Radiation therapy patients report less anxiety when a medical physicist explains technical aspects of care and how it is delivered, according to research presented at the American Society for Radiation Oncology (ASTRO) annual meeting in San Antonio.

Todd Atwood, PhD.

Todd Atwood, PhD.Lead author Todd Atwood, PhD, said the results showed that medical physicists could add value to patient care in a patient-facing role in addition to their regular work "behind the scenes" to ensure safe and effective care.

"It illustrates how care teams can partner more effectively with patients as they make their treatment decisions and navigate the radiation therapy process," said Atwood, an associate professor and senior associate division director of transformational clinical physics at the University of California, San Diego, in a statement from ASTRO.

Prior studies have shown that patient-related stress can negatively impact outcomes after radiation therapy. Patients may search online to know more about their treatment but find information that is nonspecific or too complex, adding to stress and anxiety, notes Atwood.

Medical physicists work with radiation oncologists to ensure safe patient treatment plans, including performing safety tests on equipment. But could they also supplement patient education and potentially improve patient outcomes by reducing patients' treatment-related stress?

In the trial, 66 patients with different types of primary cancer were randomly assigned to the Physics Direct Patient Care (PDPC) arm or the control arm which was standard of care.

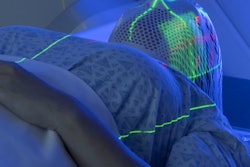

The PDPC group received two consultations prior to treatment with a medical physicist who explained the technical aspects of their care -- how treatment is planned and delivered, how the technology works, and what helps to keep them safe.

Before interacting with patients, the five medical physicists in the study completed a patient communication training program that included radiation oncology-specific lectures, simulated patient interactions, and supervised consults.

Patients completed questionnaires at four time points (after enrollment, after the simulation, after the first treatment, and after the last treatment) to assess anxiety, technical satisfaction, and overall satisfaction.

The decrease in anxiety for the PDPC arm, compared with the control arm, was statistically

significant at the first treatment (p = 0.027) time point.

The increase in technical satisfaction for the PDPC arm, compared with the control arm, was statistically significant at the simulation (p = 0.005), first treatment (p < 0.001), and last treatment (p = 0.002) time points. What's more, the increase in overall satisfaction for the PDPC arm, compared with the control arm, was statistically significant at the first treatment (p =0.014) and last treatment (p = 0.001) time points.

Although the consults were beneficial for patients generally, Dr. Atwood said that they may be particularly useful to patients who are more prone to anxiety. Among those receiving the additional consults, over the course of treatment, the percentage of patients reporting high anxiety levels dropped by more than half, from 31.3% to 12.5%.

Dr. Atwood said, "We've thought medical physics consults had great potential for years, but now we have a clearer understanding of how they positively impact the patient experience."