Catey Terry embarked on her fabulous 40s last year. Along with the birthday celebrations, the Columbia, MO, resident underwent her first mammogram. She shared her experience with AuntMinnie.com.

"The mammographer was with me from start to finish, totally professional, although she did ask if it was my first time," Terry said. "When I said 'yes,' she said not to worry ... just the ever-popular 'You’ll feel some pressure.' The plates were cold and it did feel really uncomfortable, especially the compression part, but my memory is more sort of being on my tiptoes, hence off-balance. However, being squished to death really did hurt."

"I'd heard myriad tales of who it hurts more, the women with no breasts or the 44 DDs," she continued. "I also remember the time frame of the actual compression being about as long as one could stand. Tears did well up in the corners of my eyes, but no actual crying. (I had a) general sense that this technology felt really old-fashioned. Like squishing your breasts from top to bottom and side to side really detects cancerous masses -- wow."

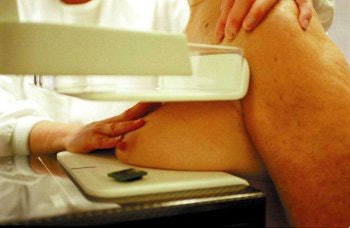

For that matter, many average, eligible women can probably whip up a list of reasons why they hate breast cancer screening: taking the time to go to the breast center is a hassle, it's anxiety-inducing, the bucky is chilly, a virtual stranger is handling her in an intimate way, etc.

A major reason women dodge mammography is the discomfort -- some would call it flat-out pain -- during breast compression. The importance of compression is not lost on breast imaging professionals: "squishing the breasts" allows for a reduction in breast thickness, as well as in radiation. The compression results in better image quality and a more accurate read by the radiologist.

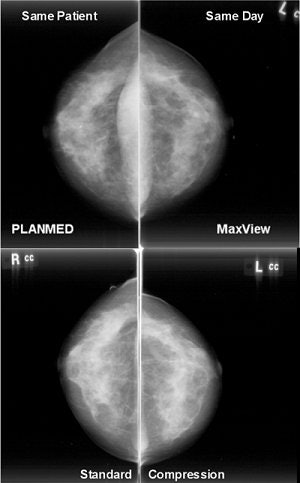

|

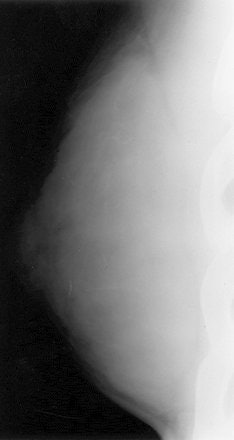

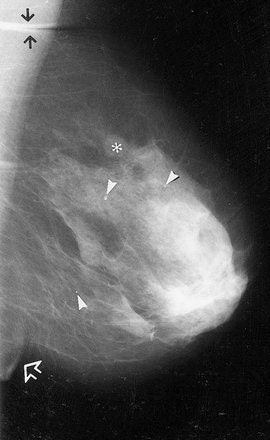

Standard negative mammograms: 1965-1975. Standard examination included a 90° lateral and craniocaudal (CC) view of each breast. Lateral (above) and CC (below) direct-exposure film mammograms. There was only slight (if any) compression of the breast during exposure, which impaired depiction of tissues close to the chest wall because the x-ray beam could not effectively penetrate these thicker regions of the breast without grossly overexposing the thinner regions close to the nipple. Sickles EA, "Breast Imaging: from 1965 to the present," Radiology 2000; 215:1-16.

|

While women may understand that explanation on an intellectual level, it may not translate on an emotional one. Of course, the irony is that women are willing and able to endure a lot more pain than that of a mammogram (childbirth, anyone?). When it comes to aesthetic gain, women flock toward cringe-inducing treatments -- bikini waxing, microdermabrasion, chemical facial peels, Botox injections, laser hair removal, breast lifts, and liposuction, to name a few.

So what is it about compression in particular that makes women so antsy? And what can mammographers do about it? AuntMinnie.com spoke with breast imaging experts on how to properly manage compression to enhance the breast-screening experience, ensure quality images, and make sure that women come back on a regular basis.

