Whichever side of the breast screening debate you sit on, you cannot dispute that digital mammography is the most established technology across Europe.

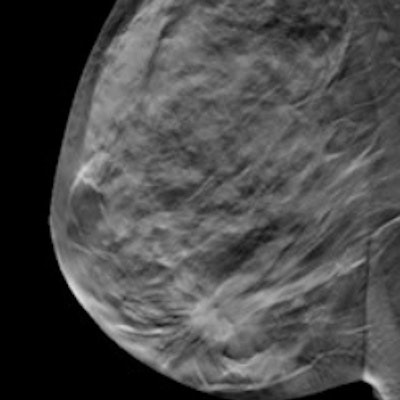

Radiation dose, the impact of false-positives, overdiagnosis, and suitability for differing breast densities are issues that continue to challenge the use of digital mammography in screening. Therefore, healthcare technology vendors have developed technology that could offer an alternative to mammography. Below, we review these emerging products and assess their potential impact and market viability in the context of breast screening in Europe.

Digital breast tomosynthesis (DBT) has long been the presumed successor to digital mammography. Yet adoption in Europe has been very slow, especially if compared with the U.S., in which over 50% certified breast imaging facilities have DBT systems installed. While the clinical debate over its suitability is far too lengthy for this summary, a growing body of evidence suggests that DBT does offer improvements in cancer detection and reduced recall rates.

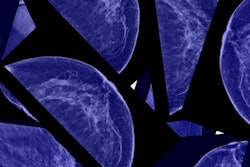

However, significant questions remain in how DBT should be used: in addition to conventional digital mammography, in which the combined radiation dose is increased; or as a standalone, in which a "synthetic" two-dimensional (2D) mammography image is created from a compound of the multiple images acquired for 3D DBT. No clear and obvious outcome has yet been reached in answering this question. The time taken for DBT images to be read versus digital mammography also needs due consideration, especially given the shortage of radiologist reading resources across European markets. While artificial intelligence may have a role to play in augmenting DBT reading for screening, it is still early days and some way off on large scale adoption.

From a market access perspective, DBT is a prime candidate. Several commercially available products are already certified, and upgrades to existing digital mammography systems are often possible. DBT pricing also is not a substantial premium on standard digital mammography. Assuming health providers can be convinced of the clinical benefits of DBT, economics should not be the limiting factor for adoption.

Automated breast ultrasound (ABUS) has, like DBT, also been available for some time but has had limited impact so far. While awareness that conventional digital mammography may not be as effective in screening for women with dense breast tissue has increased, adoption has been slow. The "European Breast Guidelines" from the European Commission also do not support ABUS use in screening, suggesting a "conditional recommendation against the intervention" for use of ABUS instead of digital mammography for women with dense breast tissue, due to a "scarcity of evidence."

From a market perspective, barriers to entry also are higher versus DBT. ABUS systems will need to be purchased in addition to digital mammography as the recommended standard; with prices almost rivaling digital mammography systems, providers will be paying significantly more. Thus, any ABUS purchasing decision for screening requires a robust clinical and economic feasibility study to justify the additional cost. It is also notable that few vendors have developed ABUS systems, with only a handful available in Europe today. "Hybrid" digital mammography, combining digital mammography and ABUS in a single system, may offer a solution to the economic challenges. However, one system is commercially available in Europe (Cape Ray) with other systems supposedly in development. Therefore, adoption of ABUS in Europe for screening has some way to go and, even then, is more likely to be used in addition to digital mammography, as opposed to a replacement.

From a clinical perspective MRI has shown impressive results in clinical specificity and sensitivity for breast cancer detection, especially for cases where the use of mammography and ultrasound has been equivocal. However, MRI is almost always considered as an addition to, rather than a replacement for, digital mammography in Europe today. Constraints of cost and availability for MRI mean it is reserved only for high-risk patients; only in Austria and Italy is MRI more commonly offered for regular screening in addition to digital mammography. Given MRI resource constraints, it is hard to see MRI realistically becoming a significant challenger to digital mammography anytime soon.

| Comparison of 'challenger' breast screening technologies | ||||

| Measure | DBT | ABUS | MRI | 'Challenger' tech |

| Commercially available in EU | Yes | Yes | Yes | -- |

| Cost of system | 200K-275K euros | 175K-250K euros | 1M+ euros | 10K-300K euros |

| Clinical evidence for screening | Mid/high | Mid/low | Mid | Low |

| No. of vendors with product | 5+ | 3 | 5+ | < 5 per segment |

| Maturity of technology | >+++ | + | ++++ | + |

A host of other challenger technologies also are in development and being targeted at breast screening. Perhaps the most promising are those that utilize photoacoustic imaging; combining laser pulses and sound waves to identify regions of high vascular density and corresponding high hemoglobin concentration thought to occur around tumors and also to discern between malignant and benign masses. While the lack of radiation with this approach is a clear positive, most systems are still in development or undergoing certification. Moreover, the price of these systems so far is mooted to be the same or higher than conventional digital mammography.

Other contenders include using systems based on piezoelectric (to characterize lesions by stiffness) and thermography (metabolic assessment of tumors) methods. Early prototypes have been focused on deployment for prescreening and triage in developing countries, where access to mammography is limited. While these are unlikely to replace digital mammography, their simpler technology could open opportunities for home use and prescreening. There is some way to go in terms of clinical validation and economy of scale to get to this level of consumer adoption, but long-term they do offer some promise for more regular prescreening, thus reducing false positives and unnecessary radiation from mammography.

Stephen Holloway is a principal analyst at Signify Research, a U.K.-based independent supplier of market intelligence and consultancy to the global healthcare technology industry.

Originally published in ECR Today on 27 February 2019.

Copyright © 2019 European Society of Radiology