Virtual reality training systems, whether they use gaming elements or not, enhance learning for trainees using focused lung ultrasound, research published December 17 in Ultrasound in Medicine and Biology found.

A team led by Jonas Larsen from the University of Southern Denmark found that novice trainees in gamified and nongamified immersive virtual reality training groups performed focused lung ultrasound on the same level as doctors with intermediate clinical ultrasound experience.

"Immersive virtual reality training could be used for unsupervised out-of-hospital training to elevate the competence level for new trainees," Larsen and colleagues wrote.

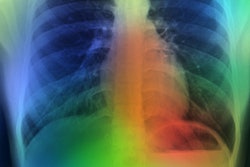

Previous studies have shown that focused lung ultrasound is accurate for common conditions seen in emergency settings and offers the benefit of versatility. The competency of ultrasound users is important in such settings for the sake of diagnostic success and patient safety, but gaining competency in clinical environments can be challenging, the team noted.

Virtual reality doesn't have to be all Star Wars and shoot-'em-up style gaming. Health companies have collaborated with game developers in recent years to help improve training among staff members and residents, including radiologists.

Larsen and colleagues explored the educational impact of virtual reality learning in both gamified and nongamified training modules (VitaSim) on novice trainees using focused lung ultrasound. The team also wanted to compare each type of module's performance with test scores from novices, intermediates, and experienced ultrasound users in a study that included 48 participants (24 with gamified and 24 with nongamified immersive virtual reality training).

The gamified group of participants completed quizzes and training missions in virtual medical rooms to earn experience points to unlock more rooms. The nongamified group had participants choose their own path throughout training, allowing for skipping certain training rooms if the participant deemed it unneeded. The researchers calculated test scores by adding up points given for correct assessment of final diagnosis from each case, which relied on sonographic findings and evaluation of patient history and clinical findings.

The investigators found no significant difference between gamified and nongamified groups when considering average test scores (15.5 points vs. 15.2 points, p = 0.66) -- which suggests that gamification elements do not affect learning outcomes. They also found that average scores in both groups were not significantly different from those of known intermediate-focused lung ultrasound users.

While the study results are promising, the authors noted that such simulated training in ultrasound is not meant to substitute for clinical practice. They suggested that training on simulated patients could be a pre-clinical tool, allowing trainees to safely practice their competency skills before supervised training.

"This could potentially reduce the workload of ultrasound experts by decreasing the need for training-related confrontations with trainees regarding basic sonographic challenges, thus allowing the expert supervision to be reserved for more complex challenges in a clinical setting," they concluded.