The fear factor

In study after study, women have expressed their concerns about pain during breast screening. In 1999, a survey in Social Science & Medicine reported 75% of the participants reported pain during mammography. A year later in a second study that also asked patients to assess discomfort levels on a pain scale, nearly 31% of the respondents reported severe to moderate pain (Social Science & Medicine, October 1999, Vol. 49:7, pp. 933-941; Breast Cancer Research and Treatment, April 2000, Vol. 60:3, pp. 235-240).

Based on more recent research at Wake Forest University in Winston-Salem, NC, women said that compression was partly to blame. Penny Sharp, Ed.D.; radiologist Dr. Rita Freimanis; and colleagues interviewed 200 women over the age of 40 immediately after screening mammography. Their goal was to understand the pain experience during the different procedure stages.

They found that while the overall pain ratings were low, more than 30% of the 200 women gave compression a pain score of five or higher (on a scale of 1 to 10), versus only 10% who complained about having their skin pulled (Archives of Internal Medicine, April 14, 2003, Vol. 163:7, pp. 833-860).

But perhaps a more interesting aspect of this study was that 39% reported that waiting for the results was the most stressful part of the procedure. In large part, this is where the anticompression sentiment emanates.

|

| Craniocaudal-view positioning prior to compression. Image courtesy of BioLucent. |

"Most of it is fear of the results," concurred Dr. Lauralyn Markle from the MemorialCare Breast Center at Saddleback in Laguna Hills, CA. "Once you talk to (women), that's what they are afraid of."

In fact, breast imaging has only one truly scary "C," and it isn't compression, according to Bonnie Rush, a mammography technologist and president of Breast Imaging Specialists in San Diego.

"When a woman comes in for a mammogram, the message that keeps going through her head is the mantra of breast cancer: 'I've probably got breast cancer,' 'I'm sure I've got breast cancer,' 'What if I've got breast cancer?''' Rush said. "Instead of talking about that big 'C,' she talks about ... compression since she dares not talk about her fear of breast cancer."

Screening advocates must bear some responsibility for this attitude because of their "scared-straight" approach in order to encourage compliance, Rush added.

Lisa Labbe, a mammographic RT and operations manager at Tucson Breast Center in Arizona, believes that breast health smarts are not the same as breast cancer stress.

"I do not put cancer pamphlets out in the waiting area," Labbe said. "We have an education room, and if a patient has concerns, we pull them aside and have the information in another place. You don't want to bring a patient into a (screening) center and have cancer everywhere."

In fact, playing into the cancer fear is a second issue that may make women inordinately averse to compression and breast screening as a whole.

"In the U.S., we have placed a great emphasis on the value of breasts. It's a huge psychosocial issue for women," Rush said.

A passing thought of breast cancer may send a woman into a panicked tailspin with regard to her femininity, attractiveness, social status, ability to maintain a relationship, and so on, Rush explained. In turn, the mammographic technologist may have to contend with someone who is nothing less than a ball of nerves -- and compression becomes the convenient scapegoat.

Taking the pressure off

So what are the options for helping patients deal with compression? The solutions lie in a technical and emotional approach to breast imaging.

The most radical theories put forth on paper have suggested either using less compression or asking women to perform self-compression. In a 2003 report, Dr. Ann Poulos and colleagues from the University of Sydney in Australia found that reducing compression did not affect breast thickness or image quality.

In this study, "each participant had an 'extra' CC film taken in addition to the normal routine films. The 'extra' film was taken with a compression force reduction of 10, 20, or 30 Newtons (N) compared to the 'normal' film," wrote Poulos (Australasian Radiology, June 2003, Vol. 47:2, pp. 121-126).

Among the roughly 120 women who underwent imaging with less compression, 24% experienced no increase in breast thickness, 17.5% had no change in thickness, and 6.2% actually had reduced thickness despite the lower compression.

"It can be inferred that the higher compression force did not increase the image quality of the films nor reduce the radiation dose, but increased the probability of a painful response," the group wrote.

Another experiment that was floated was patient-controlled compression. In a 1993 study, a group from Duke University Medical Center in Durham, NC, tested a system that allowed a woman to control her own compression using a handheld device. They reported that self-compression was significantly less painful than technologist-controlled compression, along with an overall 96% patient satisfaction with the exam (Radiology, January 1993, Vol. 186:1, pp. 99-102).

