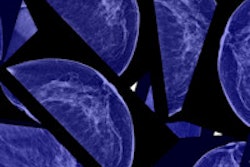

Women with a history of a false-positive screening mammogram have a nearly 40% increased risk of breast cancer for at least a decade afterward, according to a study published online in Cancer Epidemiology, Biomarkers and Prevention, a journal of the American Association for Cancer Research (AACR).

Led by Louise Henderson, PhD, of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, the researchers used Breast Cancer Surveillance Consortium data from 1994 to 2009 and identified women ages 40 to 74 years. The study included 2.2 million screening mammograms performed in 1.3 million women (Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev, December 2, 2015).

They focused on screening mammograms that resulted in three types of findings: a false positive with recommendation for additional imaging, a false positive with recommendation for biopsy, or a true negative with no cancer within one year following the examination.

Women between the ages of 40 and 49 had the highest proportion of false-positive exams with recommendations for additional imaging or biopsy, the researchers found. In addition, a higher proportion of false-positive exams were found among women with heterogeneously or extremely dense breast tissue, compared with those who had almost entirely fatty or scattered fibroglandular tissue.

The study showed that women with a history of a false-positive screening mammogram were at increased risk of developing breast cancer. Those recommended for additional imaging had a 39% higher risk and those recommended for biopsy had a 76% higher risk, compared with women with a true-negative mammogram.

When the researchers stratified the exams by breast density, they found similar increased risk percentages with additional imaging and biopsy recommendations for women with scattered fibroglandular, heterogeneously dense, and extremely dense breast tissue. But among women with almost entirely fatty breasts, the risk was even higher: 70% more than for women with a true-negative mammogram result.

"Our finding that breast cancer risk remains elevated up to 10 years after the false-positive result suggests that the radiologist observed suspicious findings on mammograms that are a marker of future cancer risk," the researchers wrote. "Given that the initial result is a false positive, it is possible that the abnormal pattern, although noncancerous, is a radiographic marker associated with subsequent cancer."

What do these findings suggest for clinical practice? Perhaps false-positive mammography history should be incorporated into breast cancer risk prediction models, according to Henderson and colleagues.

"This information should be considered for inclusion in risk prediction models to better stratify women into risk categories that may be used to personalize breast cancer screening and primary prevention strategies for individual women," they wrote.