The addition of ultrasound or MRI to annual mammography screening in women with an increased risk of breast cancer and dense breast tissue resulted in the detection of more breast cancers, according to a study in the April 4 issue of the Journal of American Medical Association.

Researchers from 21 institutions affiliated with the American College of Radiology Imaging Network (ACRIN) found that annual ultrasound exams may detect small, node-negative breast cancers that are not seen on mammography, while MRI can uncover additional breast cancers missed by both mammography and ultrasound.

The study, led by Dr. Wendie Berg, PhD, professor of radiology at the University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine and Magee-Womens Hospital, concluded that supplemental ultrasound increased cancer detection by an average of 4.3 cancers per 1,000 women per year over each of three years of screening, while MRI further increased cancer detection with a supplemental yield of 14.7 cancers per 1,000 women.

However, Berg and colleagues also cautioned that there is an increased risk of false positives and unnecessary biopsies with the addition of ultrasound and MRI screening (JAMA, Vol. 307:13, pp. 1394-1404).

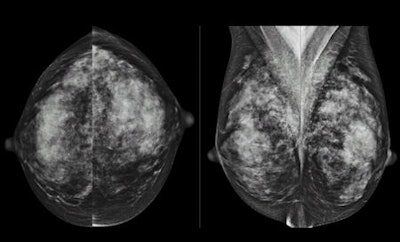

Dense breast issues

Speaking with AuntMinnie.com, Berg said looking for a cancer in women with dense breasts "is like looking for a polar bear in a snowstorm, where [the cancer] is hidden by the dense tissue. While digital mammography improves on that a little bit, it is still a problem even with the best mammograms. There is a lot of tissue that is the same whiteness as the cancer itself.... In fact, more than half of cancers in women with dense breasts will not be seen on mammograms."

Berg led a study in which a total of 2,809 women at 21 sites with dense breasts and at least one other risk factor for cancer agreed to have three annual independent screenings with mammography and ultrasound from April 2004 to February 2006. The median age at enrollment was 55 years, and approximately 54% of the women had a personal history of breast cancer.

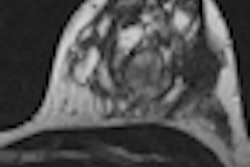

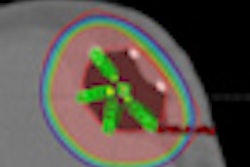

After three years of both mammography and ultrasound screenings, 612 women chose to undergo an MRI scan. As a reference standard, researchers used a combination of biopsy results that showed in situ infiltrating ductal carcinoma, or infiltrating lobular carcinoma in the breast or axillary lymph nodes, and at least a 12-month follow-up.

Of the 2,662 women who underwent 7,473 mammogram and ultrasound screenings annually over three years, 110 of the subjects had 111 breast cancer events. Mammography detected 59 cancers (53%), including 33 (30%) cancers that were detected by mammography only.