The fact that neither of these proposed techniques seem to have been picked up in clinical practice indicates that, ultimately, decisions about compression are best left up to the technologist in an open dialogue with the patient.

"In the end, it's the way that the technologist works with the patient," Rush said. "The idea is to make compression sufficient, but not more than what is needed. The compression that we need is something called 'taut.'"

While it may sound like a dichotomy, one of the keys to a taut breast is a relaxed patient. Rush said her surefire technique involves asking the patient to "slump like your mother told you never to do."

"I tell (the woman) to go limp like a rag doll. I avoid the word 'relax' since no one seems to know how to do that for more than a second. By going limp or slumping, the whole upper torso does relax. But everybody knows how to slump," she explained. "I then ask her to take in a breath and slowly begin to blow it out. The trick is that she cannot be tense upon exhalation, so the compression is contacting a relaxed, not tense, body. As she does this I apply compression slowly so that the tissue can adjust to the change in tension."

Mammographic technologist Kimberli Noviello also encourages patients to concentrate on their breath.

"When I start, I will say, 'I'm going to go slowly with the compression. You let me know if I reach your limit before I reach mine,'" said Noviello, who is also from MemorialCare Breast Center. Once the patient has given her OK, Noviello asks her to hold her breath while the image is captured.

"More often than not, they tolerate more (compression) than what I am willing to do," she added. "I think that just letting them know they have some control allows them to relax and I can position better ... get more breast tissue in the picture. Once they know that I'm not going to just slam down the compression paddle and that I will work with them ... they usually tolerate quite a bit."

Optimizing mammo equipment

Compression discomfort can also be addressed with technology. Many mammography units are outfitted with special compression maximizing features, such as resistance-based paddle adjustment, self-adjusting tilt paddles for uniform compression, or bidirectional compression for more tissue (To read more, visit the AuntMinnie.com Buyer's Guide).

A 2000 study reported success with biphasic breast compression, which relies on a paddle angled at 22.5°, followed by progressive angle reduction. The researchers found that this particular oblique shift of the paddle, and the subsequent return on the horizontal position during the compression, "allowed earlier and tighter anchoring of the breast, greater access to the patient ... and more effective breast manipulation during the first compression phase (Radiology, November 2000, Vol. 217:2, pp. 576-580).

|

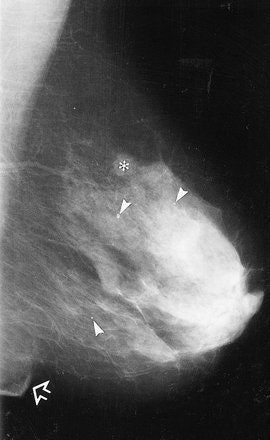

MLO images of the left breast in one patient. With (a) MC and (b) BC, the inframammary fold (open arrow) is depicted. A larger amount of the whole breast is depicted in b, on the basis of the positions of the three calcifications (arrowheads) and the round opacity (*). In addition, a cutaneous fold (solid arrows) is present in the axilla in a. Sardanelli F, Zandrino F, Imperiale A, et al, "Breast biphasic compression versus standard monophasic compression in x-ray mammography," Radiology 2000; 217:576-580.

|

Another option is mammographic accessories, specifically cushioning pads designed to deflect discomfort. Both the Laguna Hills and Tucson centers have reported success with the Woman's TouchPad MammoPad (BioLucent, Aliso Viejo, CA).

Markle led a study that tested the radiolucent cushioning pad in 512 women during routine screening. Nearly three-fourths of the women said they experienced a significant decrease in discomfort with the pad. In addition, on the breast where the pad was used, compression forced increased by 14% (The Breast Journal, July 2004, Vol. 10:4, pp. 345-349).

|

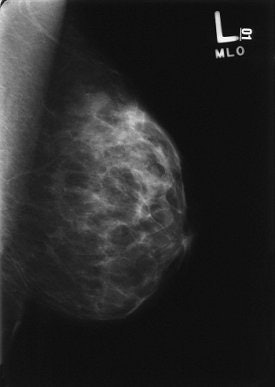

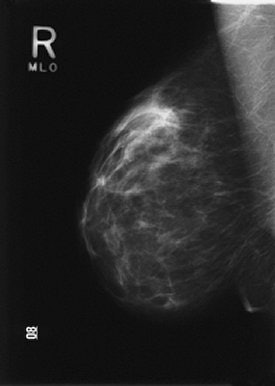

Above, left mediolateral oblique view (MLO) using MammoPad. Below, right MLO without cushioning pad. Images courtesy of BioLucent.

