Studies released at this week's European Breast Cancer Conference (EBCC) in Vienna focused on breast screening and how it relates to a treatment and outcome. Researchers discussed the link between breast density and cancer recurrence, whether early screening reduces mortality, and when MRI should be added to breast screening.

Breast density and cancer recurrence

Women older than 50 with breasts that have a high percentage of dense tissue are at greater risk of breast cancer recurrence, according to Swedish researchers.

Dr. Louise Eriksson and colleagues from the Karolinska Institutet in Stockholm studied mammograms and outcomes for 1,774 postmenopausal women between the ages of 50 and 74. These women were part of a larger study of all women with breast cancer diagnosed between 1993 and 1995 in Sweden.

The team found that if a woman has a percentage density of 25% or more at diagnosis, she has an almost twofold increased risk of local recurrence in the breast and surrounding lymph nodes, compared with women with a percentage density of less than 25%.

However, density does not appear to increase the risk of distant metastasis and has no effect on survival, Eriksson's team found. And although mammographic density is one of the strongest risk factors for breast cancer, it doesn't seem to influence tumor development in any specific way, the group said.

Screening saves lives

A Dutch study of the effectiveness of breast cancer screening demonstrated that population-based mammography programs save a significant number of lives, adding fuel to the debate about whether national screening programs are necessary (some argue that because treatment for breast cancer is now so effective, the chances of surviving are as good as if the tumor had been detected early via a screening program).

Rianne de Gelder, a doctoral student and researcher at Erasmus University Medical Center in Rotterdam, led a team that found that adjuvant therapy reduced deaths by an estimated 13.9% in 2008 compared to no treatment. But they also found that screening every two years reduced deaths by an additional 15.7%.

The group used a computer modeling technique called microsimulation to show that adjuvant treatment reduced deaths from breast cancer from 67.4 per 100,000 women-years to 57.9. With the addition of screening every two years between the ages of 50 and 75, the death rate fell to 48.8 per 100,000 women-years, meaning that adjuvant therapy combined with screening reduced deaths by a total of 27.4%, de Gelder said.

If screening were extended to women between the ages of 40 and 49, deaths would be reduced further to 5.1%, producing a total reduction in breast cancer deaths of 31.1%, compared to no treatment and no screening for women between 40 and 75.

When is MRI screening appropriate?

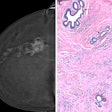

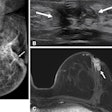

Although adding MRI to standard breast cancer screening approaches is expensive, it could be cost-effective for women who have a familial risk of developing the disease, researchers from the Netherlands found.

Dr. Sepideh Saadatmand of the Erasmus University Medical Center in Rotterdam and colleagues conducted a cost-effectiveness analysis of 1,597 women between the ages of 25 and 70 who were enrolled in the Dutch MRI Screening Study between 1999 and 2007, and who had an estimated cumulative lifetime risk of between 15% and 50% for developing breast cancer before the age of 70. The women were screened by way of a clinical breast examination every six months and an annual mammography and MRI exam.

Although adding MRI to the screening process reduced breast cancer mortality by 24%, Saadatmand's team found that it cost approximately three times as much for every estimated one year of life saved. Meanwhile, just using annual screening mammography and clinical breast examination alone reduced breast cancer deaths by 20%.

Therefore, adding MRI to screening programs for all women with a cumulative lifetime risk of breast cancer of 15% to 50% "is highly effective, but possibly too expensive," except for certain subsets of women, the group concluded.

Cancer cells in blood predict survival

Finding circulating tumor cells in the blood of women with early breast cancer -- after surgery but before the start of chemotherapy -- may provide useful information about their chances of survival, according to German researchers.

Dr. Bernadette Jäger of the Ludwig Maximilian University Hospital in Munich and colleagues analyzed the numbers of circulating tumor cells in the blood of 2,026 women; all had a complete resection of their primary tumor before starting chemotherapy. The cells were detected in 21.5% of women, the group found, which is a much lower rate than what is usually seen in metastatic breast cancer.

Although detecting the number of circulating tumor cells in blood is difficult, it is less invasive than collecting bone marrow, which is another way to evaluate them, Jäger said. If the presence of the cells could be used to monitor the efficacy of treatment, it could also help doctors determine the best chemotherapy regime for each patient, she concluded.