Researchers at George Washington University in Washington, DC, have developed a functional MRI (fMRI) technique that reveals what could be a valuable biomarker to evaluate brain function in boys with autism spectrum disorder.

The fMRI approach, detailed online April 20 in JAMA Psychiatry, targets oxygen levels and oxygen utilization across different brain regions to identify areas of activity, or lack thereof, when children with autism spectrum disorder are given a certain task.

Kevin Pelphrey, PhD, from George Washington University.

Kevin Pelphrey, PhD, from George Washington University."By looking at that, we can determine where neuro activity is taking place," said co-author Kevin Pelphrey, PhD, director of the university's Autism and Neurodevelopmental Disorders Institute. "It tells us about actual activity associated with particular types of thinking, behavior, and perception."

Gender disparity

Children with autism spectrum disorder are unable to neurologically process the difference between the movement of human and nonhuman objects. This behavioral and social deficiency, which affects four times as many boys as girls, can stay with these children into young adulthood.

The current study stems from previous research by Pelphrey and colleagues published in The Neurobiology of Childhood in January 2014. They discovered evidence of a brain region that appears to develop differently in children with autism spectrum disorder compared to those who progress normally.

This particular brain network is involved in social information processing that helps individuals distinguish between people and objects and between biological and nonbiological motion.

Until now, functional MR has not been a standard part of the treatment for autism spectrum disorder.

"In most cases, kids with autism will get a structural MRI scan, which tells us about the structure of the brain and uncovers gross abnormalities," Pelphrey told AuntMinnie.com. "We are interested in finding activity in brain regions that are known to process social information, and functional MRI gives us the ability to do that with very tight resolution."

The task at hand

Researchers enrolled a total of 114 young people ranging in age from four to 20 years old; among them were 82 boys. There were 57 boys and girls with autism spectrum disorder. The other 57 subjects were healthy controls with normal development.

Participants were told to watch a video of "point-line walkers" while they were being imaged on a 3-tesla MRI scanner (Magnetom Tim Trio, Siemens Healthineers). These walkers had small reflective stickers affixed to their major joints, and their movements were filmed under a special light that accentuated the bright points. Through this process, study participants were given the sense of a person moving without being able to see the walker's entire form.

"The technique provides a strong social perception of someone trying to interact with another person, which, in this case, would be the study subject," Pelphrey explained.

The participants also saw a scrambled version of that same video whereby the same reflective dots were moving, but the viewer could not tell specifically what the reflective points were doing.

"So you have a social versus a nonsocial movement," he said. "That beautifully activates a whole set of brain regions involved in processing social information. The kids don't mind watching it. It's not the most exciting thing, but it is not boring either."

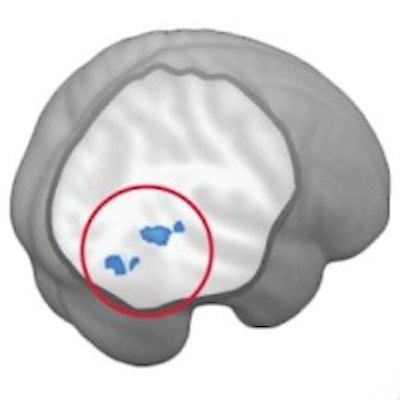

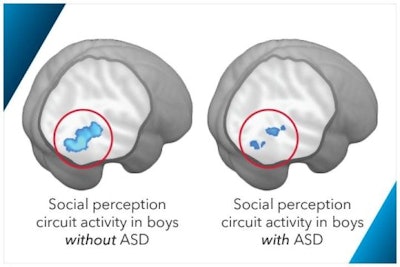

Based on the fMR images, the activated regions of the brain are in the temporal lobes and the frontal lobes, which become the biomarkers and can be used to help assess the level of autism, its severity, and potentially whether or not treatment could be beneficial.

Functional MRI illustrates brain regions affected by autism spectrum disorder. Image courtesy of George Washington University.

Functional MRI illustrates brain regions affected by autism spectrum disorder. Image courtesy of George Washington University."We are now able to go through every small voxel of the brain and pixel of the images and say: Is this part of the brain useful or not in terms of identifying autism versus typical kids?" Pelphrey said.

Boys vs. girls

In fact, the fMRI technique was able to distinguish between boys with and without autism spectrum disorder at a sensitivity and specificity rate of 76% each.

There was, however, no difference in the results for girls with and without autism, reinforcing the knowledge that this area of brain functions differently between boys and girls beyond what is already known about gender differences with autism.

"The question has been: Why is that? Are boys more susceptible to all neuro development and neuropsychiatric disorders?" Pelphrey said. "Or is it girls who have some sort of built-in, defensive compensatory brain developmental processes that help protect them from autism?"

To explore this issue, the researchers plan to expand their study to enroll a larger number of boys and girls to see if the fMRI technique can be modified for girls.

The group is implementing a behavioral treatment for autism spectrum disorder that is known to work in relieving symptoms, and they hope to see how it affects this biomarker to potentially determine which kids will benefit from treatment.