|

However, these accessories do come at a cost. The MammoPad sells for $250 for a case of 50 large-size pads, or $425 for a case of 100 standard-size ones. The pads are for one-time use only although the manufacturer does offer a recycling program. Patients pay for their own pads at the MemorialCare Breast Center; at the Tucson Breast Center, a single pad is provided free to every patient for every exam.

The center averages 120 patients a day, Labbe said, and the investment has been well worth it. She credited the pad use -- along with an aggressive marketing campaign by the Tucson Breast Center -- for significantly improving compliance rates at the facility. On the most basic level, it eliminates one of the most common complaints women have about mammography by softening and warming the cold, sharp-edged bucky, she said.

While these patient-friendly features are certainly beneficial, the equipment is only is good as the person using it. Dr. Francesco Sardanelli, chief of the department of radiology at the Istituto Policlinico San Donato in Milan, Italy, was the lead author on the biphasic compression study.

|

| Images obtained with and without the MaxView Breast Positioning System, which uses biphasic compression. Image courtesy of PlanMed. |

"I think (comfort) depends mainly on the level of compression reached, on the psychological relation between the technician and the patients," Sardanelli wrote in an e-mail to AuntMinnie.com.

In fact, a positive relationship between the RT and the woman can go so far as to make a woman feel that her exam is less painful. A survey of breast radiographers in European Radiology found that the communication skills of the healthcare professional, as well as their experience level, greatly influences the patient's discomfort level (October 2003, Vol. 13:10, pp. 2384-2389).

A second study, slated for presentation at the 2004 Radiological Society of North America (RSNA) meeting in Chicago, reiterates that "positive actions by radiographers during the application of compression, such as using relaxation techniques and distraction, elicited fewer pain reports" (Scientific Poster 0301BR-p).

While mammographic technologists are not there to play counselor, making that personal connection is crucial. In Tucson, the care and attention the patient receives is doubled with two RTs on hand -- one to run the computer and the other to position the patient, Labbe said. Both Rush and Noviello believe in talking the patient through the exam, letting her know every step, and encouraging her to verbally express any discomfort.

"Screening mammography is a loss leader," Rush said." So we have to perform enough of them. There's too much to do and not enough time to do it in, but the patient must trust that we care."

Compression without compromise

A few final pearls for getting everyone through a mammogram with a smile on their faces:

Outrun the rumors. It's a safe bet that the first-time screening patient will have consulted extensively with other women about the mammography experience. While a support network can be a plus, it also has a downside.

"I've had to use smelling salts on ladies who have never had a mammogram before, but people have told them terrible stories. I haven't even touched them yet, and they are ready to hit the floor," Noviello said. "I don't know why people try to scare other people by telling them horrible stories.... It's like when you are pregnant and you hear every terrible delivery story. What's the point of that?"

But just as talk got them into a state of frenzy, reassuring talk from the technologist about the exam can go a long way. "I often say, 'Give me a chance. I promise you that it won't be as bad as what you've heard,'" said Noviello. "Almost every time they say, 'Oh, my gosh, that was no big deal.'"

Think patient preparation. Breast health experts agree that screening exams should be scheduled around a woman's menstrual cycle, generally seven to 10 days after her period begins. Whether other methods are of any value, such as taking a nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID) or cutting back on caffeine, remains debatable.

"Some people will take some Advil, but we don't recommend it when we schedule patients," Markle said. "If you are the type of patient who is very sensitive, or you have fibrocystic breasts, then stay off the caffeine, but you should be doing that anyway."

Rush expressed a little skepticism about both. She pointed out that a woman who skips her daily cup of coffee is more likely to show up for her exam in an especially foul mood -- and she'll need the Advil to get rid of her caffeine headache.

Review history. The patient prep regimen at the Tucson Breast Center has nothing to do with what she ate for breakfast. Instead, the patient history form is sent directly to her along with her reminder notice, Labbe explained. A patient care assistant then accompanies the woman to the changing area and goes over that history form.

