Can ultrasound reliably assess blunt abdominal trauma injury? No. Is it a good triage tool in the ER? Maybe. Is it fast, cheap, radiation free? Sure. How well does it diagnose seatbelt-related injuries? Not very. But the use of new contrast agents and advanced techniques might improve the picture.

A pair of studies presented at the 2001 RSNA meeting in Chicago measured ultrasound's ability to evaluate suspected blunt abdominal trauma in adults and children, respectively. In both groups, ultrasound came up wanting.

Corresponding to previous research, the studies found that ultrasound has moderate-to-high sensitivity and near-perfect specificity for the detection of free intraperitoneal fluid. But while free fluid is one predictor of injury, it isn't present in perhaps a quarter of the cases. Another question -- how well does ultrasound detect direct parenchymal organ injuries? -- had not been well studied.

The researchers found that ultrasound's ability to detect parenchymal organ injury per se is hit-and-miss, with low sensitivity that varies somewhat depending on which organ is injured. Thus, while sonography retains an important role in trauma imaging, the studies raised important questions as to how, when, and even whether the modality should be used alone.

The Swiss study

In the first study, Swiss researchers evaluated 206 consecutive patients with anamnestical or clinical suspicion of blunt trauma injury, using both ultrasound and CT. After excluding some patients who were not in pain, and had normal lab results and normal initial ultrasound, 144 patients completed the evaluation.

"The goal of our study was to determine the value of sonography in the assessment of peritoneal fluid and the detection of organ injuries of patients in our center," said Dr. Pierre-Alexandre Poletti from the Hôpital Cantonal, University of Geneva.

In the study by Poletti and colleagues Dr. Karen Kinkel and Dr. François Terrier, all patients underwent ultrasound followed immediately by CT. The researchers used a PQ 5000 (Marconi Medical Systems) or CT/i scanner (GE Medical Systems, Waukesha, WI) with 5-mm-thick contiguous slices, a table speed of 5 mm/sec, and a pitch of 1. Most patients received 140 ml of iodinated contrast intravenously, and some received 300 ml of oral contrast.

Ultrasound examinations were performed using an SSD 2000 Multiview scanner (Aloka, Wallingford, CT). A lack of abnormal findings on either modality was considered a true negative result, while abnormal findings on both CT and ultrasound were deemed a true positive. For the first ultrasound, the radiologists were unaware of CT results.

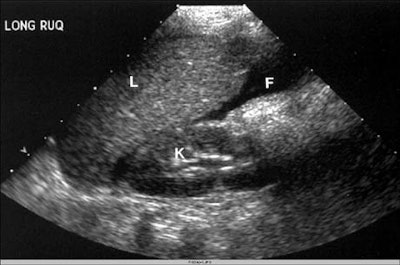

"We assessed the presence of peritoneal and retroperitoneal fluids" (in the Morrison's pouch, perisplenic region, the paracolic gutters, Douglas’ pouch, and the peritoneum), "and looked for injuries of the liver, the spleen, pancreas and bowels," Poletti said. "CT results were compared with ultrasound findings."

If the first ultrasound was falsely negative, an attending radiologist performed a second scan of the false-negative area, usually with Doppler. For the second ultrasound exam, the radiologists were aware of the CT results, Poletti said.

|

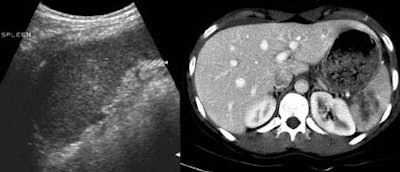

According to the results, CT identified free fluid or organ injury in 112 of 206 patients (54%). The most frequently injured organs were the spleen (39%), liver (30%), kidney (8%), mesenteric bowel (8%), bladder (4%), and the pancreas (3%).

For the depiction of free peritoneal fluid, ultrasound was 92% sensitive at the first pass, and 98% sensitive by the second exam. For overall detection of abdominal injury by either free fluid or organ parenchymal injury, ultrasound was 72% sensitive and 91% specific on the first pass. By the second exam, ultrasound was 91% sensitive and 100% specific.

However, for visceral injury without free fluid, ultrasound was only 41% sensitive and 92% specific on the first pass. By the second exam, sensitivity had risen to 51% and specificity to 100%. A quarter of the organ injuries seen on CT did not have free fluid; therefore the first ultrasound missed 73% of these parenchymal injuries, Poletti said.

|

"Ultrasound was very sensitive and specific [for detecting] free fluid when compared with CT results. However, it was very poor for showing parenchymal injuries... Twenty-five percent of the patients had visceral injuries with no associated free fluid," Poletti said. "Therefore, ultrasound is limited by the high amount of organ injuries that are not associated with free fluid."

The California study

Next, session moderator Dr. John McGahan from the University of California Davis Medical Center in Sacramento presented a study that sought to assess ultrasound's ability to detect organ injuries in pediatric blunt trauma patients.

