This is the first installment of a two-part white paper contributed by Dr. Stefano Ciatti and his colleagues at the Studio Ecograficao Dott. Stefano Ciatti in Prato, Italy. It explores the role of 3-D ultrasound in shaping the perceptions of pregnant women toward the developing fetus.

"A vase, the earth, the female body are all considered capable of hiding, containing, producing, and providing substances that permit the continuation of the human existence" (Page Du Bois, Il Corpo come Metafora, Laterza, Roma, 1990).

Summary

Ultrasound screening in antenatal surveillance of the fetus is part of our healthcare service's routine protocol. These examinations, performed at regular intervals, control the physical aspect of the pregnancy, but do not provide for the psychological needs of the mother-to-be.

Modern society tends to present the ideal woman as dynamic and independent, without considering her needs, especially during the precious period of pregnancy. Many women are not satisfied or reassured by the lack of sensitivity and lack of explanation when undergoing an obstetrical ultrasound examination. The women in our series sought to have a repeat ultrasound examination, not always aware of the possibility of 3-D ultrasound scanning, in an attempt to find greater satisfaction and peace of mind with respect to their pregnancy and the new life that they were creating.

The last few years have seen the introduction of 3-D ultrasound in the clinical practice of obstetrics. This technique overcomes several limitations of conventional ultrasound, allowing a more detailed assessment of morphological features of the fetus, without any restriction on the number or orientation of the scanning planes. Three-dimensional ultrasound allows the anatomy of the fetus to be presented to the mother-to-be in an understandable manner, or in other words, in photographic style via 3-D reconstruction (surface rendering).

These easily understood images not only permit the reality of the pregnancy and the individuality of the fetus to be faced by both parents, but also provide greater reassurance with respect to traditional ultrasound. The development of 3-D ultrasound presents us with the opportunity to provide an examination that produces reassurance and serenity, and at the same time demonstrates the anatomy of the fetus both to the doctor and mother-to-be in a clear and precise manner.

In this study we examined the psychological impact of 3-D ultrasound on the mother-to-be and on the parents-to-be. We sought to understand its meaning in the context of pregnancy, and how the parents-to-be feel when presented with pictures of their baby before it has been born. We also sought to determine the role that these images can have on the parents-to-be in satisfying their psychological needs in a modern world where medicine does not take into consideration the feelings and psychological needs of pregnant women and expecting parents.

Introduction

We are all aware of the huge quantity of stone, bone, and terracotta statues found by archeological excavations of prehistoric sites that portray plump female figures with babies: these obviously are depicting the mother/child diade archetipica. Historically the Madonna with child (mother of excellence in Western culture) has been the inspiration of more than 2,000 years of sacred art.

|

| Figure 1, Madonna with child. |

The success of these representations underlines the importance that, from the beginning of time, was attributed to the biological and creative qualities of the female body. These qualities were expressed in famous and sacred images when pregnancy and birth were not connected with sexuality and with the masculine intervention, but were attributed to imprecise nutritive female qualities that man does not possess. Femininity has always been celebrated as the giver of life. Certainly those ancient statues represented the unmistakable female qualities needed for procreation from one generation to the next.

|

| Figure 2, Madonna Del Parto by Piero della Francesca, circa 1460. |

The sanctity with which one regarded the creation of a new human being resulted originally in the involvement of the entire community (village), and then the entire family. The older and wiser women (mother, grandmother, aunts) gave advice from their experience. They used proverbs that were suitable for the various stages of the pregnancy and related to beliefs that, although without medical backup, were diffusely accepted. These customs or passage rituals were recognized as the key to curing and alleviating symptoms and were given value by those who had previously suffered similar complaints and who were witnesses to their value (Neumann, E., Storia delle Origini della Coscienza, Astrolabio, Roma, 1978).

The continuing evolution of scientific and medical research, with its various technological applications, has made and continues to make improvements in the quality of human life. Consequently, certain moments in life that once had a private and intimate dimension, and were accompanied by so-called passage rituals that gave significance to the event of birth, today are more commonly entrusted to medical science.

As Luigi Zoja observed, "Up until not so many years ago, birth and death, normally, had a common place in the home and were administered to by the family hierarchy. Today both of these events have been transferred to hospitals, under the supervision of an effectively and psychologically foreign or unrelated hierarchy of technicians" (Zoja, L. Crescita e Colba, Anabasi, Milan, 1993).

With the aim of prevention, those moments of "crises" related to a natural and physiological transformation and not a real pathology (it is not the case to speak of pregnancy in terms of a "normal disease") are entrusted almost exclusively to medical science.

"In some ways, as has been observed, one tends to simplify ‘the bad object’ insofar as the pregnancy fills not only the woman and her uterus, but also her needs. Just think of the so-called ‘wants’ that tradition attributes to this new physiological state and activates a sort of protection against dissatisfaction and frustration. The pregnancy can restore an illusion of completeness; the capacity of the woman to become pregnant can be privately lived as proof of her omnipotence…. The baby that she carries or that she can carry ‘is’ the proof of her omnipotence: the baby, apart from its genus, introduces the completeness!" (Birreaux, A., L’adolescente e il suo corpo, Borla, Roma, 1993).

