A substantial number of patients 65 years or older with limited life expectancy still receive routine screenings for cancer, despite the fact that they are unlikely to benefit from treatment procedures, according to a study published online August 18 in JAMA Internal Medicine.

The study, led by Dr. Trevor Royce from the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, raises questions about the actual benefits of screening for older patients and to what degree "unnecessary" screening adds to the overall cost of healthcare.

The aim of the U.S. government's Healthy People 2020 initiative is to increase the number of individuals who receive cancer screening based on the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) guidelines, Royce and colleagues noted. However, some public health experts have questioned whether cancer screening truly benefits patients with limited life expectancy.

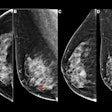

The researchers reviewed the rates of prostate, breast, cervical, and colorectal cancer screening in 27,404 patients 65 years of age or older, using data from the National Health Interview Survey from 2000 through 2010 (JAMA Intern Med, August 18, 2014).

The study cohort was segmented into four groups, from low risk to very high risk, based on nine-year mortality rates. Low mortality risk was defined as less than 25% and very high mortality risk was defined as 75% or greater.

Among patients in the very high mortality risk group, prostate cancer screening was most common, with 55% of subjects receiving this type of screening. For women who had a hysterectomy for benign reasons, 34% to 56% had received a Pap screening test within the past three years.

| Screening rates | |||

| Cancer type | Overall rate | Low mortality risk group | Very high mortality risk group |

| Prostate | 64% | 70% | 55% |

| Breast | 63% | 74% | 38% |

| Cervical | 57% | 70% | 31% |

| Colorectal | 47% | 51% | 41% |

Screening for prostate and cervical cancers decreased in more recent years, compared with the totals in 2000. In addition, older age was associated with less screening for all cancers, Royce and colleagues found.

As for socioeconomic factors, patients who were married, had more education, had insurance, or had a usual place for care were more likely to be screened.

"These results raise concerns about overscreening in these individuals, which not only increases healthcare expenditure but can lead to patient net harm," the authors wrote. "Creating simple and reliable ways to assess life expectancy in the clinic may allow reduction of unnecessary cancer screening, which can benefit the patient and substantially reduce healthcare costs."

In a related commentary, Dr. Cary Gross, from Yale University School of Medicine, wrote that it is particularly important to question screening strategies for older persons.

"Patients with a shorter life expectancy have less time to develop clinically significant cancers after a screening test and are more likely to die from noncancer health problems after a cancer diagnosis," he wrote. "In addition, older persons face a higher risk of complications from procedures such as screening colonoscopy."

Gross co-authored a study in the Journal of the National Cancer Institute in July that claimed Medicare is spending millions of dollars on unproven breast imaging technologies that do not benefit older women.