Researchers using diffusion-weighted MRI to screen children with sickle cell anemia have found that acute silent cerebral ischemic events occur more frequently than previously thought, and a child with sickle cell anemia is at constant threat of ischemia.

The study from Cincinnati Children's Hospital Medical Center detected acute silent cerebral ischemic events in 10 scans (1.3%) of 652 children, with an incidence rate of 47.3 events per 100 patient-years.

The study, led by Dr. Charles Quinn from the hospital's department of hematology and published online October 29 in Archives of Neurology, concluded that these children could very well experience ongoing cerebral ischemia.

Sickle cell anemia can prompt recurring episodes of ischemia and is the most common cause of overt stroke in children, the researchers noted. Transcranial Doppler ultrasonography's ability to direct therapy can decrease the frequency of overt stroke, but silent cerebral infarction can still occur and is more common.

Silent cerebral infarction in children is associated with neurocognitive impairment, poor performance in school, and increased risk for subsequent overt stroke. MRI can detect and quantify the results of critical cerebral ischemia, which is the combination of stroke and silent cerebral infarction in the brain.

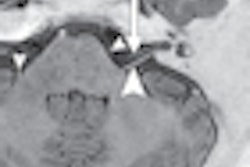

A silent cerebral infarction is an infarctlike lesion that can be seen on MRI and helps provide additional information on an abnormality on a neurologic examination that cannot be explained by the location of the infarctlike lesion. Quinn and colleagues used prior research to define an infarctlike lesion as an abnormality at least 3 mm in size that was visible on at least two MR images.

To calculate the frequency of acute silent cerebral ischemia, the researchers reviewed 771 diffusion-weighted MRI results from 652 children with a mean age of 9.5 years. Those scans provided 21.1 patient-years of observation. The estimated incidence of acute silent cerebral ischemic events was 47.3 events per 100 patient-years based on all diffusion-weighted MRI results.

Eleven children had evidence of acute ischemia in diffusion-weighted MRI-positive lesions. One patient had a clinically overt stroke and was excluded from the analysis. The remaining 10 cases were silent cerebral infarctions, eight of which were found via screening MRI scans and two infarctions were on prerandomization MRI exams.

The frequency of acute silent cerebral ischemic events was not different between the screening and prerandomization MRI groups if considered separately, the authors noted.

New or enlarged silent cerebral infarction occurred in eight participants in the study. New silent cerebral infarctions were found in five patients, with two having an enlarged lesion and one having both a new and enlarged lesion. Thus, the incidence of new or enlarging silent cerebral infarction was 10.7 events per 100 patient-years.

The incidence of acute silent cerebral ischemic events was statistically significantly higher than the incidence of progressive silent cerebral infarction, the authors concluded.

"In this largest prospective study to date in [sickle cell anemia (SCA)], to our knowledge, we have provided evidence that clinically silent cerebral ischemia can be detected acutely, and that [acute silent cerebral ischemic events (ASCIEs)] occur in asymptomatic children without concurrent or antecedent illness," Quinn and colleagues wrote. "Moreover, ASCIEs appear to be four times more frequent than progressive [silent cerebral ischemia (SCI)]."

Based on the results, the researchers concluded that asymptomatic children with sickle cell anemia experience cerebral ischemia far more frequently than previously recognized.

"By considering only discrete, easily visualized, and permanent brain lesions (stroke and silent cerebral infarction), one underestimates the true frequency of all ischemic insults to the brain in sickle cell anemia," the authors added. "We propose that the brain in sickle cell anemia is at constant threat of ischemic injury."

They recommended additional research to better understand the causes, consequences, and treatment options of acute silent cerebral ischemic events in sickle cell anemia.