MRI is better than clinical assessment in determining breast tumor response to presurgical neoadjuvant chemotherapy, a finding that could help direct treatment for breast disease, according to new study published in the June issue of Radiology.

Researchers from the University of California, San Francisco (UCSF) found that MRI was better able to measure pathologic complete response and residual cancer burden prior to, during, and after chemotherapy in women with invasive breast cancer lesions 3 cm or larger (Radiology, Vol. 263:3, pp. 663-672).

Lead study author Nola Hylton, PhD, professor of radiology and biomedical imaging at UCSF, and colleagues believe that MRI's ability to gauge early response to treatment will allow physicians to alter inadequate care-management plans and eventually lead to better patient outcomes.

Hylton and colleagues reviewed data from the American College of Radiology Imaging Network (ACRIN) 6657 trial, the imaging component of the Investigation of Serial Studies to Predict Your Therapeutic Response With Imaging and Molecular Analysis (I-SPY) breast cancer trial. ACRIN 6657 is designed to evaluate MRI's ability to determine the response of primary breast cancer to chemotherapy. In addition, it is measuring the benefits of MRI for clinical assessment to predict response and risk of recurrence.

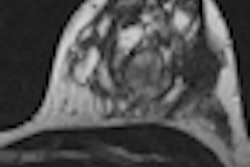

Researchers analyzed results from 216 women, ranging in age from 26 to 68, who underwent neoadjuvant chemotherapy between May 2002 and March 2006 for stage II or III breast cancer. MRI scans were performed on a 1.5-tesla system with a dedicated breast coil at four different time points: prior to treatment, after one round of chemotherapy, after a second cycle of therapy, and prior to surgery.

When chemotherapy was completed, 88 women (41%) showed complete clinical response, while 89 (42%) exhibited a partial response. Stable disease was reported in 17 patients (8%) and progressive disease was found in eight (3%). Clinical response data were not available for 14 patients (6%).

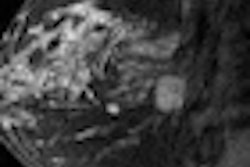

The mean size of residual disease found by MRI was 23 mm, ranging from 0 to 150 mm, among 208 patients for whom pathology was available.

MRI size measurements were superior to clinical examination at all time points, with tumor volume change showing the greatest relative benefit at the second MRI exam. MRI was better than clinical assessment in predicting both complete tumor response and residual cancer burden.

"Among MR imaging size measurements early in treatment, volume estimates are superior to diameter estimates for predicting pathologic outcomes," Hylton and colleagues concluded. "For prediction of [pathologic complete response], the greatest relative advantage in predictive ability occurs early in the treatment," with tumor volume change showing the greatest relative benefit at the second MRI exam.

The researchers also noted that MR images help to define the size of the tumor and its biological activity, while water diffusion measurements through MRI provided an indirect reflection of cancer cell density.

Hylton and colleagues are currently evaluating I-SPY data to see if MRI can better predict the likelihood of breast cancer recurrence. They expect to publish those results later this year.