MRI scans have identified an area of the brain associated with a rare form of dementia that allows affected patients to comprehend written words but prevents them from understanding spoken words, researchers reported in the March issue of Cognitive and Behavioral Neurology.

The condition, known as primary progressive aphasia, infiltrates the superior temporal gyrus. The fact that this rare neurodegenerative disease is associated with a clinical language disorder is a unique finding.

"It doesn't happen that often that you just get an impairment in one area," said senior author Sandra Weintraub, PhD, a professor of psychiatry and behavioral sciences and neurology at Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine, in a statement. "The fact that only the auditory words were impaired in these patients and their visual words were untouched leads us to believe we've identified a new area of the brain where raw sound information is transformed into auditory word images."

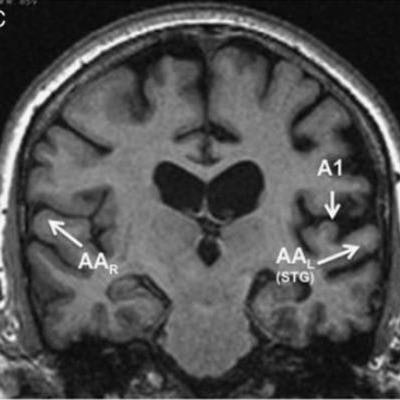

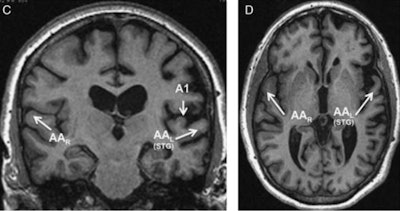

MRI scan from one of the four patients in the study, which linked auditory deficiencies to the superior temporal gyrus in the left hemisphere. Images courtesy of Northwestern University.

MRI scan from one of the four patients in the study, which linked auditory deficiencies to the superior temporal gyrus in the left hemisphere. Images courtesy of Northwestern University.As an example of primary progressive aphasia, if patients in the study saw the word "hippopotamus" written on a piece of paper, they could identify a hippopotamus on flashcards. However, when patients heard the word "hippopotamus," they could not point to the picture of the animal.

The four patients in the study displayed the same inability to understand words they heard, compared with words they read. They also had greater difficulty in naming objects verbally than in writing (Cogn Behav Neurol, March 2019, Vol. 32:1, pp. 46-53).

"These features of language impairment are not characteristic of any currently recognized primary progressive aphasia variant," the researchers wrote.

Through MRI, they found the deficiencies were centered in the superior temporal gyrus of the brain's left hemisphere, which is associated with auditory function.

Approximately 30% of primary progressive aphasia cases are the result of molecular changes in the brain due to Alzheimer's disease, but the most common cause is frontotemporal lobar degeneration (FTLD). All four subjects in this study had FTLD transactive response DNA-binding protein Type A (TDP Type A); three diagnoses were confirmed postmortem, while one person's condition was surmised based on a granulin gene mutation.

The findings are preliminary, but Weintraub and colleagues hope the results will prompt more research involving primary progressive aphasia patients in the future.

"From a practical point of view, the identification of these features in patients with primary progressive aphasia should help in the design of therapeutic interventions where written communication modalities are promoted to circumvent some of the oral communication deficits," they concluded.