The idea of printing human tissues and organs for implantation is not the stuff of science fiction anymore. It is a real prospect that will open new frontiers in medicine in less than a decade, delegates were told at this week's Arab Health congress in Dubai, United Arab Emirates.

The progress made already has been astonishing with many new breakthroughs reported regularly in the media such as the successful implantation into animals of sections of bone, muscle, and cartilage by the medical team at Wake Forest Baptist Medical Center in North Carolina, U.S., which could eventually pave the way for similar implantations in the human body.

Three-dimensional printing has come under close scrutiny at this week's Arab Health meeting. All images courtesy of Arab Health.

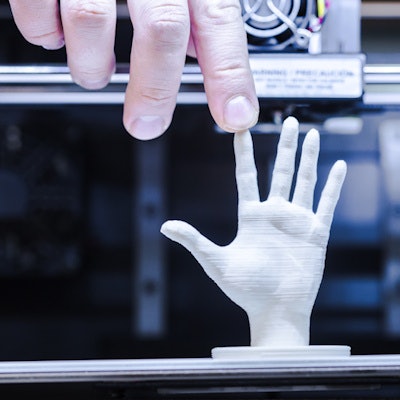

Three-dimensional printing has come under close scrutiny at this week's Arab Health meeting. All images courtesy of Arab Health.Swedish company Cellink is at the forefront of bioprinting, and at the moment grows cartilage and skin cells for testing drugs and cosmetics, but the company has bigger ambitions for the future and wants to produce organs for human implantation using bio-ink, which can be mixed with human cells and then 3D printed. The technology is pricey -- bio-inks can cost between $9 U.S. (7.26 euros) and $299 U.S. (241 euros) but the printers can cost anything up to $200,000 U.S. (161,336 euros). It would be a major medical revolution, but would not come without ethical concerns. Scrutiny and regulation must also be key components in this brave new world.

Last year saw the first U.K. National Health Service (NHS) use of 3D printing to enhance the precision and accuracy of robotic cancer surgery. After a 3D model of a patient's cancerous prostate was printed, surgeons from Guy's and St Thomas' hospital in London could see and feel the tumor in order to plan a precise robotic removal. Just one day after his surgery, the 65-year-old patient was able to get out of bed and go for a walk. Three-dimensional printing has been in use at Guy's and St. Thomas' for over a year. Last year, a team at the Guy's and St. Thomas' NHS Foundation Trust pioneered the use of 3D printing to aid a successful kidney transplant from an adult to a child.

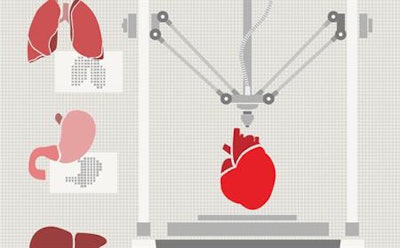

Bioprinting could be the answer to a global shortage of organs for transplants. Tim Lewis reported in the Guardian newspaper that the waiting time for a kidney transplant in the U.K. is more than two and a half years and there are similar long waits for liver, lungs, and other organs. He said the lack of transplant tissues is thought to be the leading cause of death in the U.S., but around one-third of deaths in the U.S. could be prevented or delayed by organ or engineered tissue transplants.

Take heart

In theory, the heart could be a good starting point for the fledgling bioprinting industry as it is one of the easiest organs to bioprint, given the fact it is fairly uncomplicated and well understood by scientists. It would be great news for the estimated 3,500 people in Europe who have waited more than two years for a new heart. The main thing holding developers back is the difficulty in creating blood vessels through bioprinting. Such is the challenge and desire for a breakthrough that NASA is offering a $500,000 U.S. (403,125 euros) prize in its Vascular Tissue Challenge.

The heart could be a good starting point for the bioprinting industry.

The heart could be a good starting point for the bioprinting industry.In a recent TED Talk, Carsten Engel, a biomedical engineer, said the major benefit of 3D printing is the ability to customize a product that is patient specific. "We can already see the impact. For example, 96% of all hearing aids worldwide are produced by 3D printing technology custom-produced for the patient's ear."

He added: "3D printing has also enabled a reduction in surgery time from 97 to 23 hours, which is amazing. This technology can bring a solution where there is no other solution. For example, an elderly patient with bone cancer had her entire jaw recreated in order to provide a solution for the surgeon. It was a patient-specific implant that matched exactly the function and weight of the previous jaw.

"This is where we are heading," he said. "We can print with metals, ceramics, and biodegradable materials; 3D printing is a powerful tool. It enables surgeons to rehearse, to pick the correct instruments and procedure to operate on the patient. It can save lives and bring a solution where there isn't one. It can go a bit further as well. Bioprinting can use stem cells from the patient and combine them with growth factors and construct them on a biodegradable scaffold in order to recreate organs."

The ethical debate

The main thrust of the disquiet surrounding the technology is about the quality of the implants and the allegation that humans will be able to "play god" with patients. However, researcher Dr. Gill Haddow at Edinburgh University's Science, Technology, and Innovation Studies Department claims there are already things like genetics that allow humans to play god and that bioprinting allows people to make small parts of the body to use for vital medical applications.

Engel also has his concerns. "It could be good news for heavy drinkers and smokers who can drink and smoke endlessly without thinking about the consequences and live on for a couple of hundred years, but is this the message we want to give through this technology? Or do we use it for specific cases such as saving the lives of babies and children? The real question for me though is just how far can we go?"

The 3D Medical Printing Conference at Arab Health, now continuing medical education (CME) accredited, took place on 29 to 30 January and provided a global perspective on the key challenges involved in the implementation of medical 3D printing practices in a variety of settings. The reality of the technology was discussed, offering an accurate view on the state of research and when anticipated emerging technologies such as bioprinting will be available. Regional and international case studies from a range of clinical specialties were presented, highlighting how it is revolutionizing healthcare from greater accuracy in surgical planning to improving efficiency through shorter surgical times.

Editor's note: This article originally appeared in the opening edition of the Arab Health 2018 daily newspaper, published on 29 January.