The study, led by McGahan's UC Davis colleague Dr. John Richards, evaluated 744 pediatric patients (ages 2 weeks to 16 years, average age: 10) who underwent emergency ultrasound for suspected abdominal trauma. It compared the results of ultrasound to CT, and/or physical exam, lab results, and intraoperative findings.

"Emergency ultrasound has been shown to have very good sensitivity in adults, [from] about 63% to as high as 100% in the detection of free fluid or peritoneal blood," McGahan said. "Less is known about the accuracy in the detection of free fluid and hemoperitoneum in children, and very little is known about the detection of actual organ injuries."

The study sought to assess ultrasound's accuracy for the detection of free fluid and organ injuries. All of the ultrasound examinations were performed by sonographers.

"We looked for free fluid first, and if we saw that, we looked at the parenchyma of organs. If we didn't see free fluid and if we had time, we also looked at the parenchymal organs," McGahan said. The ultrasound was then followed up with either CT or laparotomy, he said.

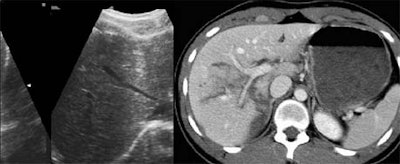

In all, 75 patients (10%) had intra-abdominal injuries. Ultrasound detected free fluid in 42 patients (56%).

For the detection of free fluid with ultrasound, "our sensitivity was actually fairly low," McGahan said. "We had 43 true positives, 36 false negatives, overall sensitivity of 56%. No matter what standard you look at, specificity was high," in the range of 98%.

|

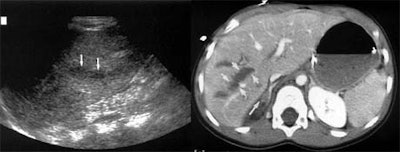

Ultrasound detected organ injuries in 9 patients (12%) in which no free fluid was identified. These included 3 splenic injuries, 3 liver injuries, and 3 renal injuries, for an approximate sensitivity of 70%, McGahan said. The inclusion of sonographic identification of parenchymal organ injury increased the sensitivity of ultrasound to 86%, with overall accuracy of 96%.

|

|

"In conclusion, emergency ultrasound is highly accurate and specific, but has moderate sensitivity for the detection of free fluid in pediatric abdominal blunt trauma patients. Some of our identification of actual organ injury was in the form of parenchymal abnormalities -- when you do identify [them], it does improve the sensitivity of ultrasound," he said.

The critics

The audience offered free peer-review services following the presentations.

"The determination of [ultrasound's] sensitivity all depends on the gold standard," said one attendee. "We do a lot of trauma studies at our institution, and we found out that almost all of our false negatives actually occurred in patients who had persistent abdominal pain. So in other words, [Poletti] selected the subset of patients that have persistent abdominal pain and then go on to CT -- and it turns out that's the subset where almost all of [ultrasound's] false negatives occur."

Moreover, patients who were excluded from the Swiss study due to a lack of abdominal pain may have had injuries that could not have been seen on CT, he said.

Said another: "The question in 2001 is: Is there a patient who comes to the trauma center who will not get a CT no matter what the ultrasound says? Unless of course they're thrashing, in which case they go directly from ultrasound to the operating room."

"We have a database of over 4,000 patients," another attendee responded. "If the negative ultrasound [patients] are stable for a period of 24 hours, they don't get any other tests, and that's 94% of the patients who come in for our trauma team. So that's 94% of patients [for whom] we don't do CT."

"We excluded patients who were unstable," Poletti said, "but that's not the patients we were concerned with because we know they have something wrong with them. The most difficult cases are the patients that have mild pain or trauma, and we don't know if we can discharge these patients or just observe them."

Finally, an audience member noted that in both studies, ultrasound seemed to have low sensitivity for small bowel lacerations, in line with the 44% sensitivity doctors at her institution had found. That means ultrasound does a poor job in assessing the growing number of childhood injuries related to seatbelt use, she said.

"I don't think ultrasound is the gold standard," McGahan responded. "I think it's a triage -- when you identify somebody who needs to go to the OR, you can see them right away and ship them up to the OR. But bowel and mesoenteric injuries, pancreatic injuries, other things are very tough to look at. You know there are other injuries we can diagnose such as congenital pneumothoraces, where [ultrasound] has a high sensitivity. [But] there are a number of limitations in ultrasound."

By Eric BarnesAuntMinnie.com staff writer

December 14, 2001

Related Reading

Intestinal ultrasound can differentiate organic from functional bowel disease, September 17, 2001

US, CT replace surgery for some abdominal stab wounds, August 29, 2001

Ultrasound offers fast, reliable screening for blunt abdominal trauma, February 28, 2001

Copyright © 2001 AuntMinnie.com