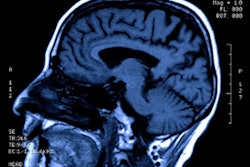

Brain maps based on functional MRI (fMRI) scans are proving useful in predicting the spread of brain atrophy that leads to progressive dementia, according to a study published October 14 in Neuron.

Researchers from the University of California, San Francisco (UCSF) used these fMRI maps to pinpoint "epicenters" of dementia-related activity, or lack thereof, by comparing connectivity patterns of brain regions to baseline atrophy observations. From that data, they created a statistical model to predict the future spread of atrophy to other parts of the brain.

"These findings provide novel, longitudinal evidence that neurodegeneration progresses along connectional pathways and, further developed, could lead to network-based clinical tools for prognostication and disease monitoring," wrote the authors, led by Jesse Brown, PhD, an assistant professor of neurology at the UCSF Memory and Aging Center.

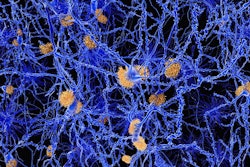

Neurodegenerative diseases can spread throughout the brain through network connections. The ability to predict their destructive, progressive path is a challenge, however. Knowing how neurodegeneration spreads could lead to new clinical methods to determine the success of treatments or perhaps to stall disease process altogether, according to the study authors.

"The central assumption of our connectivity-based prediction approach is that disease pathology spreads directly between anatomically connected brain regions," they wrote.

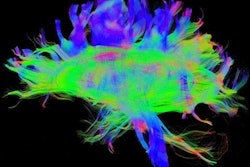

To test this hypothesis further, Brown and colleagues began with fMRI scans of 75 healthy adults to build maps of functional patterns of 175 different brain regions that best matched the atrophy patterns in patients' baseline results.

"Using these maps, we then identified each patient's epicenter, defined as the region whose intrinsic connectivity map in [healthy] controls most strongly resembled the patient's atrophy map," the authors explained.

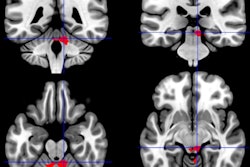

The researchers then recruited 42 patients with the behavioral variant frontotemporal dementia, which adversely affects a person's social behavior, and semantic variant primary progressive aphasia, a form of the dementia that severely reduces a person's language skills. Each subject underwent a baseline fMRI scan to assess the extent of existing brain degeneration and then a follow-up fMRI exam approximately 12 months later to measure how the disease had progressed. By doing so, the researchers were able to estimate where the atrophy initially began, such as the epicenter, and then see how and where the disease spread to other connected brain regions.

Baseline and follow-up fMRI comparisons discovered two measures that significantly improved predictions of a brain region's eventual atrophy. One indicator is the "shortest path to the epicenter," which is based on the distance between the atrophied epicenter to a nearby brain region beginning to show the effects of the disease. The other important variable is a "nodal hazard," which represents the number of brain regions connected to another region where significant atrophy already exists.

The "shortest path" finding suggests that the epicenter regions "may have slowed their rate of change due to an atrophy 'ceiling' effect, where substantial previous atrophy has left little remaining gray matter available to lose, at the same time that epicenter neighbors showed peak change," Brown and colleagues wrote. As for the second key finding, regions with a higher nodal hazard showed greater longitudinal atrophy.

"Using these predictors and baseline atrophy, we could accurately predict longitudinal atrophy in most patients," the authors added. "The regions most vulnerable to subsequent atrophy were functionally connected to the epicenter and had intermediate levels of baseline atrophy."

As for improving upon this predictive model, Brown and colleagues suggested the next step will be to use patients' functional and anatomical connectomes to evaluate how the disease relates to changes in connectivity and advance the spread of atrophy.