Obviously, women with breast cancer in their family, or who carry a genetic mutation, are destined to be more concerned. But Rush and Noviello cautioned that many women, at some point in their lives, have been affected by breast cancer (through a neighbor or co-worker), and that may be enough to cause distress. Reviewing the patient history form is a good opportunity to air these anxieties.

Ease the pain in the neck. A lot of the discomfort experienced during compression is actually tension in the neck. This occurs when the skin is pulled from underneath the jawline, down the neck, and to the clavicle. Rush is a fan of a technique known as the clavicular roll (credited to RT Rita Heinlein of the University of Baltimore in Maryland) for solving this issue.

"As we catch back against the chest wall and begin to apply compression, we cause additional discomfort by pulling the skin of her neck," Rush said. "To relieve this tension, drop one finger just below the clavicle, and roll just enough of the loose skin up and over the clavicle, which does not pull up any breast tissue. As the paddle catches at chest wall, let that tissue go. The result is a more relaxed neck muscle and a patient that can tolerate more compression."

Be a woman. It's no surprise that the majority of U.S. technologists who perform breast imaging exams are female. According to statistics compiled by the American Society of Radiologic Technologists (ASRT), less than 1% of mammography technologists are male. For more demographics on mammographic technologists, click here.

In a 1994 survey of 1,000 women undergoing screening mammography, the majority stated that they would go ahead with an exam if the available RT was male although their preference was for a female healthcare worker (RT Image.com, September 2, 2002, Vol. 15:35).

Is the bias unwarranted? Perhaps not, according to other research that indicated that women healthcare professionals may be more sensitive to their same-sex patients.

A 2003 survey of 198 physicians-in-training regarding their attitudes toward bilateral prophylactic mastectomy (PBM) found that male doctors were more likely than their female counterparts to recommend PBM for the prevention of breast cancer (The Breast Journal, September-October 2003, Vol. 9:5, pp. 397-402).

Another study found that physician gender was an important predictor of whether a primary care physician would recommend that an eligible patient begin mammography screening (Journal of Women's Health, January-February 2003, Vol. 12:1, pp. 61-71).

Why compress? Many women benefit simply from having compression explained to them. Rush relies on folksy analogies, such as comparing the breast to a freshly baked cake that bounces back when it's "done."

Sardanelli takes a more clinical approach. "When I realize that during the exam the patient had discomfort and/or pain, I tell her that compression is a tool for seeing better with a lower radiation exposure and that, as a consequence, a mammogram without any discomfort produces a worse image with more radiation," he said. "Generally, speaking with the women is the only tool for problem-solving in breast positioning and compression for mammography."

Offer rapid results. Waiting is the hardest part for many women; minimizing the time between the exam and the final results can alleviate that anxiety. At Markle and Noviello's center, the results of screening exams are delivered within two days. Those who require diagnostic testing get results on the same day.

The Tucson Breast Center is outfitted with full-field digital mammography (FFDM) units, so not only is the exam time shorter (three to five minutes), but the RT can check the film for quality right away. While FFDM still requires compression, it doesn't seem that way to the patients.

"We explain that it's the same four views (as a regular mammogram), but they still insist that (FFDM) hurts less," Labbe said.

Acknowledge, respect, and respond. Every breast imaging specialist is aware of the time and financial crunch imposed by the screening system. But if a benchmark of success for a screening program is compliance, then taking a few extra minutes to confer with a woman in the short term -- particularly if it's her first time -- can make all the difference over the long haul.

"I believe mammography technologists must have special characteristics," Rush said. "They must be technically competent ... while being compassionate ... when many of their patients are afraid they may receive bad news." It's important to acknowledge where the woman is emotionally -- ''to respect that she has the right to be there at that moment, and then respond to it," she said.

By Shalmali Pal

AuntMinnie.com staff writer

October 5, 2004

Related Reading

Malpractice and mammography: An exam oversold? July 15, 2004

Women fail to return for annual mammograms, June 23, 2004

Breast ultrasound experts share pearls and pitfalls, October 2, 2003

Many women get first mammogram, delay further ones, September 13, 2003

Copyright © 2004 AuntMinnie.com