Low-value breast cancer screenings are rare among members of the U.S. Veterans Health Administration, with some 97% of screenings complying with established guidelines, according to research published October 22 in JAMA Network Open.

A team led by Dr. Linnaea Schuttner from the Veterans Affairs (VA) Puget Sound Health Care System in Seattle also found that low-value cervical and colorectal cancer screenings were rare in this population, but more than one-third of patients screened for prostate cancer were tested outside of clinical practice guidelines.

"Our study suggests that there still may be women that are being screened outside of clinical practice guidelines and for whom the benefits of screening may be outweighed by the risk," Schuttner told AuntMinnie.com. "In systems that deliver more care to a higher proportion of female patients, the absolute number of low-value mammographies may be much higher."

Cancer screenings are considered low value if the care provided comes without benefit or if the potential harms outweigh the benefits. Some guidelines recommend stopping cancer screenings when life expectancy falls below a threshold, such as 10 years, as increasing age, greater illness burden, or lower life expectancy can reduce the value of screening.

However, more than 50% of adults with reduced life expectancy report ongoing cancer screening, the researchers said. This can lead to excess and unnecessary costs, workload, and downstream cascades of care that could have been avoided.

Schuttner et al wanted to describe the prevalence of low-value screening and what factors caused it in four common low-value cancer screenings within the Veterans Health Administration, including breast, cervical, colorectal, and prostate.

They looked at data from 5,993,010 veterans with an average age of 63.1 years. Of these, 91% of the study population was male. Meanwhile, 75.7% of the veterans included in the study were non-Hispanic white and 17.2% were non-Hispanic Black.

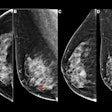

Of the 469,045 women included in the study, 21,930 at average risk (4.7%) underwent breast cancer screening. The study authors included women who had a mammogram.

Low-value testing was found in 633 (2.9%) of the 21,930 women screened for breast cancer. The team wrote that patients were less likely to receive low-value tests if they had greater comorbidity, frailty, or copays. They also had lower odds of receiving a low-value test if they attended top-performing clinics for care continuity, with an odds ratio of 0.46 (p = 0.004).

Schuttner said while mammography makes up a small part of the team's findings, it helps to create a picture of overall cancer screening behavior.

The researchers also found that out of the 4,647,479 men screened for prostate cancer, 350,705 (7.5%) received a low-value test.

Schuttner and colleagues said low-value cervical or breast cancer screening may occur infrequently given that there are fewer women veterans compared with men in the Veterans Health Administration system, with factors differing by test procedure.

"With rare on-site mammography facilities, breast cancer screening off-site referrals may be particularly burdensome to women with more comorbidities, leading to less frequent low-value testing," the study authors wrote.

However, low-value cervical cancer testing may occur as a byproduct of frequent clinic visits for women with higher comorbidities, they added. Patient race and ethnicity, sociodemographic factors, and illness burden were linked to greater chances of receiving low-value tests among screened patients.

For example, non-Hispanic Black patients and patients who were Hispanic or other races or ethnicities were less likely to receive low-value cervical cancer tests (p < 0.001 and = 0.002, respectively). However, those same patients were more likely to receive low-value colorectal cancer tests (p < 0.01 and 0.01, respectively).

Schuttner said these results can help make clinicians more aware of screenings that might not be appropriate for all patients. Strategies that could be applied to counter this include emphasizing the adverse risks from testing, communicating with patients about focusing on their other health needs when they aged out of screening, or tailoring performance metrics to target more appropriately who and who might not benefit from screenings.

Schuttner told AuntMinnie.com that the team would like to work next on developing clinical interventions that help increase the quality of care. This includes focusing on what patients want and matching this to what would benefit patients from an overall health and patient-centered outcome perspective.