From the beginning, the pregnancy immediately becomes a medical event and a set of clinical controls, carried out at various levels and at specific intervals with highly sophisticated instrumentation. In many ways these tests and controls have become the new rituals or customs to which is entrusted that important passage of gestation and the birth of a new human life. The aim of all this is to avoid or limit as much as is possible any suffering, both to the mother-to-be and her baby.

It is not surprising that this medical way of controlling pregnancies, due to its scientific complexity, has not succeeded in integrating itself fully with traditional rituals and customs. Medicine has replaced the customs that effectively sustained and supported the mother-to-be during the period of the pregnancy with the aim of preventing her feeling alone to face the unknown.

As a result, medicine has caused a process of repression to the traditions and customs surrounding pregnancy, and, more importantly, to the psychological and social needs of women during this time of change that were once fulfilled. In spite of these many changes and even though one lives a life that is ever more rationally programmed, those needs of the female soul, particularly during the special moment that we are dealing with in this study, have not diminished.

In the present study we address precisely this moment of the creation of another human being from the existing generation with the help of several instruments of observation. The continuing evolution of scientific and medical research, with its technological applications, has expanded dramatically and tends to yield a better quality to human life.

We concentrated in particular on the ways in which state-of-the-art technology and the images it is capable of producing for diagnostic purposes can influence, condition, and stimulate pregnant women evoking and reaching to the depths of the subconsciousness. During our research we considered it important to take into account the fears of the subconscious.

These threatening subconscious representations are linked with the idea of change and without the concrete reality are effectively dangerous or worrying. This study is concentrated on the moment in which the pregnant woman begins her journey of clinical prevention and by undergoing the various examinations comes face-to-face with the obstetrical ultrasound examination -- nowadays accepted as part of the routine procedure.

We concentrated our objective on the reactions provoked by the photographic-style 3-D images that are readily understandable to the layman, unlike those of traditional ultrasound. The aim of this study was to determine the exact significance that these images can have for the pregnant woman and for the couple. We wanted to understand the impact of seeing the product of conception in such a direct manner and in its complete form; in other words, to discover and to reveal to the parents-to-be something that for centuries was considered to be part of the mystery of the "closed gestational sac."

"A mystery certainly linked with the taboo of sexuality, always accompanied with prohibition that results in inhibition (that, despite the contrary appearance, is an essential element in the conservation of desire) embarrassment, modesty, inasmuch as they belong to the institutional world and characteristic of and in keeping with the transformation, and cannot be readily controlled," Don Francesco, F., Nello Specchio di Psiche, Moretti & VitaliBergamo, 1996).

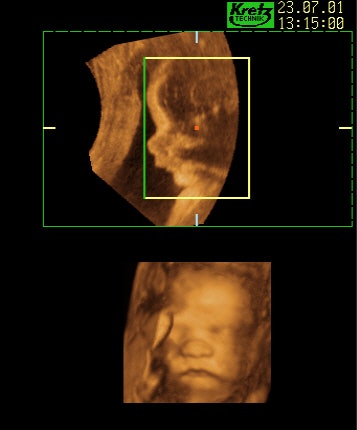

Traditional obstetrical ultrasound, for those not in this field of work, does not reveal a complete picture of the future baby. This is because it is capable only of revealing a section or slice of an organ or limb and without an explanation from the doctor or sonographer, the parents-to-be cannot determine the significance of the images on their own.

|

| Figure 3, a comparison between a 2-D and 3-D representation of a baby’s face. Image courtesy of Dr. Stefano Ciatti. Upper image: A traditional 2-D ultrasound line profile of the baby’s face (perhaps the most easily recognized line representation of the baby that the parents-to-be can understand). Lower image: A photographic-style representation of the same baby’s face by 3-D ultrasound that parents-to-be can readily understand and appreciate. |

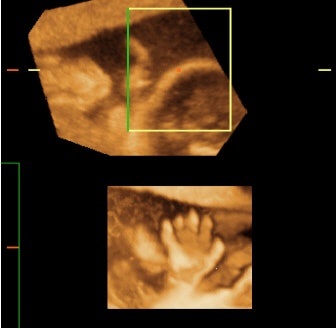

Women in our study underwent grayscale traditional ultrasound imaging followed by color 3-D ultrasound imaging. Two-dimensional traditional ultrasound pictures demonstrate line representations of the developing baby (for example, the outline profile of the baby’s face), whereas 3-D ultrasound images produce a more realistic representation of the fetus (for example, a photographic-style image of the whole face including eyes, lips, nose, cheeks, etc.).

|

| Figure 4, a comparison between 2-D and 3-D representations of a fetal hand. Upper image: A traditional 2-D ultrasound image of a fetal hand, which, without an explanation is difficult for the parents-to-be to comprehend. Lower image: A 3-D ultrasound photographic- style image of the same fetal hand, which is much more easily recognized and appreciated by the parents-to-be. Images courtesy of Dr. Stefano Ciatti. |

The clarity of these 3-D pictures dramatically demonstrate the concrete reality of the pregnancy and the developing baby to the parents-to-be. The fact that these pictures are 3-D representations of the fetus, and therefore similar to all of our 3-D representations in life, allows almost anyone to appreciate and understand what they are looking at very quickly, unlike traditional ultrasound pictures.

