A Spanish team used ultrasound scans to document lung abnormalities in three patients who recovered from COVID-19 but still had persistent symptoms months later. The November 7 study adds to a growing body of research on patients with lingering COVID-19 symptoms, often described as long-haulers.

The three patients in the study, which was published in the Journal of Ultrasound in Medicine, had mild cases of COVID-19 but lingering shortness of breath. Ultrasound scans revealed a variety of pulmonary findings, including irregular pleural lines and B-lines, which correlated with abnormalities on CT scans.

"This would explain some of the residual symptoms that many patients describe after several weeks from medical discharge, even in mild patients," wrote the authors, led by Dr. Yale Tung-Chen, PhD, an emergency physician at La Paz University Hospital in Madrid.

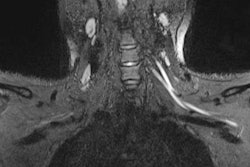

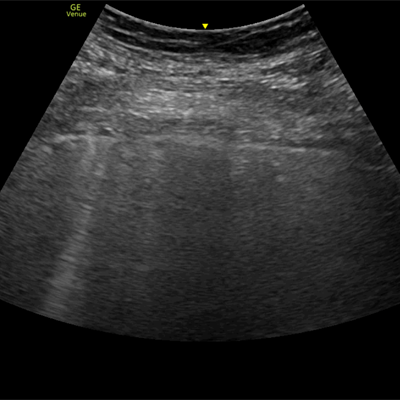

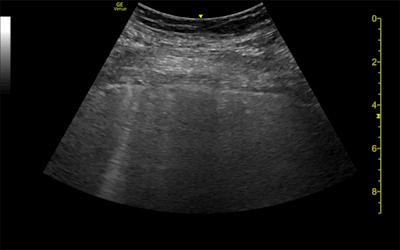

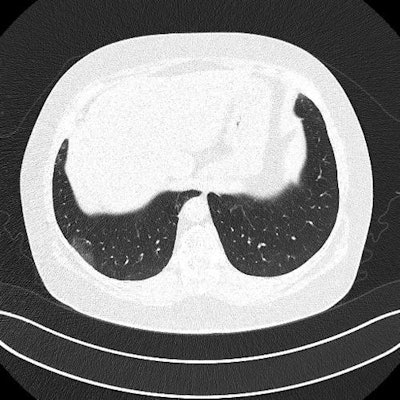

Ultrasound and CT images from a 62-year-old woman with long-term COVID-19 symptoms. The patient, who was not part of the study, visited the Madrid emergency department with persistent dyspnea and cough. The ultrasound image (above) shows an irregular pleural line and some B-lines, which correlate to ground-glass opacities in the lower lobes on CT (below). Images courtesy of Dr. Yale Tung-Chen, PhD.

Ultrasound and CT images from a 62-year-old woman with long-term COVID-19 symptoms. The patient, who was not part of the study, visited the Madrid emergency department with persistent dyspnea and cough. The ultrasound image (above) shows an irregular pleural line and some B-lines, which correlate to ground-glass opacities in the lower lobes on CT (below). Images courtesy of Dr. Yale Tung-Chen, PhD.

The study included a 35-year-old woman, a 41-year-old woman, and a 64-year-old man who visited the hospital emergency department with complaints of muscle weakness and dyspnea on exertion. The patients had all tested positive for COVID-19 more than eight weeks prior, and their laboratory and physical exam results were normal.

The patients underwent both lung ultrasound and chest CT scans, which revealed a variety of abnormalities related to COVID-19:

- The 35-year-old woman had a mild, irregular pleural line and B-lines in her right anterior chest on ultrasound, which correlated with ground-glass opacities on CT.

- The 41-year-old woman had an irregular pleural line in her right lateral area on ultrasound, which correlated with pleural thickening on CT.

- The 64-year-old man had a marked, irregular pleural line and multiple B-lines on ultrasound, which correlated with fibrotic changes on CT.

Emergency physicians at the hospital discharged all three patients, referring them to a pulmonary outpatient clinic. The cases reflect a larger pattern of long-term imaging irregularities in some patients who have recovered from COVID-19. At the moment, there are more questions than answers.

"Long-term follow-up is required to determine whether this represents irreversible fibrosis, although the prognostic implication of this finding is controversial: some suggest it is a sign of stabilization, whereas others suggest that it could indicate a poor outcome," the authors wrote.

The cases also beg the question of the best imaging modality for long-term follow-up of patients with persistent COVID-19 symptoms. While chest radiography and CT scans are being used as first-line modalities for symptomatic patients, the authors questioned their appropriateness for patients who may need long-term repeat imaging.

Ultrasound could be one alternative for these patients because the modality is both affordable and radiation-free. The authors also pointed to ultrasound's widespread availability, quick exam time, and ease of use in both medical and nonmedical settings.

However, ultrasound has its own drawbacks, notably limited sensitivity. This was especially evident in the case of the 35-year-old woman whose mild irregular pleural line on ultrasound corresponded not to abnormal pleura on CT but parenchymal tissue changes.

"The findings in this report raise the question of whether lung ultrasound can be used in the longer-term follow-up of patients with COVID-19, by means of assessing still-symptomatic patients, as a radiation-sparing, novel care path worth exploring," the authors concluded.