Which components of hospital 3D printing will you focus on to track, measure, and analyze its clinical value? This article details 12 potential value-capture areas clinicians may opt to prioritize as they commence or expand their hospital 3D printing services.

If you are in the initial planning stages of your start-up 3D printing service, now is an excellent time to build a clear path to value capture into your plans. If your service is already operational, with identifying and securing additional funding on the horizon, having a clear path to value capture is crucial.

3D printing value capture

Value capture can be defined as a means of quantifying the value added to patient care, the dollars saved by reducing operating time or cost, or the improved communication between the patient and the physician. It can also be defined as reduced training time and the lifetime knowledge accumulated by physicians utilizing surgical simulation with 3D-printed models.

For those who use 3D printing in clinical practice, the value to them is easily recognized by the utility of the models. However, because the process is generally not reimbursable, it is imperative to demonstrate the value to administrators.

There are numerous examples in the literature citing specific, measureable value capture as a direct result of patient-specific 3D-printed models, including the following:

- Increased surgeon confidence. Valverde et al found that "96% of cardiac surgeons agree or strongly agree that 3D-printed models provided better understanding of morphology and improved planning."1

- Enhanced understanding. "Using a 3D printing model changed the planned surgical approach in 10 out of 10 cases of complex renal masses," Wake et al reported.2

- Surgeon perception of improved patient care. Matsumoto et al found "19 tumor surgeons averaging seven cases using a 3D-printed model. Approximately 82% agreed that a model was 'very likely' to improve surgical outcomes."3

- Reduced operating room time. "For plastic surgery cases, a model resulted in time savings of 31.3 minutes and estimated cost savings of $1,036 per case," Rogers-Vizena et al wrote.4

- Case preparedness. "Perception of case preparedness was significantly improved (p < 0.5) after review of the 3D tractography model," Konakondla et al reported.5

Defining the 12 areas

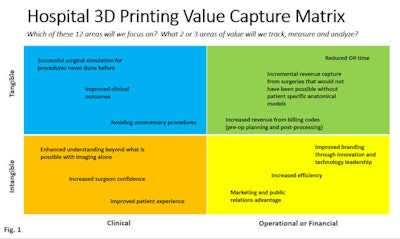

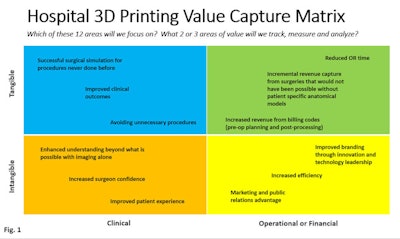

The figure below identifies 12 areas of potential value capture in four distinct quadrants: tangible -- clinical (blue), intangible -- clinical (orange), tangible -- operational/financial (green), and intangible -- operational/financial (yellow).

Image courtesy of Edward Stefanowicz and Bill O'Connell.

Each quadrant contains three potential areas of value, which may be captured as a direct result of implementing a hospital 3D printing service.

Tangible -- clinical

- Successful surgical simulation for procedures never done before: How many? Over what time period? How can we design a feedback form for practicing/requesting surgeons?

- Improved clinical outcomes: Which procedures, specifically? How will we define "improved clinical outcomes"? How many procedures? Over what time period?

- Avoiding unnecessary procedures: Which procedures, specifically? How many? Over what time period?

Intangible -- clinical

- Enhanced understanding beyond what is possible with imaging alone: How will we define and measure this? For which procedures, specifically? How many? Over what time period?

- Increased surgeon confidence: How will we define and measure this? For which procedures, specifically? How many? Over what time period?

- Improved patient experience: How we define and measure this? For which procedures, specifically? How many? Over what time period?

Tangible -- operational or financial

- Reduced time in the operating room: How will we define and measure this? For which procedures, specifically? How many? Over what time period?

- Incremental revenue capture from surgeries that would not have been possible without patient-specific anatomical models: How will we define and measure this? For which procedures, specifically? How many? Over what time period?