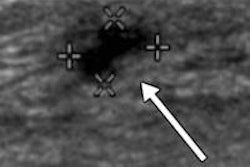

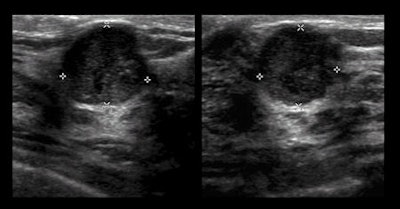

Ultrasound's benefit

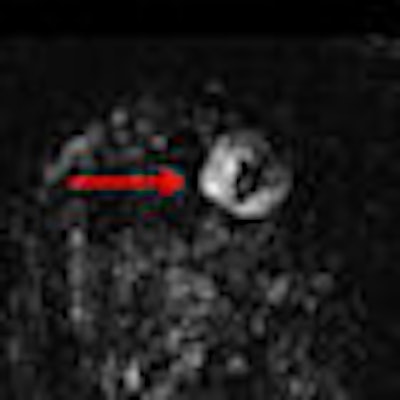

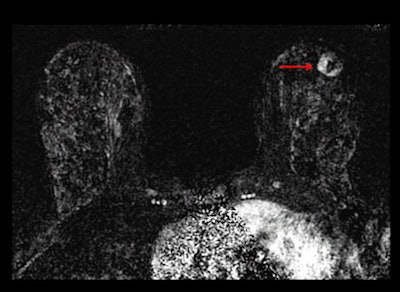

There were 32 cancers (29%) that were discovered by ultrasound alone, while nine cancers (8%) were found exclusively by MRI after both mammography and ultrasound failed to detect the abnormalities. A total of 11 cancers (10%) were not detected by any of the three imaging modalities, including nine cancers (8%) detected clinically in the interval between screenings.

"This low interval cancer rate across the three years of mammography plus ultrasound is very encouraging," Berg said.

A total of 16 of 612 women (2.6%) in the MRI substudy were diagnosed with breast cancer. Among the 4,814 screenings in the second and third years combined, 75 women were diagnosed with cancer.

Supplemental ultrasound also increased cancer detection with each screening beyond mammography by uncovering an additional 5.3 cancers per 1,000 women in the first year and 3.7 more cancer cases per 1,000 per year in each of the second and third years of screening. Sensitivity for mammography plus ultrasound was 76%, specificity was 84%, and positive predictive value of biopsy was 16%.

Mammography alone achieved sensitivity of 52%, specificity of 91%, and positive predictive value of biopsy of 38%.

The number of screens needed to detect one cancer was 127 for mammography, 234 for supplemental ultrasound, and 68 for supplemental MRI after negative mammography plus ultrasound screening results.

MRI diagnosed breast cancer in 16 women (3%) from the study group, which translated into a supplemental yield of 14.7 per 1,000. Sensitivity for MRI and mammography plus ultrasound was 100%, specificity was 65%, and positive predictive value of biopsy was 19%.

False-positive warning

"It is very important for women to be aware of the risk of false positives from any extra testing," Berg said. "For ultrasound, it was about 7% of women who had some extra testing. We expect about 10% from a mammogram, but this was in addition to that 10%. About 5% will need a biopsy due to ultrasound."

Berg said the results of increased cancer detection with the three imaging modalities should be applicable to women with more than one risk factor and who have dense breasts. "We expect there would be a slightly lower rate of cancer in the population who does not have another risk factor," she added.

Berg and colleagues also noted in their study that despite the higher sensitivity, the addition of screening MRI rather than ultrasound to mammography in broader populations of women at intermediate risk with dense breasts "may not be appropriate, particularly when the current high false-positive rates, cost, and reduced tolerability of MRI are considered."

In addition, researchers found that that many women simply declined an MRI, even if it were offered at no cost.

"It is not a very well-tolerated screening test," Berg said. "Even though it is a very sensitive test, it is also very expensive, it requires contrast injections, and women are claustrophobic. All of these issues need to be considered in screening. Most women do not have cancer, so you don't want to put them through a lot of extra stress, cost, and all these other issues if you can help it."

ACS recommendations

Currently, the American Cancer Society's guidelines recommend MRI in high-risk women. There also are certain women who have a known or suspected genetic mutation that puts them at risk. Other risk factors include prior radiation therapy to the chest before the age of 30, or a prominent family history of breast cancer that gives them at least a 20% to 25% or greater lifetime risk of breast cancer.

"In that group we recommend MRI, but there is a much larger group of women who have maybe only a personal history of breast cancer, a prior atypical biopsy, and have dense breasts, or just have extremely dense breasts," Berg said. "Those are all women who are at moderately increased risk, where we know the mammogram is limited, but we have not had consensus about what to do. If you can get an MRI and you want it, and your insurance will cover it, MRI is still the most sensitive test, but it is not something that would be widely accepted by women."

The study was funded by the Avon Foundation and grants from the U.S. National Cancer Institute and conducted through the American College of Radiology Imaging Network (ACRIN 6666).