The goal of every radiologist when reading mammograms is to identify the three to four breast cancers statistically known to be lurking within 1,000 screening mammograms. Achieving a high cancer detection rate while maintaining a low recall rate is a daily challenge.

Dr. Edward Sickles, professor emeritus of radiology at the University of California, San Francisco (UCSF), recently offered advice on making appropriate recall decisions with difficult screening mammograms. He spoke at the Society of Breast Imaging's (SBI) biannual postgraduate course held in Colorado Springs, CO, last month.

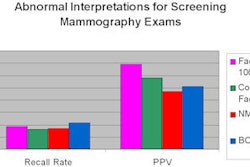

In the U.S., the average recall rate of patients requiring additional breast imaging studies is 12% or less. To achieve this, radiologists must first learn the subtle signs of malignancy, and then learn the limits of normal variation, according to Sickles.

Improving cancer detection rate

"To take full advantage of the capabilities of mammography, radiologists must search diligently not only for the typical features of malignancy, but especially for the more subtle and indirect signs," Sickles said.

Masses and calcifications are the most common indications for which to recall a patient. At UCSF, they represent approximately 80% of reasons for recall. In Sickles' experience, indirect signs represent fewer than 20%.

The most uncommon of these indications is the solitary dilated duct. Based on unpublished statistics, only 21 cases were identified out of 264,476 mammograms performed at USCF between 1985 and 2006. Of these, two cases, or 9.5%, were pathologically verified noncalcified ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS) malignancies. Sickles always recommends recall for this indication.

Focal asymmetry represents approximately 3% of nonpalpable cancers, and fewer than 1% identified are malignant based on an analysis of 85,188 consecutive screening mammograms performed at UCSF. Out of 741 cases, five were T1N0 stage I malignancies.

The most common characteristic of focal asymmetry is a space-occupying lesion seen in two different projections, with concave outward contours, usually interspersed with fat. "This is the most challenging finding at threshold for recall," Sickles observed. "Peer-review literature is robust. The patient's prior reports may give some guidance in a decision to recall."

Sickles recommends that a recall is appropriate if there is a hint of any additional findings. Radiologists should assess the lesion size versus palpability. He recommends a recall if a one-view-only finding is not included in the image field on the view not visible, and when a one-view-only finding is obscured by dense fibroglandular tissue on the view not visible.

There should be no indecision when developing asymmetry is seen: 10% to 15% of these are identified as malignant, and recall is appropriate. However, the challenge is identifying developing asymmetry. The indications are very subtle, and this represents approximately 6% of nonpalpable cancers, based on Sickles' experience.

Architectural distortion is the most frequently viewed indirect sign. This represents approximately 9% of nonpalpable cancers, and 15% to 20% are malignant. Based on unpublished data of 192,063 mammograms performed at UCSF between 1985 and 2007, of the 364 architectural distortions identified, 14.8% were malignant and 22.2% were stage II cancers. For this reason, Sickles recommends that the patient be recalled for additional imaging whenever these are seen.

Tips for identifying indirect signs

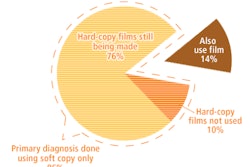

To facilitate interpretation, Sickles follows some general principles. In addition to having proper viewing conditions, he recommends use of a scribe, ideally a resident, so that radiologists can focus almost exclusively on images. Looking at text screens can detract from perception. He advocates batch interpretation for screening mammograms because a suspicious finding may be more apparent.

He also recommends the following when analyzing images:

- View right and left mammograms back to back.

- Use overall and close-in visual searches.

- Concentrate on the whitest areas on images.

- Always make a point of searching for one calcification or artifact. There always will be one, and this helps ensure that the entire image is scrutinized.

- Beware the seduction of stability.

- Annotate perithreshold findings.

- Use computer-aided detection (CAD) software as intended or do double readings. Both are shown to improve cancer detection rates.

Decrease recall rate

Radiologists should work on decreasing their recall rate only after achieving the goal set for cancer detection. Sickles strongly recommends that radiologists demand that new patients provide them with prior mammograms before a mammogram is taken. Prior mammograms not only help identify changes, but they also may show suspicious findings that are stable or have proved to be benign through biopsy.

Comparing a current mammogram with one prior mammogram will increase the likelihood of showing stability due to similar positioning and compression. A prior mammogram may also account for slight apparent changes in asymmetry due to slight differences in positioning and compression.

All prior exams should be compared with a current exam when a one-view asymmetry at threshold for recall is identified. A summation artifact may be diagnosed if comparisons can show stability due to similar position and compression on any one of several prior exams.

Sickles suggests that radiologists ask if a finding is deep, or if a breast is so dense that a finding may be obscured. If so, a recall may be justified. He suggests that when taking a close look, if blood vessels can be seen, the patient doesn't need to be recalled. "Look through the dense tissue," he recommended.

Based on his experience, Sickles said that the majority of one-view findings are predominantly summation artifacts. Citing an analysis published in 1998 of 2,023 one-view-only findings, 53.6% were summation artifacts, none of which subsequently were identified as breast cancer. If all of these patients had been recalled for additional imaging, the recall rate would have increased by 33%, from 5.1% to 6.8%, with no increase in the cancer detection rate.

When findings seem doubtful, let instinct decide. In another retrospective clinical study, Sickles determined that after a 30-month follow-up, only 1% of these exams revealed abnormal findings, and of these, only one case was malignant, with a diagnosis of DCIS.

"Subtle precursors of malignancy are difficult, if not impossible, to detect. Doing recalls or biopsies of doubtful findings has little, if any, clinical utility," Sickles said.

Gaining experience in reading mammograms will reduce the recall rate. Sickles pointed out that there is a learning curve for inexperienced readers, and the learning curve when converting from film to digital screening can last for two to three years. He encourages all radiologists to periodically review their cancer detection rates and recall rates, stating that awareness of both tends to affect performance.

"However," he concluded, "the radiologist with a very low recall rate probably isn't detecting breast cancer. Don't let your cancer detection rate decline to improve your recall rate."

By Cynthia E. Keen

AuntMinnie.com staff writer

May 13, 2009

Related Reading

ACR introduces National Mammography Database, May 7, 2009

Outcomes data add accuracy to mammography interpretations, April 20, 2009

Exceeding 'excellent’: How breast centers track quality, February 17, 2009

CAD can boost double-reading detection rate, January 22, 2009

Copyright © 2009 AuntMinnie.com