Researchers in Arizona are building a virtual library of 3D hearts in a bid to improve the matching process between heart transplant donors and recipients, and to make the best use of the perpetually tight supply of donor organs.

In a presentation at the American Heart Association (AHA) scientific sessions earlier this month, Jonathan Plasencia, a PhD student in Arizona State University's Image Processing Applications Laboratory, showed how the library has transformed what was a crude donor-recipient matching technique based mostly on patient weight into a more nuanced and accurate 3D matching system based on a library of images of normal children's hearts.

Jonathan Plasencia, PhD student at Arizona State University.

Jonathan Plasencia, PhD student at Arizona State University.Plasencia, along with Justin Ryan, Jacob Lindquist, and colleagues from Phoenix Children's Hospital and St. Joseph's Hospital in Phoenix, launched a library of 3D CT and MR images of the hearts of healthy children who weighed up to 99 lb. The library has since grown to 50 datasets and now includes the hearts of children weighing as much as 220 lb.

"One thing that clinicians like is to take a heart and look at it with the potential donor and compare it to the patient," Plasencia said. "We wanted to build a library of 3D hearts so the surgeon can take them and kind of overlay them."

Never enough donors

There are never enough donor hearts for children who need transplants, and serious complications can ensue when the donor heart is too large or too small for the recipient. However, extended time spent on the wait list increases mortality for transplant recipients and leads to healthy donor organs languishing unused until they must be discarded.

Currently, institutions match donors and recipients using a simple formula based on the donor-to-recipient body weight ratio. But the crude calculation doesn't consider heart geometry or organ size, leading to significant mismatches. Even so, recent literature suggests that the donor-recipient weight-ratio range may be safely expanded.

"We've been developing a project to quickly take different heart sizes and correlate them to weight," Plasencia said.

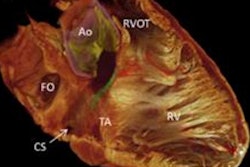

3D heart images from healthy volunteers in the library were used to predict the best donor body weight to ensure a successful transplant. The calculations used linear fit of the heart and total heart volume on echocardiography to predict donor heart volumes and the ideal donor weight for patients weighing up to 50 lb. Pre- and post-transplant images of three infants who underwent transplantation were then reconstructed in 3D to analyze the success of the method in matching hearts to recipients.

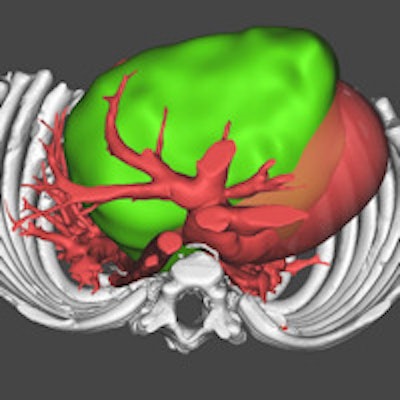

When the method is eventually used in clinical practice, the patient who needs a transplant will come in for initial imaging and 3D reconstruction of heart images, as well as recording of the patient's heart volume, Plasencia explained.

"We will then go to the healthy heart library and use the regression model to calculate the ideal [donor] weight and corresponding heart volumes and do a 'virtual transplant,' " by overlaying 3D images of the patient and donor hearts, he said. "For the virtual transplant, we take a normal-looking heart of the same volume and that would be our ideal. Of course, when we say our ideal volume, we don't know if it's clinically ideal yet -- we still have to do validations to prove that."

The results presented at the AHA conference showed that using 3D reconstructions in the library allowed the group to accurately identify appropriate donor heart sizes in three transplant cases. Patient A presented with cardiomegaly, so the donor-recipient weight ratio was likely outside the limits of some centers, according to the researchers. Because of the cardiomegaly, the heart that was eventually transplanted was smaller than the 1:1 ratio targeted by the system, but it was adequate for the patient.

Prior studies suggest that in the months following transplantation, oversized hearts shrink and undersized hearts grow. Similarly, in this study, imaging results one week after the transplant showed that the downsized graft became larger (patient A) and the upsized grafts (patients B and C) shrank, Plasencia said.

| Patient outcomes using 3D heart library matching technique | |||||

| Patient | Recipient weight (lb) | Donor weight (lb) | Donor/recipient weight ratio | Donor/recipient heart volume ratio | Post-/pre-transplant donor volume ratio |

| A | 5.69 | 6.39 | 1.12 | 0.33 | 1.47 |

| B | 8.38 | 30.86 | 1.68 | 1.72 | 0.65 |

| C | 17.92 | 41.89 | 2.34 | 0.53 | 0.53 |

The matching technique provided personal weight range listings and postsurgical conformations for the virtual transplant data used in the patients, Plasencia said.

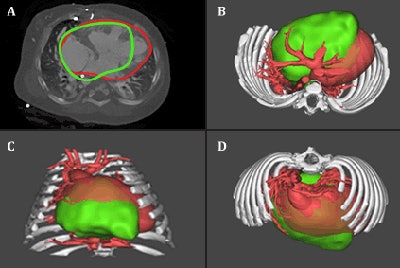

Pretransplant image of patient C (top left) and 3D virtual reconstructions (top right, bottom right, and bottom left) of the patient's anatomy (red) and virtual donor implanted (green). The technique could potentially enable "virtual transplantations," allowing clinicians to model a particular donor (green) into a patient-specific recipient (red) and assess fit, along with the potential for mismatch-related morbidity. Image copyright: Cardiac 3D Print Lab, Phoenix Children's Hospital Heart Center.

Pretransplant image of patient C (top left) and 3D virtual reconstructions (top right, bottom right, and bottom left) of the patient's anatomy (red) and virtual donor implanted (green). The technique could potentially enable "virtual transplantations," allowing clinicians to model a particular donor (green) into a patient-specific recipient (red) and assess fit, along with the potential for mismatch-related morbidity. Image copyright: Cardiac 3D Print Lab, Phoenix Children's Hospital Heart Center.The method has the potential to reduce the number of well-functioning donor hearts that must be discarded, and it could also reduce the wait-list times and mortality associated with heart transplantation in pediatric patients, he said.

"The long-term goal is to do a multivariable setup with the healthy heart library with additional parameters, and then develop the technique from there," Plasencia said.

The ability to predict donor heart volume will improve as the library continues to grow, Plasencia said in an AHA statement. In addition, analyzing future cases with 3D matching will help the researchers predict the true upper and lower limits of acceptable donor size.

"This may allow more effective organ allocation on a national scale and minimize the number of otherwise acceptable organs that are ultimately discarded," he added.