the Swedish School of Sport and Health Sciences, Karolinksa Institute, and Sophiahemmet Hospital, all in Stockholm. Radiologist Dr. Magnus Tengvar is a co-author.

The subjects confirmed a history of first-time, acute sudden pain from the posterior thigh. In addition, all 15 dancers reported that they sustained their injuries during a slow-speed stretching exercise -- 11 were in a sagittal split and four were in a side split.

All participants had clinical exams on four occasions, ranging from two days to 42 days after injury. MR studies were done at the same time for a total of four exams, on 1-tesla unit (Magnetom Expert, Siemens Medical Solutions, Erlangen, Germany). MR sequences included longitudinal, sagittal, and frontal STIR imaging, transverse T1-weighted, T2-weighted, and STIR imaging on both legs.

"A muscle was considered injured when it contained high signal intensity, as compared with the uninjured side, and a tendon was deemed injured if it was thickened and/or had a collar of high signal intensity around it on the STIR images," they wrote. The two independent readers also assessed the size of the injury based on length, width, and depth (American Journal of Sports Medicine, June 13, 2007).

According to the MR results, the semimembranosus muscle was injured in 87% of the cases, as was the quadratus femoris muscle (also 87%). Eleven of the 13 semimembranosus muscle injuries showed a collar of high signal intensity around the thickened tendon, the authors reported. After six weeks, MRI signs of injury still remained for 10 of these dancers.

Eleven of 13 quadratus femoris injuries showed intrafascial and extrafascial edema. After six weeks, MR injury signs remained for six subjects. In addition, one out of five adductor magnus injuries persisted over the long term. Finally, changes in length, width, and depth of sustained injuries ranged from 7% to 52% over six weeks.

"Even though the current injury is referred to as a 'hamstring strain,' it clearly involved more than just hamstring muscles," Askling's group wrote, noting in particular the injuries to the quadratus femoris, given that the anatomy is different than the semimembranosus muscle. One possible explanation for quadratus femoris injuries could be that the extreme hip movement and adduction at the end of a split, they hypothesized.

Recovery time from a slow-stretch hamstring injury could not be predicted based on the MRI parameters of length, width, and depth, the authors concluded. Also, because the effects of the injuries on the dancers were small, they ran the risk of returning to activity prematurely. But this type of strain can be serious and require attention, they stated. In this setting, MR can be used to confirm the specific muscle that is involved, with results playing a role in what is bound to be a prolonged rehabilitation.

By Shalmali Pal

AuntMinnie.com staff writer

July 13, 2007

Related Reading

From tears to TKA: The ins and outs of knee MRI, September 5, 2006

Focused exams suitable for some musculoskeletal US studies, March 26, 2006

The role of MRI and US in acute hamstring injuries: A preliminary report, July 22, 2002

Copyright © 2007 AuntMinnie.com

.fFmgij6Hin.png?auto=compress%2Cformat&fit=crop&h=100&q=70&w=100)

.fFmgij6Hin.png?auto=compress%2Cformat&fit=crop&h=167&q=70&w=250)