A new study published online November 19 in Cell Reports sheds new light on how some people are able to recover from hemispherectomy -- removal of half their brain -- and still function at a high level. Functional MRI (fMRI) demonstrated how the brain compensates by restoring communication in certain areas to compensate for the loss.

In short, the remaining hemisphere evolves to create stronger connections within brain regions to perform daily functions, such as vision, movement, and cognition, as if the brain were whole. In many cases, the remaining hemisphere easily outmatches the function of brain networks in normal adults.

"The current study provides evidence on the neural reorganization that produces compensated cognition after the surgical removal of one hemisphere," wrote the authors, led by Dorit Kliemann, PhD, a postdoctoral researcher at the California Institute of Technology. "Functional connectivity of the human brain, as measured with resting-state fMRI, leaves open exciting future questions for task-based functional localization in hemispherectomy. Insights from these rare patients argue that intrinsic mechanisms of brain organization in only half of the typically available cortex can be sufficient to support extensive cognitive compensation."

Firing on all cylinders

Healthy people naturally have brain networks that fire on all cylinders to handle daily thoughts, physical function, and behavior. Not everyone, however, is that fortunate.

Hemispherectomy is a neurosurgical procedure used to reduce epileptic seizures in extreme cases in which patients are unresponsive to epileptic medication. It occurs most commonly in children and is successful in 85% to 90% of cases. Most remarkably, many patients who experience hemispherectomy go on to become high-functioning adults.

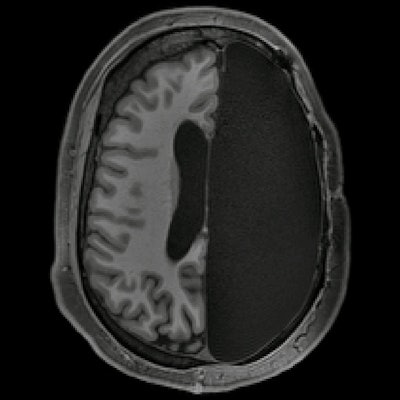

In the current study, researchers sought to explore the phenomenon by using fMRI to examine the brains of six adults who as children underwent brain hemispherectomies between the ages of 3 months and 11 years to reduce epileptic seizures. The procedure left them with a considerable portion of their brain removed.

The obvious question is: What was the underlying process behind how their brains compensated for the loss?

"Does the compensated level of cognition that can occasionally be found in such patients depend on a different or reorganized set of functional networks or does mostly intact cognition always go hand in hand with the basic set of resting-state networks?" the researchers asked.

To answer that question, Kliemann and colleagues performed resting-state functional MRI (fMRI) scans on six adults in their 20s and 30s who had undergone brain hemispherectomies between the ages of 3 months and 11 years to reduce epileptic seizures. For comparison purposes, six demographically matched healthy control subjects also received fMRI scans.

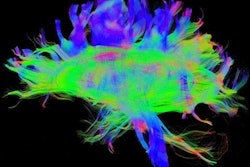

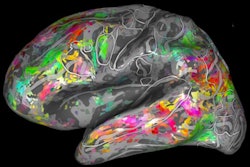

During the exams, the participants were asked to stay awake while the researchers charted network brain activity between regions associated with vision, movement, emotion, and cognition. The researchers then used a previously validated cortical parcellation approach to segment the brain into seven networks and more comprehensively determine how well they functioned across each region and across the cerebral cortex.

Interestingly, two hemispherectomy subjects showed abnormally high connectivity for all seven networks, above the normal ranges of the control subjects, while three patients achieved connectivity in the 90th percentile, above the normal range for at least four of the seven networks, compared with the healthy controls. The network connections in the hemispherectomy patients were particularly strengthened in the postcentral gyrus, which deals sensations such as warmth or pain; the precentral gyrus, which is associated with motor skills; and the visual networks.

Structural MR image shows slices from the top to the bottom of the brain of an adult who had one complete hemisphere resected in childhood due to epilepsy. Global interhemispheric connectivity remains intact, yet with increased connectivity between networks, supporting cognition despite atypical brain anatomy. Images courtesy of Caltech Brain Imaging Center and Cell Reports.

"Our findings raise intriguing new questions about the neural basis of integrated cognition and conscious experience," the authors wrote. "In our hemispherectomy patients (with full anatomical resection), there is simply no contralateral hemisphere present at all, eliminating bilateral resting-state networks and the possibility of bilateral contributions to conscious experience. Thus, our findings argue that the evidently intact conscious experience of our hemispherectomy patients may be related both to their intact resting-state networks and to the increased between-network interaction that we found."