Despite significant increases in the number of cases of early-stage breast cancer detected since the 1970s, screening mammography has only marginally reduced the rate at which women present with advanced cancer, according to new research published in the November 22 issue of the New England Journal of Medicine.

In a study sure to add fuel to the already heated debate over the benefits and harms of screening mammography, researchers from Oregon Health & Science University concluded that their data raise "serious questions about the value of screening mammography" -- despite also finding that death rates dropped nearly 30% over this time period.

"Although it is not certain which women have been affected, [our study data suggest] that there is substantial overdiagnosis, accounting for nearly a third of all newly diagnosed breast cancers, and that screening is having, at best, only a small effect on the rate of death from breast cancer," wrote lead author Dr. Archie Bleyer and colleague Dr. H. Gilbert Welch (NEJM, November 22, 2012, Vol. 367:21, pp. 1998-2005).

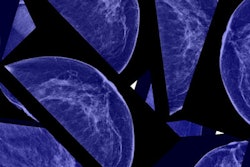

Bleyer and Welch used Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) data to examine trends from 1976 to 2008 in the incidence of early-stage breast cancer (ductal carcinoma in situ [DCIS] and localized disease) and late-stage breast cancer (regional and distant disease) among women 40 years or older.

The authors used the following steps to calculate the number of additional women with a diagnosis of early-stage cancer, as well as the reduction in the number of women with a diagnosis of late-stage cancer:

- Determined a baseline incidence before screening, choosing the three-year period between 1976 and 1978. During this period, the incidence of breast cancer was stable and few cases of DCIS were detected; these findings are compatible with the limited use of screening mammography at that time.

- Calculated the surplus (or deficit) incidence relative to the baseline in each subsequent calendar year, basing the estimate of the current incidence of breast cancer on the three-year period from 2006 through 2008 (other research has described the end of the effect of hormone-replacement therapy at 2006; Bleyer and Welch cut observed incidence each year from 1990 through 2005 if it was higher than the estimate of the current incidence).

- Translated data on the change in incidence to data on nationwide counts.

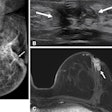

The authors found that introducing screening mammography in the U.S. has doubled the number of cases of early-stage breast cancer detected each year, from 112 to 234 cases per 100,000 women -- for an absolute increase of 122 cases per 100,000 women. At the same time, the rate at which women present with late-stage cancer has decreased by 8%, from 102 to 94 cases per 100,000 women, for an absolute decrease of eight cases per 100,000 women.

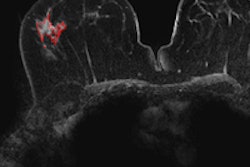

After cutting out excess incidence associated with hormone-replacement therapy and adjusting for trends in the incidence of breast cancer among women younger than 40 years of age, Bleyer and Welch estimated that breast cancer was overdiagnosed (i.e., tumors were detected on screening that would never have led to clinical symptoms) in 1.3 million U.S. women in the past 30 years.

"We estimated that in 2008, breast cancer was overdiagnosed in more than 70,000 women; this accounted for 31% of all breast cancers diagnosed," the team wrote.

And 30 years of mammography screening did little to affect the incidence of regional and distant late-stage breast cancer, Bleyer told AuntMinnie.com.

"Our study found that there was only an 8% increase in diagnosis of late-stage cancer, while early-stage cancer detection doubled," he said. "What we hope to see is that for every woman whose cancer is detected early, there's one less woman whose cancer is detected late. But that's not what happened, which suggests that there's something wrong with screening."

Bleyer and Welch found that over the same 30-year time frame, the rate of death from breast cancer decreased by 28%. But they attributed this decrease to a combination of the effects of screening mammography and better treatment.

"Whereas the decrease in the rate of death from breast cancer was 28% among women 40 years of age or older, the concurrent rate decrease was 42% among women younger than 40 years of age," Bleyer and Welch wrote. "In other words, there was a larger relative reduction in mortality among women who were not exposed to screening mammography than among those who were exposed. We are left to conclude, as others have, that the good news in breast cancer -- decreasing mortality -- must largely be the result of improved treatment, not screening."