As a result, the reality of the pregnancy is offered via a television screen. Remember that in today’s world, one often considers credible and real that which one sees, in particular, on the television. It has been noted that for many, only that which is shown on television is real, while that which is not confirmed by means of television is considered with doubt, or even as nonexistent.

|

| Figure 5, an example of a televised snapshot of the fetus at 28 weeks gestation. Image courtesy of Dr. Stefano Ciatti. |

It is from this perspective that we looked at this study of 51 pregnant women who underwent fetal ultrasound, the majority of cases following medical protocol, not always aware of the difference between traditional and 3-D ultrasound.

Materials and methods

The study was conducted at the private ultrasound practice of Dr. Stefano Ciatti, in Via San Giorgio, Italy, on a consecutive series of 51 pregnant women who attended the institute for an obstetrical ultrasound examination. These examinations were conducted during a period of approximately three months on consecutive pregnant patients. All of the women participated in the research on the basis of choice. Only two withdrew from the research for reasons of a practical nature.

The women in our study agreed to fill in an auto-evaluative questionnaire Emas.S (Endler, Edwards, Vitelli) which measures anxiety levels and is composed of 20 questions: 10 of these measure the emotional component and 10 measure the cognitive preoccupation of the patient. After completing the questionnaire and the examination, the women underwent a psycho-dynamic interview, which took place before receiving the written report of the obstetrical examination. In the majority of cases the women were accompanied by their respective partner, who also played an active role in the interview.

The interviews were in part directed in order to gather relevant data as to the objective characteristics of the pregnant women. This interview allowed them to freely express themselves from the viewpoint of their own personal story within the original family, the story of the couple, and the sense given to their pregnancy. In particular, attention was paid to the expressed gestures of the women, through which conflicting and anxious sentiments in relation to the pregnancy as well as in relation to the event of the 3-D exam and the way in which it reveals the state of health of the fetus could be expressed and studied.

|

| Figure 6, an example of a televised snapshot of the fetus at 34 weeks gestation. Image courtesy of Dr. Stefano Ciatti. |

Objective characteristics of the women as revealed by the questionnaire were as follows:

Place of origin.

- 35 of the women lived in Prato City.

- 16 of the women came from outside of Prato (Greve in Chianti, Signa, Montemurlo, Florence, Montelupo, Vaiano, Carmignano, 2 from Campi Bisenzio, 4 from Empoli, 3 from Pistoia).

Age of the women.

- 13 were between 24 and 29 years of age.

- 38 were between 30 and 39 years of age.

Level of education.

- 18 had attended the obligatory school program.

- 24 had achieved the level of high school diploma.

- 9 had a university degree.

Working conditions.

- 14 perform an autonomous job (free professional, shopkeeper, craftswoman, entrepreneur).

- 19 are employees or teachers.

- 9 are other workers.

- 7 are homemakers.

- 2 are students.

Gynecological status.

- 33 are undergoing their first pregnancy.

- 16 are undergoing their second pregnancy.

- 1 is undergoing a third pregnancy.

Preceding ultrasound examinations.

- 4 women underwent an obstetrical ultrasound examination for the first time.

- 47 of the women in the study came to the clinic after having had an obstetrical ultrasound examination in another institute including: during a regular visit to the gynecologist, at the time of amniocentesis, or in the hospital.

- 38 women had a 3-D obstetrical ultrasound examination for the first time.

- 5 women had a 3-D obstetrical ultrasound examination for the second time.

- 7 women had a 3-D obstetrical ultrasound examination for the third time.

- 1 woman had a 3-D obstetrical ultrasound examination for the fourth time.

By Dr. Stefano Ciatti, et al

AuntMinnie.com contributing writers

December 29, 2003

Part II of this white paper will appear on Tuesday, December 30.

Related Reading

3-D ultrasound shows promise in neonatal, pediatric neurosonography, November 4, 2003

Turf Wars in Radiology IV: Radiologists, ob/gyns sound off on fetal imaging, September 26, 2002

Genetic ultrasound capable of preventing amniocentesis losses, July 8, 2002

Multinational study makes case for first-trimester sonography, June 12, 2001

MRI second-guesses fetal ultrasound, April 25, 2001

Copyright © 2003 Dr. Stefano Ciatti et al