- Increased revenue from billing codes (pre-op planning and postprocessing): How will we define and measure this? For which procedures, specifically? How many? Over what time period?

Intangible -- operational or financial

- Improved branding through innovation and technology leadership: How will we define and measure this?

- Increased process efficiency: How will we define and measure this?

- Marketing and public relations advantage: How will we define and measure this?

The quadrants and areas they contain are not intended to be exhaustive, but rather a starter set of ideas for consideration. You and your team may identify other areas of potential value capture more relevant to and in alignment with your organization's strategic initiatives.

Rather than attempting to focus on all 12 areas, we strongly recommend choosing one to three areas that you and your team believe are most achievable and relevant to your site-specific environment.

Which areas to focus on?

You may consider forming a 3D printing steering committee at your institution. It could be a very small group to start, perhaps involving your department director, the medical director of the 3D printing lab, a senior member of the administration, and a few key referring clinicians.

The size and makeup of your committee will depend greatly on the size of your organization and the interest in a 3D printing service at your facility. You may consider advising the printing committee for the hospital 3D printing lab to capture value-adding data that are highly relevant, realistic, and achievable for your institution's unique environment. This may be in alignment with your organization's vision, mission, values, and strategic plan.

We recommend that you provide an opportunity for your committee to discuss and ultimately select a short list of key value-capture areas to focus on for the coming year.

Conclusion

Every hospital-based 3D printing lab begins with good intentions, but because of significant start-up costs and lack of reimbursement, it will be difficult to show a return on investment. By building a clear path to capture value in your business plan, you can prepare to defend and justify continued funding for your 3D printing lab operation.

Of the starter set of 12 potential areas of value capture, we strongly encourage identifying two or three to track, measure, analyze, and report on. However, it is better to pick just one area to intently focus on, plan for, and successfully implement than to pick five or six but not fully implement them because available resources were stretched too thin.

Consider preparing a one- or two-sentence value capture statement, or elevator pitch, that describes the single most important reason why you are implementing a 3D printing program and the measureable impact your team seeks to achieve. This will help communicate the value of your 3D printing service to senior administrators, board members, and other interested parties who may influence, or control, funding decisions.

Lastly, create a simple project plan and hold weekly conference calls with your team to track your lab's progress and your value capture initiative. Record the results and report them to your executive sponsor each month. Be proactive and capture the value-adding areas that 3D printing generates, both tangible and intangible. Funding for your department may be determined by how diligently you value capture!

References

- Valverde I, Gomez-Ciriza G, Hussain T, et al. Three-dimensional printed models for surgical planning of complex congenital heart defects: an international multicentre study. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2017;52(6):1139-1148.

- Wake N, Rude T, Kang S, et al. 3D printed renal cancer models derived from MRI data: application in presurgical planning. Abdom Radiol. 2017;42(5):1501-1509.

- Matsumoto J, Morris J, Rose P. 3-dimensional printed anatomical models as planning aids in complex oncology surgery. JAMA Oncol. 2016;2(9):1121-1122.

- Rogers-Vizena C, Sporn S, Daniels K, Padwa B, Weinstock P. Cost-benefit analysis of three-dimensional craniofacial models for midfacial distraction: a pilot study. Cleft Palate Craniofac J. 2017;54(5):612-617.

- Konakondla S, Brimley CJ, Sublett JM, et al. Multimodality 3D superposition and automated whole brain tractography: comprehensive printing of the functional brain. Cureus. 2017;9(9):e1731.

Edward Stefanowicz is an MRI and radiologic technologist and operations director for the Neuroscience Institute at Geisinger Medical Center. He is also team leader of the 3D imaging lab at Geisinger Health System, which provides 3D printing services such as postprocessing of CT and MRI scans as well as creating patient-specific 3D-printed anatomical models.

Bill O'Connell is the North American regional sales director for 3D printing firm Materialise. He works with leading physicians and hospital administrators to help them develop and deploy their 3D printing strategy.

The comments and observations expressed are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the opinions of AuntMinnie.com.