Is it really disease?

What if what screening mammography finds is not, in fact, disease? Bleyer asked.

"We don't know what this is, what we're calling 'cancer' in early diagnosis," he told AuntMinnie.com. "The majority of the women diagnosed with cancer at screening don't get sick from it. So we're making something that isn't a problem into a problem."

There's no doubt, however, that breast cancer screening is an emotional topic, Bleyer said.

"Cancer is the most feared disease," he said. "And women believe that screening saved their lives. But our study suggests that the good news in breast cancer -- decreasing mortality -- must largely be the result of improved treatment, not screening."

Taking another view, Dr. Daniel Kopans, of Massachusetts General Hospital, countered that the thesis of breast cancer incidence returning to the baseline present before screening began is flawed. Bleyer and Welch contend that because the rate did not return to what they claim it should be, the difference between the actual rate and their suggested baseline represent cancers that would never progress, Kopans wrote AuntMinnie.com in an email.

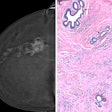

"Bleyer and Welch chose to dilute the data by including DCIS along with invasive breast cancers," Kopans said. "There is legitimate importance in developing a better understanding of DCIS, and many investigators are trying to do this. But grouping DCIS with invasive breast cancers is simply done to exaggerate their conclusions. They also neglected to point out that if they looked at invasive cancers alone, and used a valid baseline for invasive cancers that increased by 1% per year from 1980 to 2008, they would have found that there were 100 per 100,000 cases of invasive cancer in 1980 -- and this should have reached at least 132 per 100,000 by 2008 simply based on the 1% per year trend from 1940."

Bleyer and Welch ignore the fact that a reduction in advanced-stage disease is not required to have a reduction in deaths from screening, and they do not take into account the fact that new cohorts of women begin screening each year, so their "prevalence" cancers will keep the "incidence" well above the baseline, Kopans told AuntMinnie.com.

"Overestimates of 'overdiagnosis' are smoke and mirrors," Kopans wrote. "There is no question that there are breast cancers that may not be lethal, but this is not the fault of screening. ... The bottom line is that ... the death rate from breast cancer, which had been unchanged for over 50 years, suddenly began to decline in 1990 shortly after the start of screening in the U.S."

In a statement, the American College of Radiology (ACR) weighed in as well, calling the study "deeply flawed and misleading."

"The authors suggest that the baseline incidence of breast cancer would have increased by 0.5% each year, when in fact, the data show that it would likely have increased by twice that amount," the ACR said. "Misleading articles, based on faulty assumptions and methodology, are counterproductive. If such misinformation is used to determine screening guidelines and recommendations, the cost may be lost lives."

Bleyer and Welch acknowledged that their study has limitations:

- Overdiagnosis can never be directly observed and, thus, can only be inferred from reported incidence.

- The ability to remove the effect of hormone-replacement therapy is imprecise.

- They made some assumptions about the pattern of underlying incidence, i.e., the incidence of breast cancer that would have been observed in the absence of screening.

- The best-guess estimate of frequency of overdiagnosis did not distinguish between DCIS and invasive breast cancer.

- Some might argue that the best-guess estimate of the frequency of overdiagnosis was based on the wrong denominator: Rather than the number of all diagnosed breast cancers, it should have been the number of screening-detected breast cancers.

But what the study findings offer is a macro view, Bleyer and Welch wrote. Instead of focusing on a selected group of patients, a specific protocol, or a single point in time, it considers national data over a period of three decades. Breast cancer detection has got to shift from state of the art to "state of the science," Bleyer said.

"Instead of guessing at what we're seeing [on a mammogram] and getting it biopsied, we have to do a better job," he said. "That's one of the things this study is trying to do -- open up a line of research that could help determine what exactly the images are calling positive."