Breast lipofilling, or autologous fat injection, has been a controversial procedure for breast augmentation because of how it can affect future imaging exams. The debate has resurfaced, with conflicting studies published in the March and April issues of Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery.

Plastic surgeons from China strongly recommend that the procedure be discontinued because treated breasts may develop benign clustered microcalcifications that are indistinguishable from malignant ones on a mammography image. Plastic surgeons from France have a different opinion; they feel that radiologists who know what to look for can easily distinguish between calcifications resulting from fat necrosis and those associated with cancer (Plast Reconstruc Surg, March 2011, Vol. 127:3, pp. 1289-1299, and April 2011, Vol. 127:4, pp. 1669-1673).

Regardless of the point of view, greater diligence by radiologists is required, and the potential exists for higher medical costs from additional breast imaging exams and biopsies that may be needed to manage screening of women who have undergone this procedure.

ASPS's investigation

The lipofilling procedure consists of "harvesting" small amounts of fat obtained by liposuction from one area of the body, such as the hips or thighs, and performing one to four stages of lipoinjection as needed. Amounts range from 30 to 460 cc for breast augmentation and correction of defects, and from 1.5 to 2.5 cc for nipple reconstruction, according to the American Society of Plastic Surgeons (ASPS) Fat Graft Task Force.

In 1987, the ASPS issued a strong statement against the use of breast lipofilling, citing the risk of difficulties in the early diagnosis of breast cancer. Twenty years later, the society formed a task force headed by Dr. Karol Gutowski, clinical assistant professor of plastic and reconstructive surgery at North Shore University Health System, to assess the safety and efficacy of the procedure and to make recommendations for future research.

Noting that no high-quality randomized, controlled clinical trials had been performed, and that studies previously published in peer-review journals lacked strong data, the task force concluded that it could not make specific recommendations for clinical use of fat grafts. However, the task force also stated that autologous fat grafting was "a promising and clinically relevant research topic" and recommended that clinical trials be conducted (Plast Reconstruc Surg, July 2009, Vol. 124:1, pp. 272-280).

With respect to interfering with breast imaging, the task force wrote:

There is a potential risk of fat grafts interfering with breast physical examination or breast cancer detection; however, the limited data available suggest that fat grafts may not interfere with radiologic imaging in detecting breast cancer. ... Radiological studies suggest that imaging technologies (ultrasound, mammography, and magnetic resonance imaging) can identify the grafted fat tissue, microcalcifications, and suspicious lesions; biopsies may be performed if needed for additional clarification.

Pro: The French opinion

In one of the current studies, a multidisciplinary team of plastic surgeons and radiologists from the University of Lyon and Jean Mermoz Private Hospital analyzed the radiographic changes in breasts after augmentation by autologous fat transfer. A total of 76 patients between the ages of 21 and 55 had the procedure performed between 2000 and 2008 at the university hospital.

Postoperative mammograms of 31 patients were available for retrospective review. Pre- and postsurgery mammograms were available for 20. The 31 mammography exams were performed a median of 16.2 months following the procedures. For these patients, an average of 200.8 ± 64.8 cc of fat was injected into each breast, with 24 of the patients having only one injection per breast.

Radiographic abnormalities were identified in 14 (46%) of the 31 patients, according to lead author and plastic surgeon Dr. Michael Veber, of the University of Lyon's Léon Bérard Cancer Center, and colleagues. Benign microcalcifications were identified on five mammograms, macrocalcifications on three, cystic lesions on eight, and architectural distortion in the area of the mastopexy scar on four.

The 20 sets of pre- and postsurgery mammograms were used to compare breast tissue density and BI-RADS categorization. The researchers determined that overall breast density remained stable over time.

"Radiographic follow-up was not more difficult after lipomodeling while respecting the procedure," the authors wrote. "Interpretation was found to be easy in all the mammograms studied."

Radiographic presentation of liponecrotic "oil cysts" varies with time, according to the authors, and as long as interpreting radiologists have a thorough knowledge and understanding of these changes, they should not have difficulty evaluating the breast images.

They explained that solid nodes detectable by ultrasound but not mammography are the first abnormalities to appear. Oil cysts become visible several months later on mammography images, which may also show multiple infracentimetric nodes. Lumps of necrotic fat turn into calcifications, either round, well-defined microcalcifications developing in the vicinity of cysts, or lucent-centered macrocalcifications.

"It appears crucial for radiologists to acquire specific knowledge of lipomodeling," the authors wrote. They recommended that breast imaging specialists and plastic surgeons collaborate to avoid "alarmist falsehoods," and that radiographic follow-up of women undergoing breast lipomodeling be standardized to ensure reproducibility and improve patient safety.

Con: The Chinese opinion

Plastic surgeons from Beijing completely disagree. They wrote that when clustered microcalcifications develop following autologous fat injection, their appearance is indistinguishable from malignant calcifications. Otherwise unnecessary biopsies are performed. For this reason, they feel that the procedure should be prohibited.

Dr. Cong-Feng Wang, a plastic surgeon at Meitan General Hospital, and plastic surgeons from Peking Union Medical College Hospital retrospectively analyzed the mammograms of 48 women. These women had the breast augmentation procedure performed between July 1999 and November 2009 when they were 22 to 40 years of age.

Breast fat grafting was performed in one to four procedures at intervals of one to three months. For each procedure, between 50 and 170 mL of fat was injected into each breast.

The researchers reviewed an unspecified number of mammograms taken after the surgical procedures in the 48 women. These included exams performed as recently as 18 months post-op and up to seven years later.

|

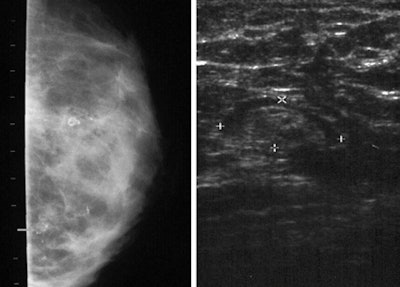

| Left: Clustered microcalcifications in the inferolateral area of the right breast cannot be distinguished from malignant calcifications. Right: Sonogram of the right axilla of the same patient shows a 1.0 x 0.8-cm lymph node. Images courtesy of Dr. Cong-Feng Wang. Reprinted with permission of the ASPS. |

Ten clustered microcalcifications had been identified in eight patients, five of which were palpable. Half of the clustered microcalcifications were located in the middle area of the breast.

Because the images of the microcalcifications were indistinguishable from malignant ones, biopsies were performed on each patient. None were cancers. Fat necroses were pathologically confirmed for all.

"Biopsy is compulsory in patients with clustered microcalcifications," the authors wrote. "We cannot wait to see the evolution of such symptoms."

The authors did not question the aesthetic success of the procedure for breast augmentation. However, they are deeply concerned about the lifetime breast health of these women. They contend that mammographic confusion, the need for unnecessary biopsies, and the potential to misinterpret a malignancy are reasons "the method should continue to be prohibited."