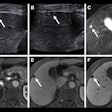

CHICAGO - An audible crack is accompanied by a distinct flash of brightness -- or so it goes when a person cracks his or her knuckles while being scanned via ultrasound, according to researchers from California. They shared their conclusions about the common sound at this week's RSNA meeting.

The flash of light that fills the space between the bones of the finger is consistent with a gaseous substance, said Dr. Robert Boutin, a professor of radiology at the University of California, Davis Health System. He said the "pop" is due to cavitation in the joint.

In trying to solve the mystery of what exactly is behind the cracking sound, Boutin (a self-confessed noncracker) and colleagues enrolled 40 individuals in their study: 30 who claimed they habitually cracked their knuckles and 10 who said they were noncrackers. The study was filled on a first-come-first-served basis; Boutin said he believed the crackers rallied to the trial because they were more interested in finding out about what was happening inside their fingers than the noncrackers.

There have been several theories over the years as to what happens when knuckles crack, and the debate still rages over how it happens and if it is harmful, Boutin said. The researchers obtained video ultrasound images of 400 metacarpophalangeal joints, as participants tried to crack their knuckles, and they also recorded static images of the joints before and after the cracking attempts.

Two radiologists each read all of the scans, looking for features that correlated with the cracks, and orthopedists also examined the patients to evaluate grip strength, range of motion, and the looseness of each metacarpophalangeal joint.

"What we saw was a bright flash on ultrasound, like a firework exploding in the joint," Boutin said in an RSNA press release. "It was quite an unexpected finding."

"We're confident that the cracking sound and bright flash on ultrasound are related to the dynamic changes in pressure associated with a gas bubble in the joint," he added, though more research is needed to determine whether the sound or flash comes first.

Overall, there was no difference in grip strength or joint looseness between the groups. But those who cracked their knuckles did seem to have greater range of motion. No pain or swelling was associated with knuckle cracking.

"There's no evidence to indicate that it's bad for you in the short-term, and there's no evidence that it's irritating to the joint," Boutin said. "Although there may be irritation to the coworker or family member next to you."

He added that it's still unclear what happens over time, as some studies have shown that swelling and a decline in grip strength did eventually occur, even though patients didn't develop osteoarthritis -- "so I think the jury is still out," he said.

In commenting on the study, press conference moderator Dr. David Hovsepian, a professor of radiology at Stanford University, said, "It's just a snapshot in time, so you'd love to get this group back in 10 years and see, if they continue to crack their knuckles, how does their range of motion change, and are there any secondary effects."

"Intuitively you'd think it has an effect over time, but maybe not," said Hovsepian, a noncracker. "We've seen orthopedic studies of runners where the cartilage is healthy even though these patients have been running for more than 20 years. You'd think that would pound the cartilage into oblivion, but maybe it keeps the cartilage resilient."